Technocracy and the Space Age

In this update:

Technocracy and the Space Age

Links and tweets

Technocracy and the Space Age

Earlier I proposed a hypothesis that the 1930s–60s in the US were characterized by the attempt to achieve progress through top-down control by a technical elite.

The 1997 preface to Walter McDougall’s Pulitzer-winning The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age adds some evidence for this. McDougall laments NASA’s failed promises and the lost potential of space technology, and he ties this in to the broader theme of failures of centralized federal programs:

From today’s vantage point the Space Age may well be defined as an era of hubris. Not only did it become obvious in the 1960s and 1970s that “planned invention of the future” through federal mobilization of technology and brainpower was failing everywhere from Vietnam to our inner cities, but that it even failed in the arena for which it had seemed ideally suited: space technology.

What were the promises?

In the years following Sputnik I, experts assured congressional committees that by the year 2000 the United States and the Soviet Union would have lunar colonies and laser-armed spaceships in orbit. The film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) depicted Hilton hotels on the Moon and a manned mission to Jupiter (January 12, 1992, was the supercomputer Hal’s birthday in the film). In the late 1960s, NASA promoters imagined reusable spacecraft ascending and descending like angels on Jacob’s ladder, permanent space stations, and human missions to Mars—all within a decade. In the 1970s, visionaries looked forward to using the Space Shuttle to launch into orbit huge solar panels that would beam unlimited, nonpolluting energy to earth, hydroponic farming in space to feed the earth’s exploding population, and systems to control terrestrial weather for civilian or military purposes. In the 1980s, the space station project was revived (to be completed again “within a decade”), the Strategic Defense Initiative was to put laser-beam weapons in orbit to shoot down missiles and make nuclear weapons obsolete, and the space telescope was to unlock the last secrets of the universe. By 1990, a manned mission to Mars by the year 2010 was on the president’s wish list, and research had begun on an aerospace plane (the “Orient Express”) to whisk passengers across the Pacific in an hour and land like an airplane in Asia.

None of it came to pass.

McDougall describes the decline of NASA’s budget and the loss of its talent and “institutional charisma.” The Nixon administration “chose to throw away the incomparable Saturn/Apollo systems and start from scratch on a reusable launch system,” which became the Space Shuttle. But:

Given the political and economic pressures of the 1970s, the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations also insisted that the Shuttle be built on a shoestring. So NASA dutifully compromised the “fully reusable” feature, made other design changes to accommodate Air Force requirements, sharply constricted the Shuttle’s performance envelope, and yet persisted in exaggerating its capabilities and underestimating its cost. When the spacecraft finally flew in 1981, it was late, well over budget, full of bugs, and able to fly just four to six missions per year, not the twenty four promised. So, far from cutting the cost per pound of launching payloads into orbit “by a factor of ten,” the Shuttle increased the cost several times over that of the old Saturn 5 rocket.

He also points out that the USSR, “the regime that made technocracy its founding principle,” did even worse: “Not only did Soviet space programs keep even fewer promises than the American programs, but the Soviet Union itself crashed and burned.” (I have to think that this was another major factor in the decline of technocracy, in addition to the US-centric factors I mentioned in my earlier essay, such as Vietnam, Watergate, and the oil shocks.)

He adds:

Forty years into the Space Age one fact remains painfully clear: the biggest reason why so few promises have been fulfilled is that we are still blasting people and things into orbit with updated versions of 1940s German technology. … The way to restart the Space Age is to discover some new principle that makes spaceflight genuinely cheap, safe, and routine. Under present circumstances, that breakthrough is more likely to be made by some twenty four-year-old visionary working in a garage in Los Angeles than by the engineers, laboring under political constraints in the laboratories of NASA or Rockwell.

SpaceX was founded five years after this was written.

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/technocracy-and-the-space-age

Links and tweets

Opportunities

Arcadia Science launches an Entrepreneur-in-Residence (EIR) program (thread from @ArcadiaScience)

The Longevity Prize goes to “outstanding progress in longevity research” (announcement from @allisondman)

Helion Energy is hiring. “Clean, continuous energy for 1 cent per kilowatt-hour”

Nicole Ruiz is making a list of opportunities in frontier tech (@nwilliams030)

And don’t forget that The Roots of Progress is seeking a CEO! Thanks to Max Roser and Virginia Postrel, among others, for signal-boosting

Announcements

UK’s new Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) adds Matt Clifford as chairman and Ilan Gur as CEO. Gur will step down as CEO of Activate. See also threads from @matthewclifford and @ilangur. Congrats to all!

Boom announces the new design for its supersonic airplane, Overture

Other links

Works in Progress Issue #8 with articles from Stewart Brand, Jason Collins, and more

Joel Mokyr reviews Koyama & Rubin’s How the World Became Rich

Lant Pritchett on the difference between anti-poverty programs and poverty reduction. To paraphrase Rutherford, all poverty reduction is either economic growth or stamp collecting

The first images from the JWST look amazing. See also this comparison with Hubble

“Large changes in productivity are always widely shared” (Bryan Caplan)

Can exponential growth occur if productivity is the best draw from a probability distribution? A talk by Chad Jones (fairly technical)

Potential for a vaccine against a broad category of SARS-like coronaviruses (in Science; see also the announcement from Wellcome Leap which funded this)

A DNA origami rotary ratchet motor (Nature, h/t @s_r_constantin)

Threads

Charles Mann calls for industrial literacy in high school (@CharlesCMann). See my take on “industrial literacy” and the high school progress course I created

Many waste byproducts were developed in Britain during the Industrial Revolution (@VincentGeloso). See also: In capitalism they use every part of the animal

“Reclosers” on electrical utility poles (@HillhouseGrady)

Some potential use-cases for crypto (@SBF_FTX)

Software + web tech recapitulating the institutions and ideals of the Enlightenment (@arbesman)

It turns out, nobody ever wanted to work (@paulisci)

Quotes

Maps were originally created through the blood, sweat and tears of field agents

Modern facilities added ~3x to the consumer value of housing

Queries

Why is hating humanity acceptable? (@CineraVerinia)

Why doesn’t washing hands create hand-washing resistant bacteria? (@_brianpotter)

What’s the best CO2 monitor? (@_brianpotter)

Tweets & retweets

Request for blog: the history of social change, and lessons for modern movements

Terraform Industries can convert H2 and CO2 into natural gas (@TerraformIndies)

RIP Dee Hock, creator of Visa (@patrickc)

Montessori on the need to teach “the highest discoveries” of science (@mbateman)

There’s an Industrial Revolution board game set in 18th-c. Lancashire (@dkedrosky)

“The Roman Empire was not run out of offices” (Marc Andreessen on Conversations with Tyler)

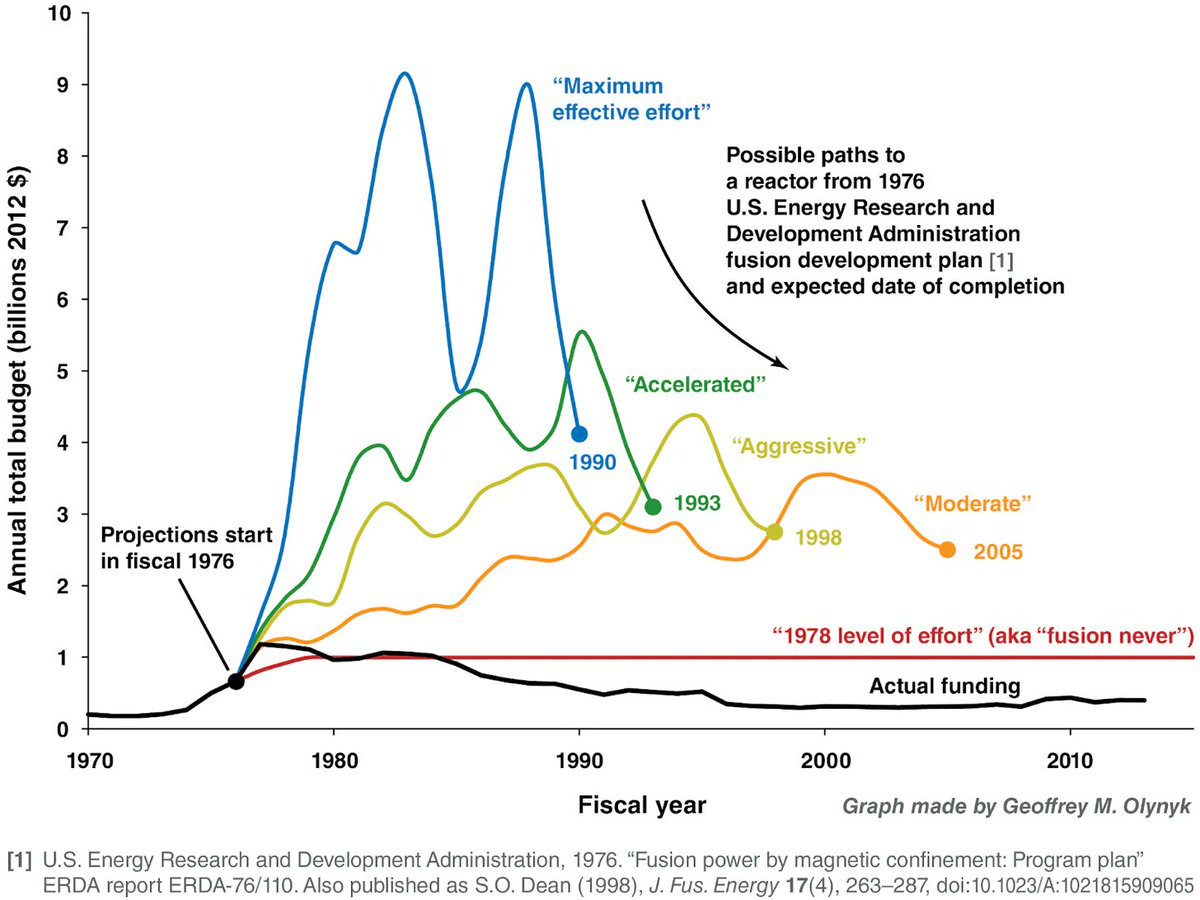

The reason we don’t have fusion is we never decided it was a priority (@tobi)