Accelerating science through evolvable institutions

If we want to see our scientific institutions improve, we need to make sure they can evolve

An end-of-year appeal

The Roots of Progress Fellowship was a great success, and we are excited to expand the program in 2024! To do this, we have a goal of raising $500k by the end of the year. View our full fundraising pitch here.

We’re more than 20% there, and we’d make it if half the people on this list would:

If you’re considering a larger gift, see info here or get in touch.

In this update:

Full text below, or click any link above to jump to an individual post on the blog. If this digest gets cut off in your email, click the headline above to read it on the web.

Accelerating science through evolvable institutions

This is the written version of a talk presented to the Santa Fe Institute at a working group on “Accelerating Science.”

We’re here to discuss “accelerating science.” I like to start on topics like this by taking the historical view: When (if ever) has science accelerated in the past? Is it still accelerating now? And what can we learn from that?

I’ll submit that science, and more generally human knowledge, has been accelerating, for basically all of human history. I can’t prove this yet (and I’m only about 90% sure of it myself), but let me appeal to your intuition:

Behaviorally modern humans are over 50,000 years old

Writing is only about 5,000 years old, so for more than 90% of the human timeline, we could only accumulate as much knowledge as could fit in an oral tradition

In the ancient and medieval world, we had only a handful of sciences: astronomy, geometry, some number theory, some optics, some anatomy

In the centuries after the Scientific Revolution (roughly 1500s–1700s), we got the heliocentric theory, the laws of motion, the theory of gravitation, the beginnings of chemistry, the discovery of the cell, better theories of optics

In the 1800s, things really got going, and we got electromagnetism, the atomic theory, the theory of evolution, the germ theory

In the 1900s things continued strong, with nuclear physics, quantum physics, relativity, molecular biology, and genetics

I’m leaving aside the question of whether science has slowed down since ~1950 or so, which I don’t have a strong opinion on. Even if it has, that’s mostly a minor, recent blip in the overall pattern of acceleration across the broad sweep of history. (Or, you know, the beginning of a historically unprecedented reversal and decline. One or the other.)

Part of the reason I’m pretty convinced of this accelerating pattern is that it’s not just science that is accelerating: pretty much all measures of human advancement show the same trend, including world GDP and world population.

What drives acceleration in science? Many factors, including:

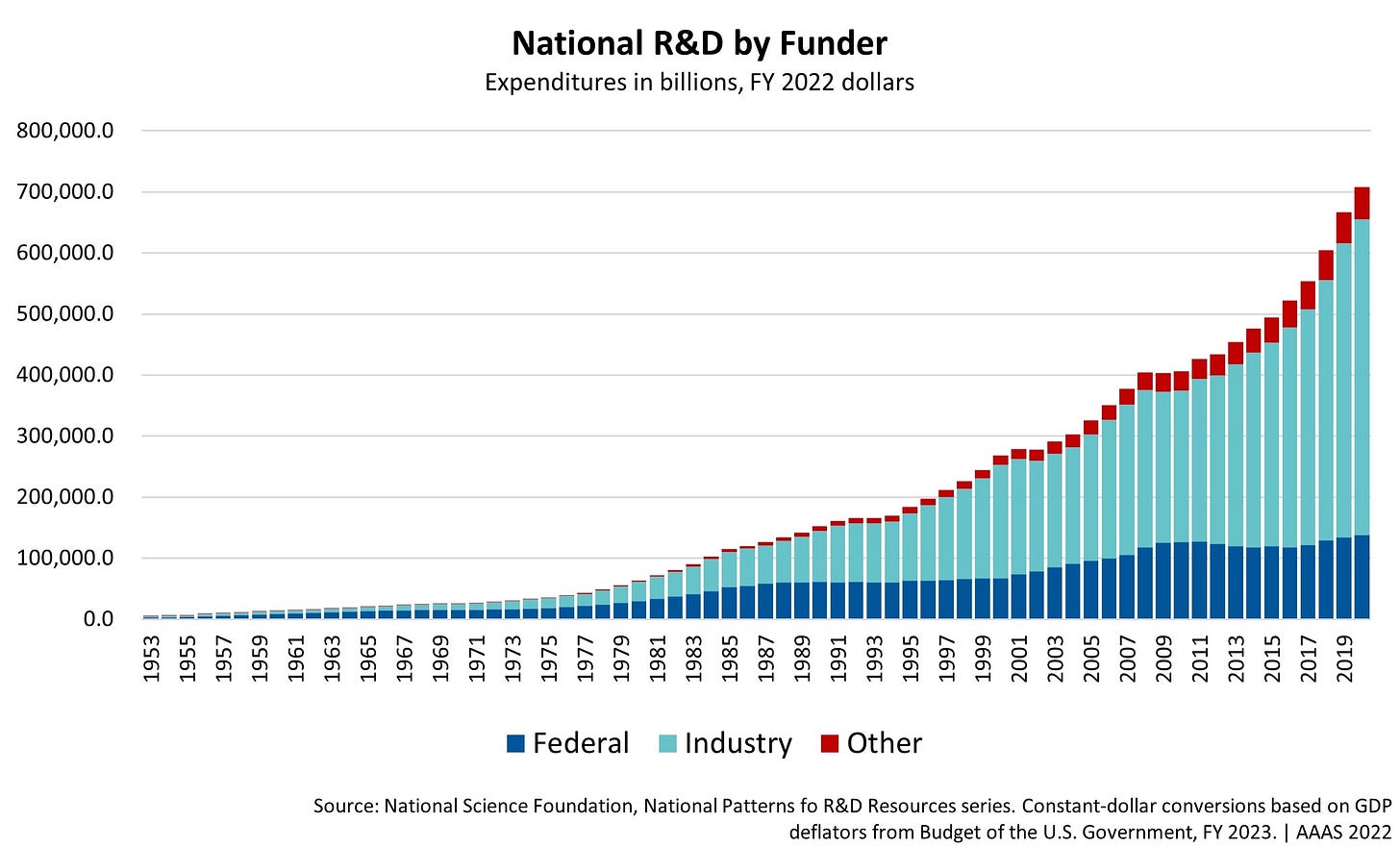

Funding. Once, scientists had to seek patronage, or be independently wealthy. Now there is grant money available, and the total amount of funding has increased significantly in the last several decades:

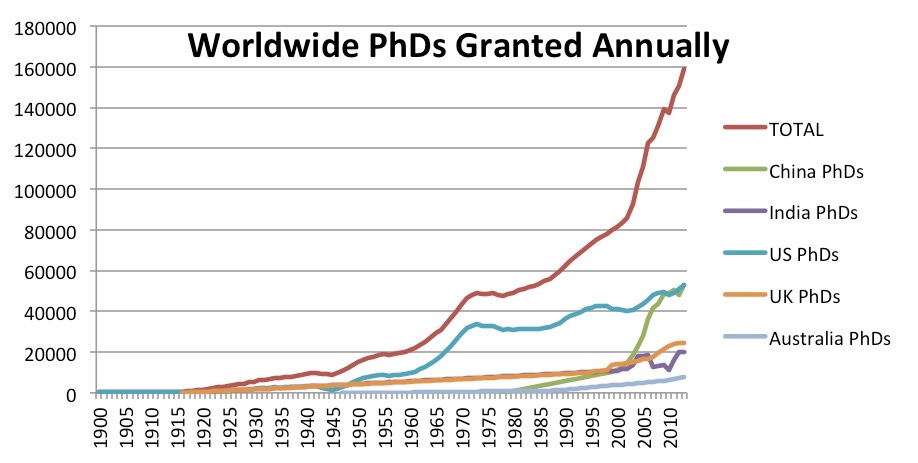

People. More scientists (all else being equal) means science moves faster, and the number of scientists has grown dramatically, both because of overall population growth and because of a greater portion of the workforce going into research. In Science Since Babylon, Derek J. de Solla Price suggested that “Some 80 to 90 percent of all scientists that have ever been, are alive now,” and this is probably still true:

Instruments. Better tools means we can do more and better science. Galileo had a simple telescope; now we have JWST and LIGO.

Computation. More computing power means more and better ways to process data.

Communication. The faster and better that ideas can spread, the more efficient and effective scientific communication can be. The scientific journal was invented only after the printing press; the Internet enabled preprint servers such as arXiv.

Method. Better methods make for better science, from Baconian empiricism to Koch’s postulates to the RCT (and really, all of statistics).

Institutions. Laboratories, universities, journals, funding agencies, etc. all make up an ecosystem that enables modern science.

Social status. The more science carries respect and prestige, the more people and money flow into it.

Now, if we want to ask whether science will continue to accelerate, we could think about which of these driving factors will continue to grow. I would suggest that:

Funding for science will continue to grow as long as the world economy does

Instruments, computation, and communication will continue to improve along with technology in general

I see no reason why method should not continue to improve, as part of science itself

The social status of science seems fairly strong: it is a respected and prestigious institution that receives some of society’s top honors

In the long run, we may run out of people to continue to grow the base of researchers, if world population levels off as it is projected to do, and that is a potential concern, but not my focus today.

The biggest red flag is with our institutions of science. Institutions affect all the other factors, especially the management of money and talent. And today, many in the metascience community have concerns about our institutions. Common criticisms include:

Speed. It can easily take 12–18 months to get a grant (if you’re lucky)

Overhead. Researchers typically spend 30–50% of their time on grants

Patience. Researchers feel they need to show results regularly and can’t pursue a path that might take many years to get to an outcome

Risk tolerance. Grant funding favors conservative, incremental proposals rather than bold, “high-risk, high-reward” programs (despite efforts to the contrary)

Consensus. A field can converge on a hypothesis and prune alternate branches of study too quickly

Researcher age. The trend over time is for grant money to go to older, more established researchers

Freedom. Scientists lack the freedom to direct their research fully autonomously; grant funding has too many strings attached

Now, as a former tech founder, I can’t help but notice that most of these problems seem much alleviated in the world of for-profit VC funding. Raising VC money is relatively quick (typically a round comes together in a few months rather than a year or more). As a founder/CEO, I spent about 10–15% of my time fundraising, not 30–50%. VCs make bold bets, actively seek contrarian positions, and back young upstarts. They mostly give founders autonomy, perhaps taking a board seat for governance, and only firing the CEO for very bad performance. (The only concern listed above that startup founders might also complain about is patience: if your money runs out, you’d better have progress to show for it, or you’re going to have a bad time raising the next round.)

I don’t think the VC world does better on these points because VCs are smarter, wiser, or better people than science funders—they’re not. Rather, VCs:

Compete for deals (and really don’t want to miss good deals)

Succeed or fail in the long run based on the performance of their portfolio

See those outcomes within a matter of ~5–10 years

In short, VCs are subject to evolutionary pressure. They can’t get stuck in obviously bad equilibria because if they do they will get out-competed and lose market power.

The proof of this is that VC has evolved over the decades—mostly in the direction of better treatment for founders. For instance, there has been a long-term trend towards higher valuations at earlier stages, which ultimately means lower dilution and a shift in power from VCs to founders: it used to be common for founders to give up half or more of their company in the first round of funding; last I checked that was more like 20% or less. VCs didn’t always fund young techies right out of college; there was a time when they tended to favor more experienced CEOs, perhaps with an MBA. They didn’t always support founder-led companies; once it was common for founders to get booted after the first few years and replaced with a professional CEO (when A16Z launched in 2009 they made a big deal out of how they were not going to do that).

So I think if we want to see our scientific institutions improve, we need to think about how they can evolve.

How evolvable are our scientific institutions? Not very. Most scientific organizations today are departments of university or government. Much as I respect universities and government, I think anyone would have to admit that they are some of our more slow-moving institutions. (Universities in particular are extremely resilient and resistant to change: Oxford and Cambridge, for instance, date from the Middle Ages and have survived the rise and fall of empires to reach the present day fairly intact.)

The challenges to the evolvability of scientific funding institutions are the inverse of what makes VC evolvable:

They tend to lack competition, especially centralized federal agencies such as NIH and NSF

They lack any real feedback loop in which a funder’s resources are determined somehow by past judgment and the success of their portfolio (Michael Nielsen has repeatedly pointed out that failures of funding from “Einstein did his best work as a patent clerk” to “Katalin Karikó was denied grants and tenure before she won the Nobel prize” don’t seem to even spark processes of reflection within the relevant institutions)

They face long cycle times to learn the true impact of their work, which might not be apparent for 20–30 years

How might we improve evolvability of science funding? We should think about how we can improve these factors. I don’t have great ideas, but I’ll throw some half-baked ones out there to start the conversation:

How might we increase competition in science funding? We could increase the role of philanthropy. In the US, we could shift federal funding to the state level, creating fifty funders instead of one. (State agricultural experiment stations are a successful example of this, and competition among these stations was key to hybrid corn research, one of the biggest successes of 20th-century agricultural science.) At the international level, we could support more open immigration for scientists.

How might we create better feedback loops? This is tough because we need some way to measure outcomes. One way to do that would be to shift funding away from prospective grants and more towards a wide variety of retrospective prizes, at all levels. If this “economy” were sufficiently large and robust, these outcomes could be financialized in order to create a dynamic, competitive funding ecosystem, with the right level of risk-taking and patience, the right balance of seasoned veterans vs. young mavericks, etc. (Certificates of impact, such as hypercerts, could be part of this solution.)

How might we solve long feedback cycles? I don’t know. If we can’t shorten the cycles, maybe we need to lengthen the careers of funders, so they can at least learn from a few cycles—a potential benefit of longevity technology. Or, maybe we need a science funder that can learn extremely fast, can consume large amounts of historical information on research programs and their eventual outcomes, never forgets its experience, and never retires or dies—of course, I’m thinking of AI. There’s been a lot of talk of AI to support, augment, or replace scientific researchers themselves, but maybe the biggest opportunity for AI in science is on the funding and management side.

I doubt that grant-making institutions will shift themselves very far in this direction: they would have to voluntarily subject themselves to competition, enforce accountability, and admit mistakes, which is rare. (Just look at the institutions now taking credit for Karikó’s Nobel win when they did so little to support her.) If it’s hard for institutions to evolve, it’s even harder for them to meta-evolve.

But maybe the funders behind the funders, those who supply the budgets to the grant-makers, could begin to split up their funds among multiple institutions, to require performance metrics, or simply to shift to the retrospective model indicated above. That could supply the needed evolutionary pressure.

Original post: rootsofprogress.org/accelerating-science-through-evolvable-institutions

Links digest, 2023-12-15: Vitalik on d/acc, $100M+ in prizes, and more

Job openings

Economic Innovation Group is looking for a spring research intern (via ROP fellow @cojobrien)

Future House (AI for bio) hiring for their Assessment Team. “We want Future House to be the world leader for evaluating the scientific abilities of AI systems” (@SGRodriques)

Convergent Research hiring Chief of Staff to Adam Marblestone (via @AGamick)

Anthropic hiring senior-to-staff-level security engineers (via @JasonDClinton)

Prizes

$101M XPRIZE “aims to extend human healthspan by a decade” (by ROP fellow @RaianyRomanni)

$10M AI Mathematical Olympiad Prize from @AlexanderGerko (via @natfriedman)

The Lovelace Future Scientific Institutions Essay Prize: “£1500 each for 3-5 essays that offer bold, transformative visions for new scientific institutions” (via @BetterScienceUK)

Other opportunities

Economics of Ideas, Science, and Innovation Online PhD Short Course from IFP (via @heidilwilliams_). Also, many of the same people are doing an Innovation Research Boot Camp in Cambridge, MA, July 12–18 (also via @heidilwilliams_)

Astera wants to fund ~10 “icebox experiments… for start-ups that want to publish their science as/after they ramp down” (@seemaychou, application form here)

RIP, Charlie Munger

Munger giving the USC Law Commencement 2007 (via @garrytan):

The last idea that I want to give you, as you go out into a profession that frequently puts a lot of procedure, and a lot of precautions, and a lot of mumbo-jumbo into what it does, this is not the highest form which civilization can reach.

The highest form that civilization can reach is a seamless web of deserved trust. Not much procedure, just totally reliable people correctly trusting one another.

That’s the way an operating room works at the Mayo Clinic. If a bunch of lawyers were to introduce a lot of process, the patients would all die.

So never forget, when you’re a lawyer, that you may be rewarded for selling this stuff, but you don’t have to buy it. In your own life, what you want is a seamless web of deserved trust. And if your proposed marriage contract has forty-seven pages, my suggestion is you not enter.

I heard the news from @_TamaraWinter; coincidentally, Stripe Press just republished Poor Charlie’s Almanack.

Bio announcements

FDA agrees Loyal’s data supports reasonable expectation of effectiveness for large dog lifespan extension. See thread from founder @celinehalioua. Investor @LauraDeming calls it “the most important milestone in the history of longevity biotech” (thread); @elidourado says “EPIC”

Orchid announces whole genome embryo reports (via @noor_siddiqui_)

More on the first ever approved CRISPR therapy, for sickle-cell anemia, which was mentioned in the last digest (via @s_r_constantin)

AI announcements

Pika 1.0, an idea-to-video platform (via @pika_labs). We are at the dawn of a golden age of creativity: 100x as many people will be able to make their vision into reality, new blockbusters will come out of nowhere, and everyone will benefit. (And we will escape the endless sequels and franchise reboots.) “When digital filmmaking became viable in the 90s, I expected a boom in independent cinema that never materialized…. AI may finally deliver on this promise, as one creative person can prompt videos that previously would take the collaboration of hundreds of people to capture. The next 10 years of cinema could be weird and wonderful” (@ryrzny)

Pancreatic cancer detection with artificial intelligence (PANDA) “can detect and classify pancreatic lesions with high accuracy via non-contrast CT”; it “outperforms the mean radiologist” (via @DKThomp)

Google announces Gemini, “a family of multimodal models that demonstrate really strong capabilities across the image, audio, video, and text domains” (@JeffDean). There was a very impressive demo going around, but it turned out to be, er, enhanced (some would say “entirely fake”)

Claude 2.1: “200K token context window, a 2x decrease in hallucination rates, system prompts, tool use, and updated pricing” (via @AnthropicAI)

PartyRock, from AWS: describe an app and AI creates it for you

Bio ∩ AI announcements

Future House announces WikiCrow, which “generates Wikipedia style articles on scientific topics by summarizing full-text scientific articles” (via @SGRodriques). “As a demo, we are releasing a cited technical summary for every gene in the human genome that previously lacked a Wikipedia article: 15,616 in all.” They are hiring, see link above

Energy/climate announcements

On Dec 2, “representatives from 20 countries signed a declaration establishing a goal of TRIPLING global nuclear energy production by 2050” (@Atomicrod)

Plans for Nuclear-Powered 24,000 TEU Containership Unveiled in China (via @whatisnuclear)

Frontier makes an advance market commitment of $57M in carbon removal from Lithos Carbon. “Lithos will deliver 154,240 tons of CDR in the next 2-6 years”(via @heyjudka)

UK news

“The UK is going to try to create a pathway for individually customised medicines” (@natashaloder, via @benedictcooney)

Independent review of university spin-out companies finds “universities should take much smaller equity stakes in academic spinouts” (@Sam_Dumitriu). See thread from @nathanbenaich who has been advocating for this (also comments from @josephflaherty and @kulesatony)

British Library hit by ransomware: “The level of cultural vandalism here is truly shocking…. Like the digital version of the burning of the Library of Alexandria,” says (@antonhowes)

Risk, safety, and tech

Vitalik Buterin’s “current perspective on the recent debates around techno-optimism, AI risks, and ways to avoid extreme centralization in the 21st century.” (via @VitalikButerin). He proposes “d/acc”, where the “d” can stand for “many things; particularly, defense, decentralization, democracy and differential,” and he suggests this message to AI developers: “you should build, and build profitable things, but be much more selective and intentional in making sure you are building things that help you and humanity thrive”

Michael Nielsen on “wise accelerationism”. “Will a sufficiently deep understanding of nature make it almost trivial for an individual to make catastrophic, ungovernable technologies?” If so, “what institutional ideas or governance mechanisms can we use to stay out of this dangerous realm?”

“We need some serious people who are also builders and not decelerationists. These issues are too crucial to be left to vibes-based shitposters” (me). And: “Like Jason, I like e/acc vibes, but agree they are not enough. Build the future with evidence, careful thought, well-roundedness, courage, earnestness, creativity, strength, love of life, curiosity, vulnerability, nuance, hard work, and a can-do spirit” (@elidourado)

“I’m neither an accelerationist nor a decel when it comes to AI / AGI. This is technology we absolutely must build, and we’ll build it regardless. But I hope thoughtfully, not carelessly. Reducing a debate to a memetic tribal saying to tweet or add to bio is fun—but not a strategy” (@rsg). Related: “Threading the needle between being an AI panglossian and being an AI doomer is hard sometimes. Social dynamics often force people to identify with a simple ideological camp, but reality doesn’t always fit neatly into a single camp” (@MatthewJBar)

“One difference between the EA and progress studies communities: ‘Progress is inevitable and maybe even happening too fast, and maximum efforts against it can only slow it by a bit (which might not be enough)’ vs. ‘Progress can be stopped, and without active efforts to protect it, it will probably happen too slowly’” (me)

“A personal take on how Sam’s done as CEO with respect to AI safety. Far from perfect. But way better than most alternatives and a huge margin better than the next-most-likely outcomes” (thread from @jachiam0). I particularly appreciated this point: “When people ask me what safety is, my answer is always something along the lines of: ‘safety is a negotiation between stakeholders about acceptable risk.’ All parts of this are important. Safety is not a state; it’s a conversation, a negotiation”

“I take AI safety pretty seriously, but it really bothers me that some in the AI safety world don’t take the upsides of AGI seriously. Yes, we should try to avoid an AGI that wipes out humanity, but an AGI that could end death isn’t something to give up trying to develop ASAP” (@s8mb)

“There will almost certainly come a point (p=.999?) where an AI is developed that a) poses no threat to humanity civilization and b) is able to perform enough economically meaningful work to cause some humans to lose their jobs. At that point, there will be bootleggers and Baptists situation. Make-workers = bootleggers; Safetyists = Baptists. We have few social antibodies against this kind of alliance. I continue to worry we will never reap the economic benefits of AI. We need: decentralized and open source AI; freedom to compute; preemptive attacks on make-workism; a norm against restrictive forms of safetyism unless there is some kind of empirical evidence that danger is imminent” (@elidourado)

More thoughts from me

If no one is criticizing you, it’s not because your work is unimpeachable: it’s because you’re not doing/saying anything important, or you don’t have a significant audience. Any important work that gets attention will draw criticism (Threads, Twitter)

The tragedy is that bioethics ought to be a serious, interesting field. There are big, important questions that deserve deep thought. But bioethicists have made a mockery of the field by extreme hand-wringing and waffling over very easy questions (Twitter)

Podcasts

Dwarkesh interviews Dominic Cummings on “why Western governments are so dangerously broken, and how to fix them before an even more catastrophic crisis” (via @dwarkesh_sp)

Episode 7 of Age of Miracles: “What will the energy mix look like in 2050? We’re not nuclear maxis. We’re energy abundance and human flourishing maxis. Getting there is going to take a mix of nuclear, solar, wind (?), geothermal, hydro, fusion, and… fossil fuels. Yes, fossil fuels.” (@packyM). And episode 8 is focused on fusion (also via @packyM)

Video

1-hour general-audience introduction to Large Language Models: “non-technical intro, covers mental models for LLM inference, training, finetuning, the emerging LLM OS and LLM Security” (via @karpathy)

Papers

The rise of tea drinking in England had a significant impact on mortality during the Industrial Revolution (via @restatjournal, via @albrgr and @mattyglesias)

“Global poverty is commonly measured by counting the number of people whose consumption falls below a given threshold. This approach overlooks an enormous component of people’s economic well-being: public goods” (thread from @amorygethin based on this working paper)

Other articles and links

Test your understanding of some of the topics I’ve written about, using an AI chatbot that will quiz you on them. (It works better for topics like “Bessemer converter” than it does for “progress as a moral imperative”)

New Statecraft interview with a DARPA PM. “But what works about the ARPA model, and which parts can’t scale? How do you succeed as a DARPA PM?” (via @rSanti97)

“Deep tech is probably the best place to invest today” (by @lpolovets). Pure software/Internet businesses, as a category, are well into the flattening part of their S-curve. Investment (money, time, energy, and focus) shifting to other fields

Queries

Click through and answer if you can help:

“Who would want to work on [a startup to build open-source parametric CAD software] with @Spec__Tech?” (@Ben_Reinhardt)

“People who work in biotech: Would you pay for access to a new database of clinical-stage failures by target, and the reasons for failure (incl. metadata on phase, program milestones and dates, company, etc.)?” (ROP fellow @Atelfo)

“Is anyone working on an AI tool to do basic quality checks on scientific papers? Check for prereg; cross-check prereg outcomes with paper; check for appropriate power calc; check for appropriate stats; basic fraud checks” (@sguyenet)

“What’s the best answer to why more good universities aren’t being founded in the last 50 years? (e.g. the 1890s alone had Stanford, UChicago, & Caltech.)” (@nabeelqu) (My comment: “FWIW 1890s was a special time. US badly needed top tier research universities and did not have any. Europe outclassed them especially Germany. So there was an urgent need that we don’t have now”)

On not romanticizing the past

“We are so impossibly wealthy in the modern era” (@kendrictonn, commenting on the nail manufacturing link below). “All these things that used to be expensive enough to notice and care about. It’s dizzying when you start to think about it.” Good thread, read the whole thing

“In the Middle Ages ordinary people in Europe could not afford plates and the practice was to eat off yesterday’s stale bread, called a trencher. By the 14th century most people used wooden trenchers, and by the 17th century pewter (dangerous!) or earthenware plates” (@DavidDeutschOxf)

“Most modern architecture replaced misery, not beauty.” Good thread from @culturaltutor

“This Thanksgiving I am particularly thankful for the existence of centralised heating and hot water at one’s fingertips. Our hot water was temporarily discontinued due to a leakage, and it’s the best time to remember how good we have it compared to our ancestors!” (@RuxandraTeslo)

More social media

Breakthroughs of 2023 (thread from @g_leech_)

“Project Lyra explores the possibility of sending a spacecraft to chase ‘Oumuamua using an Earth gravity assist to reach Jupiter, which robs the craft of almost all its speed, causing it to drop to the Sun for an Oberth maneuver” (@tony873004, check out the trajectory visualization)

“Forming and extruding nails,” cool video from @MachinePix

Audio excerpt from Katalin Karikó interview: “How the sheer joy of doing science fed her resolve” (from a very good podcast I linked earlier)

“Let’s say you have a humanoid robot with AGI. How much power does the robot need on board to do continuous inference? What is a good power source that has appropriate density and portability?” (thread from @elidourado). See also related thread from Eli on “the energy requirements of an ‘intelligence explosion’ scenario,” with replies from @anderssandberg where he points to this paper

“Even though it feels like there are a million health metrics you can track through wearables etc, health is actually UNDER tracked. The average machine/software/etc has so many more available stats” (@auren quoting Sam Corcos)

“I think I’m changing my mind about prediction markets. Whether it’s the House Speaker drama, or the OpenAI story, I’ve noticed they’re definitely becoming part of my news consumption” (@TheStalwart)

ChatGPT explains a pretty subtle joke requiring both image recognition and understanding calculus

Politics and culture

Austin City Council votes to legalize 3 homes per lot. “Incredibly proud of the work our AURA volunteers and partners put in over the past six months to make this win possible. Austin is taking meaningful steps toward housing abundance” (ROP fellow @RyanPuzycki)

Alex Tabarrok says: Don’t Let the FDA Regulate Lab Tests: “Lab developed tests have never been FDA regulated except briefly during the pandemic emergency when such regulation led to catastrophic consequences”

Related, Scott Alexander proposes “a practical abolish-the-FDA-lite policy”: 1. Legalize artificial supplements; 2. An “experimental drug” category, “where they test for safety… but don’t test for efficacy”

“Today, there is a clear bipartisan consensus for far-reaching change at NRC. In the coming weeks, we will find out whether consensus extends to four NRC commissioners tasked with determining the future of advanced nuclear” (via @TedNordhaus)

Jennifer Pahlka on the “kludgeocracy” within government: “red tape and misaligned gears frequently stymie progress on even the most straightforward challenges.” (I also enjoyed this older article from Pahlka: The Problem with Dull Knives)

“The OpenAI governance crisis highlights the fragility of voluntary EA-motivated governance schemes. So the world should not rely on such governance working as intended,” says Jaan Tallinn to Semafor (via @semafor). Semafor describes this as “‘questioning the merits’ of running companies based on effective altruism,” although others have pointed out that it might instead be questioning the reliabliity of self-regulation

“In 1989 Wang Huning envied the daring he found in America. He celebrated a culture willing to engineer its way out of any problem, its drive to slowly build towards utopia.” But now, “on almost every metric Wang discusses for his ‘spirit of innovation’ and ‘spirit of the future’ the Chinese government and society seems to embody these things more than America does” (thread from @Scholars_Stage, summarizing this essay)

“TIL that there are countries where ~10% of the population applies every year for the US visa lottery… Crazy to think that if the US opened its borders, 10% of a country would pack their bags and leave” (@sebasbensu)

“It took a very long time to get here, and we had to change dozens of laws but now you can just go for a 17-story tower of housing in Palo Alto” (@kimmaicutler)

“Remember folks: if no one in your organization was around the last time something was done, you don’t have institutional experience, just institutional records” (@culpable_mink)

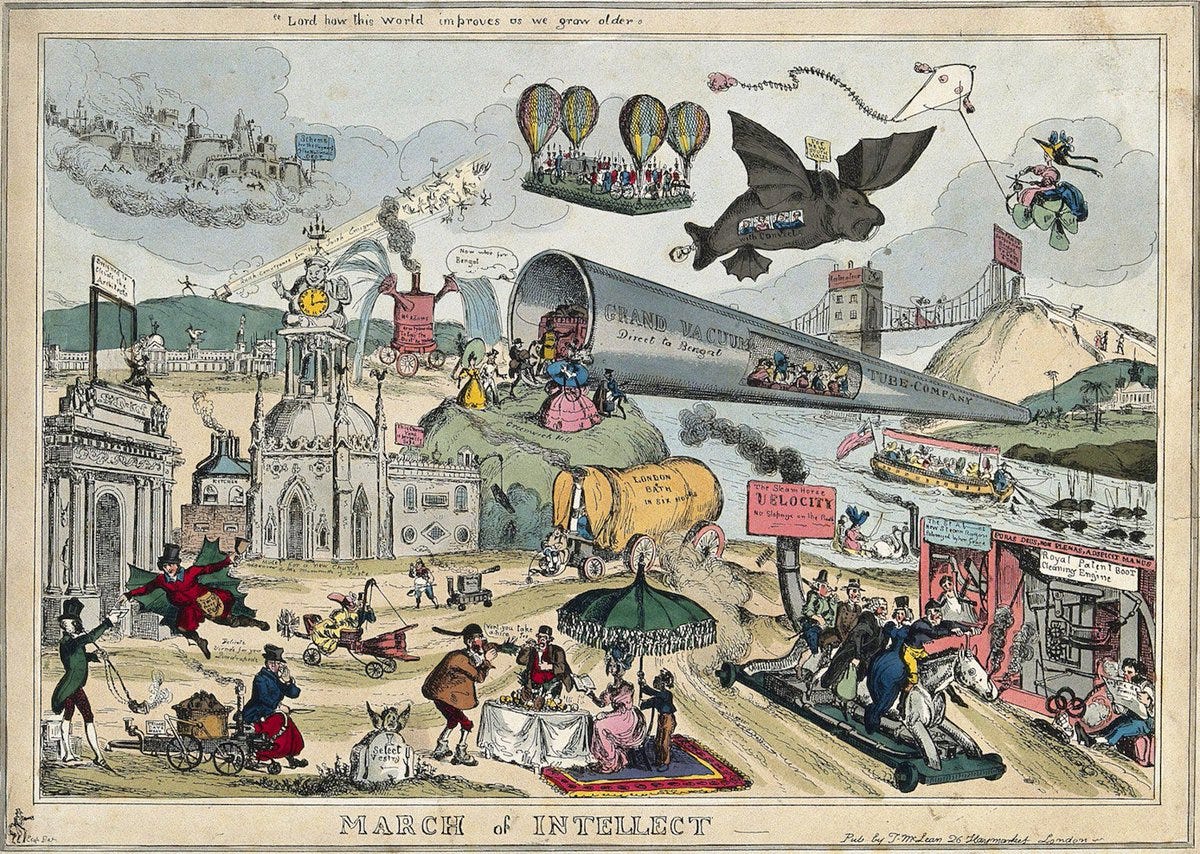

“Every … invention mocked in the same cartoon came to pass within one hundred years, including the railroad, the airship, the airplane, the automobile, the powerboat, and the industrial factory.” (from “Technological Stagnation Is a Choice”, via @balajis and @packyM)

Quotes

Maria Montessori (via @mbateman):

The community of interests, the unity that exists between men, stems first and foremost from scientific progress, from discoveries, inventions, and the proliferation of new machines.

Thomas Edison, quoted by Matt Ridley (via @jonboguth):

I am ashamed at the number of things around my house and shops that are done by animals—human beings, I mean—and ought to be done by a motor without any sense of fatigue or pain. Hereafter a motor must do all the chores.

Samuel Huntington, Who Are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity (h/t @SarahTheHaider)

… from the beginning America’s religion has been the religion of work. In other societies, heredity, class, social status, ethnicity, and family are the principal sources of status and legitimacy. In America, work is. In different ways both aristocratic and socialist societies tend to demean and discourage work. Bourgeois societies promote work. America, the quintessential bourgeois society, glorifies work. When asked “What do you do?” almost no American dares answer “Nothing.”

On nuclear construction cost increases, from Crowley and Griffith 1982, “US construction cost rise threatens nuclear option” (via @whatisnuclear):

The increases are not caused directly by the regulations. Rather, they result from interaction of NRC and industry staffs in an effort to obtain the goals of “zero risk and “zero defects” in an adversarial and legalistic regulatory environment. The pursuit of “zero risk” means that all failure modes have the same importance regardless of their probability of occurrence. The pursuit of “zero defects” encourages continuous expansion of the number of alternatives that must be analyzed and continuous refinements of the requirements. The legal need for “evidence” encourages development of complex analyses rather than simple ones. It also submerges the fact that all engineering analyses are really approximations to actual phenomena because such subjective pos-itions are difficult to defend in court.

The advantage which “precedent” has in the legal environment encourages the adoption of unrealistic and expensive approaches because it is easier than suffering the uncertainty associated with trying to have a new approach accepted. The continuation of this situation for a decade has resulted in the tradition that if a method is more complex, more difficult and more time consuming, it must be safer! The development over the last decade of seismic design criteria and design approaches with respect to piping systems is an example of the situation.

The classic division of authority and responsibilities between engineer, manufacturer and constructor has been distorted by the fear of losing a decision in a regulatory or judicial hearing which would cause political damage to the regulatory agency or financial damage to the utility. Consequently, there has been an ever increasing reliance on academic analytical techniques rather than experienced judgment. The concept of “good engineering practice” is discouraged during construction. Analysts and designers on both regulatory and industrial staffs inexperienced in the realities of hardware and construction practices are making impractical design decisions which have been exceedingly damaging to nuclear industry economics.

Ironically, some of the decisions that have been made in the name of improving safety margins for low probability events, may have reduced the safety margins for high probability events. The UE&C piping study uncovered numerous areas where the tolerances requested in the piping design documents might be appropriate for a machine shop oriented manufacturing operation, but are totally unrealistic for field construction.

Maps and charts

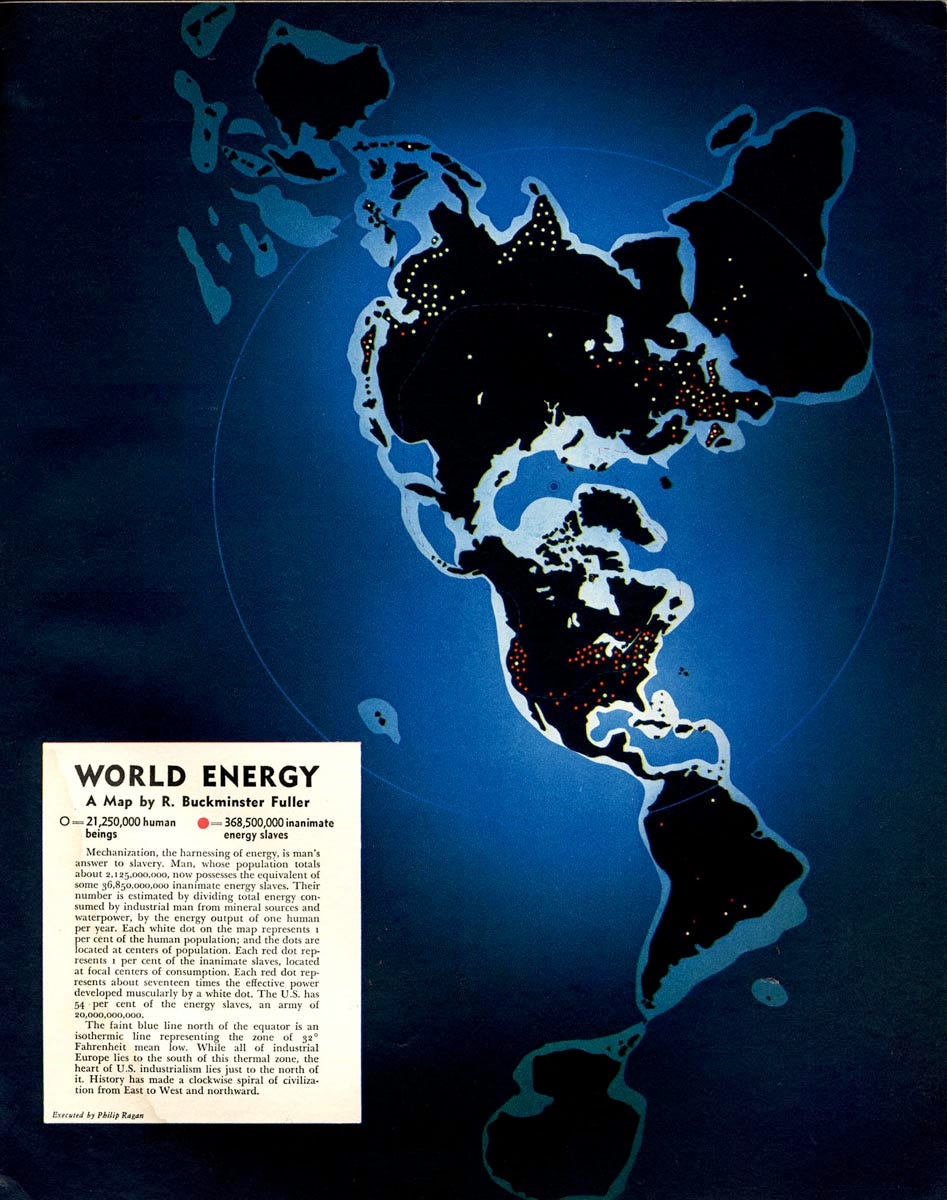

“Mechanization, the harnessing of energy, is man’s answer to slavery” (Buckminster Fuller). Map from 1940, when the world had just over 2 billion people, and machines doing the energy equivalent of 37 billion people’s worth of work for them (Twitter, Threads):

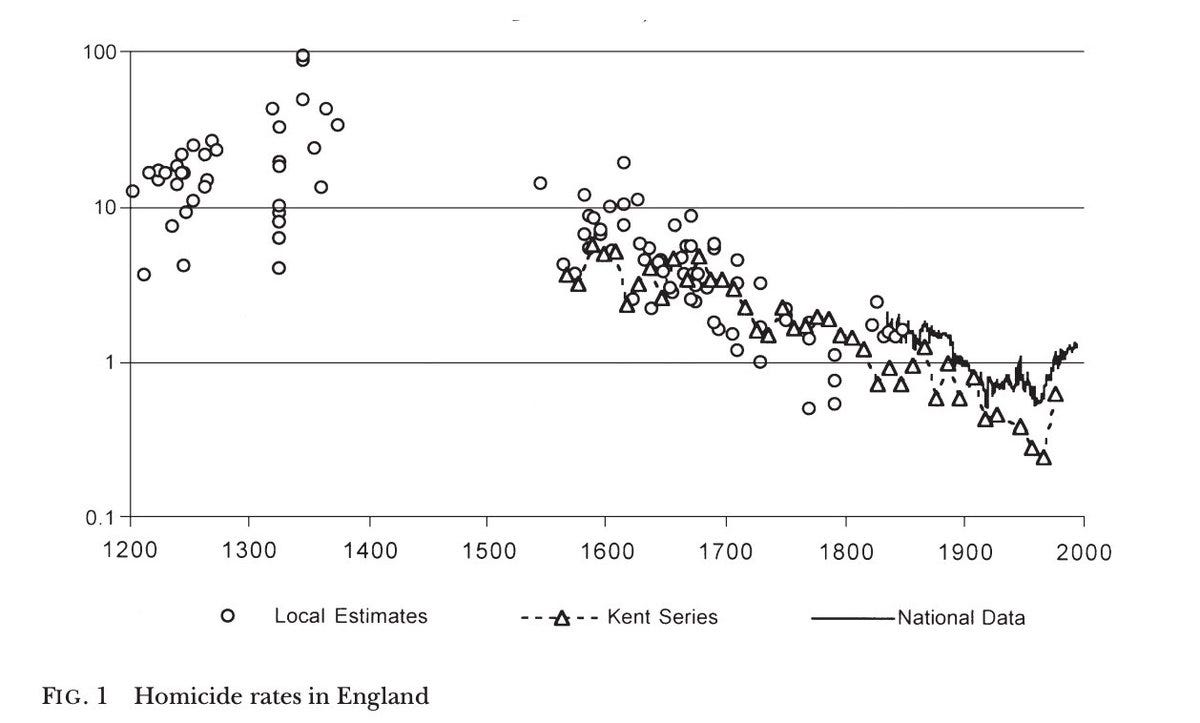

“An incredible 2001 paper re-analysed every then-available dataset on historical European homicide rates. This turned up an amazing trove of estimates. Firstly, England. Note that it’s a log scale – 1300s England was a war zone!” (via @bswud, see the whole thread for more):

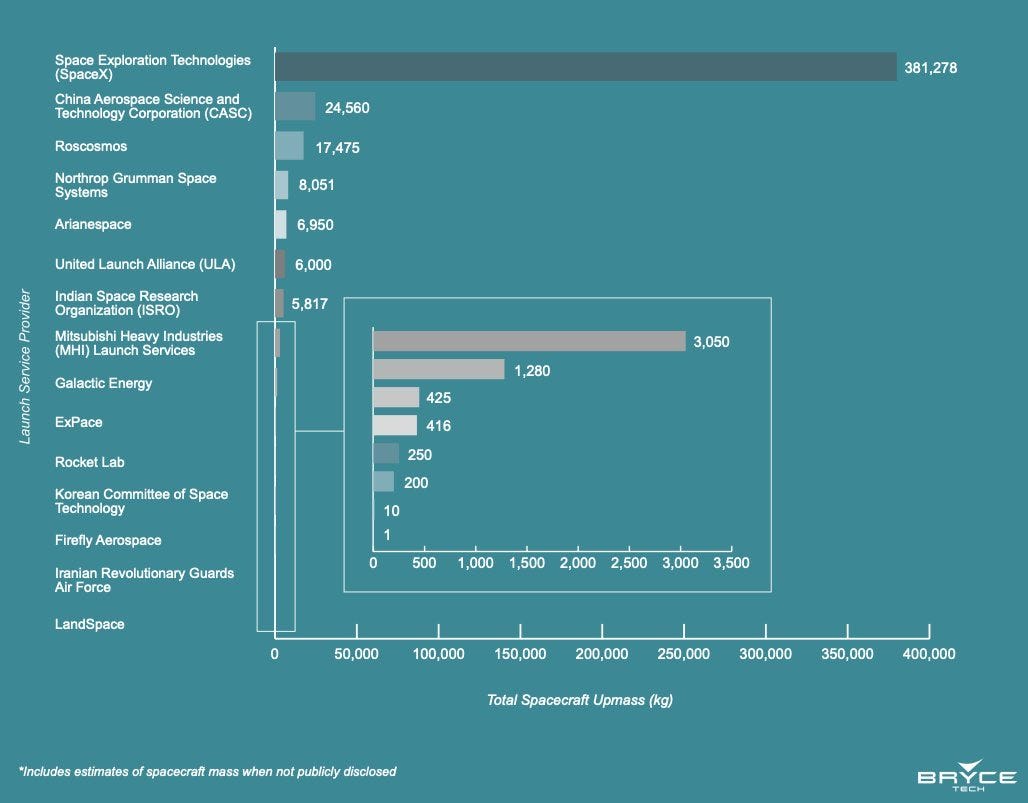

“SpaceX is tracking to launch over 80% of all Earth payload to orbit this year” (@elonmusk)

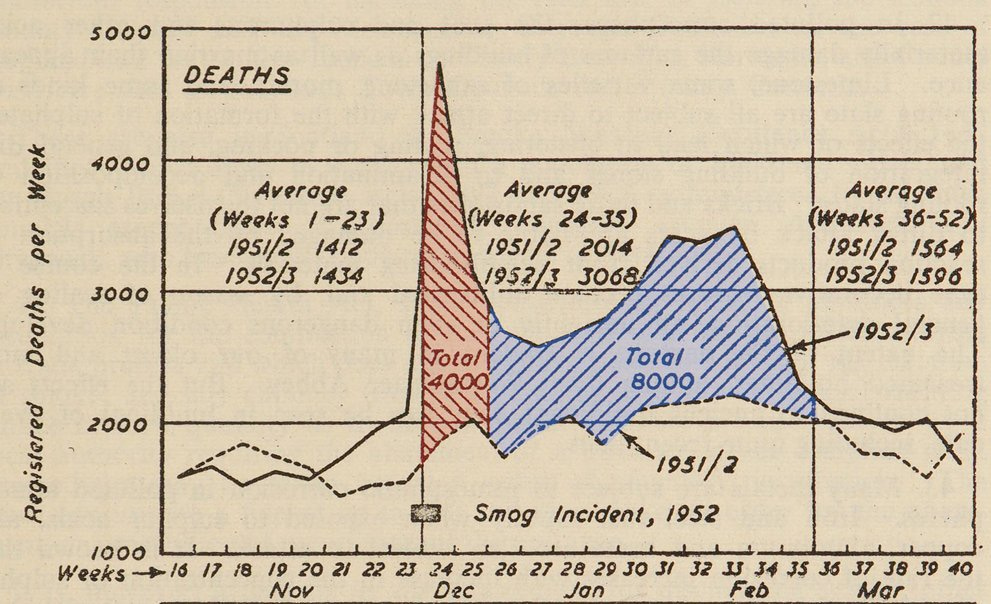

“5th December 1952 marked the start of the horrific Great Smog of London. The smog triggered the process that led to the Clean Air Act in 1956” (@jimmcquaid)

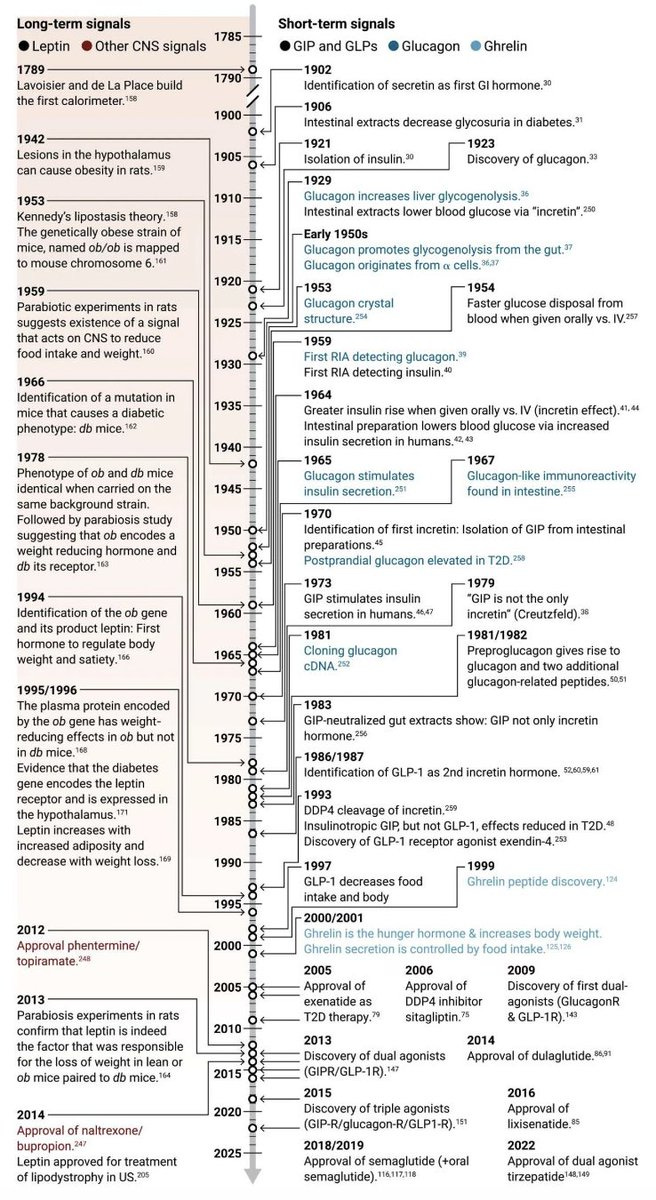

The “journey of the miraculous GLP1 weight-loss drugs: 120 years ago: first basic discoveries in gut hormones; 37 yrs ago: GLP1 identification; 25 yrs ago: discovery that GLP1 decreases appetite” (via @DKThomp)

“Here’s how many new US federal laws were applicable to nuclear power plants from 1954 to 1984” (@whatisnuclear)

“The US increasingly leading in oil production” (@StefanFSchubert)

“Nvidia datacenter revenue, by @Thomas_Woodside” (@paulg):

Original post: rootsofprogress.org/links-digest-2023-12-15

Great musings Jason. Part of the reason why innovation seems to slow down after 1950 could also be changing research incentives, not just the “low hanging fruit” effect. As I wrote:

"Since the 1970s, there has been a growing expectation that researchers not only publish frequently but also publish works that are frequently cited by others (have a large impact). Together, these metrics, known as the “h-score,” are a kind of “batting average” for researchers. The more a researcher publishes and the more his work is cited, the more likely he is to obtain grants and further his career."

In other words, research that stays within well-established and understood areas is rewarded with grants while emerging areas tend not to. The former is likely to be cited more often, while the latter is not.

Great piece on creating evolvable scientific institutions and the currated summary of links after! Thanks.