Announcing our 2023 blog-building fellows

Also: What I've been reading, September 2023

I’m on the new social network Threads as @jasoncrawford, follow me there!

In this update:

Full text below, or click any link above to jump to an individual post on the blog. If this digest gets cut off in your email, click the headline above to read it on the web.

Announcing our 2023 blog-building fellows

This is a guest post by Heike Larson, VP of Programs.

This week, twenty talented progress intellectuals begin their eight-week blog-building intensive journey.

We’re delighted with the quality of these fellows. We selected them out of nearly 500 applicants, after conducting over 80 interviews. It was hard to choose just 20 (and we’re thankful that we were able to raise more funding to welcome 20 instead of 15; it would have been gut-wrenching to say no to 5 more great people: a special callout to our fellowship program supporters, O’Shaughnessy Ventures and alpha.school.)

When we announced this program in July, a crucial open question was “is there enough talent out there worth accelerating?” We now know the answer is a resounding yes. Our fellows:

Will explain and advocate for a wide range of progress topics: from longevity to biotech to health care innovation, from energy abundance to advanced nuclear to water abundance, from eco-modernism to the philosophy of progress, from space to AI to construction to defense tech, from American dynamism to California revitalization, from housing to infrastructure to urbanism, from immigration to meta-science and the philosophy of technology.

→ Imagine the impact we could have if even just 5 out of 20 do for their topics what, for instance, Eli Dourado has done for NEPA and regulatory reform.

Come from a wide range of backgrounds: Think tanks, public policy orgs, and philanthropy (6 people); academics and researchers (3); undergrad and grad students (4); industry (4); and writers and public intellectuals (3). They come from all over the US, and four of them are international (UK, Switzerland, Belgium, and Canada). The youngest is a rising sophomore at Stanford; the oldest is a mid-career professional in their forties.

→ We’re excited that our progress community is built on such a broad base. It’s not a niche movement, but one that resonates in many places and with people from a wide range of backgrounds. Imagine if, through this program and many more cohorts, we have articulate, respected, influential voices for progress in all these fields and places.

Are strong writers and clear, deep thinkers already. We’ll help them get even better and build their audiences. Some already have flourishing blogs with thousands of readers; others write well but to small audiences of dozens or hundreds of people.

→ We will empower them both to write more and better and to grow their audiences, so their ideas have the impact they deserve.

Meet the 2023 inaugural Roots of Progress Blog Building fellows

Over the next eight weeks, we will empower these fellows to become intellectual entrepreneurs for progress. They will:

Be immersed in progress studies—meeting our eleven wonderful program advisors and learning from them

Grow their writing skills in a structured course focused on long-form, persuasive writing for a general audience. They’ll receive feedback and guidance from a professional editor (for many, a first in their careers)

Learn how to grow the audience for their work—a key part of the Write of Passage program

Our goal is to help them 2x their potential—and to build a community that sustains them in their careers as progress intellectuals for years to come. Running the program will answer our second critical question: “Can we actually help these people in their writing and their careers?” We’ll share what we learn on this question over the next several months.

We’re thrilled to have such a great community come together. The tide of history isn’t always carried by the side with the best ideas. It is carried by the side with the intellectuals who are best at presenting and arguing for its ideas. Here’s to twenty intellectuals being empowered to establish the intellectual base of the progress movement!

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/fellowship-announcement-2023

What I've been reading, September 2023

A quasi-monthly feature. Recent blog posts and news stories are generally omitted; you can find them in my links digests. I’ve been busy helping to choose the first cohort of our blogging fellowship, so my reading has been relatively light. All emphasis in bold in the quotes below was added by me.

Books

Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress (1990). I’ve been a big fan of Mokyr ever since the start of this project; his book A Culture of Growth was part of my initial motivation. I’m only a few chapters in to Lever of Riches, but it’s excellent so far. Most intriguing so far is his comment that classical civilization was “not particularly technologically creative” even though it was “relatively literate and mobile, and ideas of all kinds disseminated through the movement of people and books.” In contrast:

Early medieval Europe, sometimes still referred to as a “dark” age, managed to break through a number of technological barriers that had held the Romans back. The achievements of early medieval Europe are all the more amazing because many of the ingredients that are usually thought of as essential to technological progress were absent. Particularly between 500 and 800 A.D., the economic and cultural environment in Europe was primitive compared to the classical period. Literacy had become rare, and the upper classes devoted themselves to the subtle art of hacking each other to pieces with even greater dedication than the Romans had. Commerce and communications, both short- and long-distance, declined to almost nothing. The roads, bridges, aqueducts, ports, villas, and cities of the Roman Empire fell into disrepair. Law enforcement and the security of life and property became precarious, as predators from near and afar descended upon Europe with a level of violence and frequency that Roman citizens had not known. And yet toward the end of the Dark Ages, in the eighth and ninth centuries, European society began to show the first signs of what eventually became a torrent of technological creativity. Not the amusing toys of Alexandria’s engineers or the war engines of Archimedes, but useful tools and ideas that reduced daily toil and increased the material comfort of the masses, even when population began to expand after 900 A.D., began to emerge. When we compare the technological progress achieved in the seven centuries between 300 B.C. and 400 A.D., with that of the seven centuries between 700 and 1400, prejudice against the Middle Ages dissipates rapidly.

Ian Tregillis, The Mechanical (2015), first book in the Alchemy Wars trilogy. A sci-fi novel set in an alternative early 20th century in which humanoid, artificially intelligent robots had been invented in the late 17th century. Gripping and well-told.

A few I’ve just been browsing:

Michael Postan, The Medieval Economy and Society: An Economic History of Britain, 1100-1500 (1972)

W. Brian Arthur, The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves (2009)

Some that have come across my desk but that I haven’t had a chance to crack open:

Akcigit and Van Reenen, The Economics of Creative Destruction: New Research on Themes from Aghion and Howitt (2023)

Todd and King, Miracles and Machines: A Sixteenth-Century Automaton and Its Legend (2023)

Jack Kloppenburg, First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology (1988)

Clifford Pickover, The Loom of God: Tapestries of Mathematics and Mysticism (1997)

AnnaLee Saxenian, Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128 (2006)

Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change (1979)

Agriculture

I’ve been continuing to research agriculture for a chapter in my book.

Bruce Campbell, The Medieval Antecedents of English Agricultural Progress (2007). Key quote:

The ultimate challenge, therefore, was to raise land and labour productivity together in conjunction with a general expansion of agricultural output and growth of population. Only when this had been achieved would the productivity constraints within agriculture cease to impede the progress of the economy at large. It is the resolution of this fundamental dilemma which constituted the so-called agricultural revolution. At its core in England’s case lay, on the one hand, structural and tenurial changes in the units of production—notably the size and layout of farms and terms on which they were held—which transformed the productivity of labour, and, on the other, an ecological transformation of the methods of production, which yielded significant gains in the productivity of land.

The key to the latter, it has long been believed, lay in an enhanced cycling of nutrients facilitated by the incorporation of improved fodder crops into new types of rotation, which allowed higher stocking densities, heavier dunging rates, higher arable yields, more fodder crops, more livestock, and so on in a progressively ascending spiral of progress.

F. M. L. Thompson, “The Second Agricultural Revolution, 1815-1880” (1968). (Mentioned this last time but hadn’t read it yet.) One core idea in this paper is that there were “three different kinds of technical and economic changes” that led from traditional medieval European open-field farming to modern farming. The first involved improved crop rotations that eliminated fallowing. The second was the rise of mineral fertilizers. The third was mechanization. Thompson points out that before the second stage, farms were mostly closed loops:

The essence of the second agricultural revolution was that it broke the closed-circuit system and made the operations of the farmer much more like those of the factory owner. In fact farming moved from being an extractive industry, albeit of a model and unparalleled type which perpetually renewed what it extracted, into being a manufacturing industry.

Other articles

Arnold Kling, “The Two Forms of Social Order” (2015):

In any society, who is allowed to form an organization that competes with powerful economic and political interests? In their 2009 master work, Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History, Douglass North, John Joseph Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast give a striking answer. They say that either almost no one is allowed to form an organization that competes against powerful interests, or almost everyone is allowed to form such an organization. In their terminology, there can be a limited-access order or an open-access order, but nothing in between.

Related: Douglass North, “Economic Performance through Time” (1993), North’s Nobel prize lecture:

The incentives to acquire pure knowledge, the essential underpinning of modern economic growth, are affected by monetary rewards and punishments; they are also fundamentally influenced by a society’s tolerance of creative developments, as a long list of creative individuals from Galileo to Darwin could attest. While there is a substantial literature on the origins and development of science, very little of it deals with the links between institutional structure, belief systems and the incentives and disincentives to acquire pure knowledge. A major factor in the development of Western Europe was the gradual perception of the utility of research in pure science.

Incentives embodied in belief systems as expressed in institutions determine economic performance through time, and however we wish to define economic performance the historical record is clear. Throughout most of history and for most societies in the past and present, economic performance has been anything but satisfactory. Human beings have, by trial and error, learned how to make economies perform better; but not only has this learning taken ten millennia (since the first economic revolution)—it has still escaped the grasp of almost half of the world’s population. Moreover the radical improvement in economic performance, even when narrowly defined as material well-being, is a modern phenomenon of the last few centuries and confined until the last few decades to a small part of the world.

And:

It is the admixture of formal rules, informal norms, and enforcement characteristics that shapes economic performance. While the rules may be changed overnight, the informal norms usually change only gradually. Since it is the norms that provide “legitimacy” to a set of rules, revolutionary change is never as revolutionary as its supporters desire and performance will be different than anticipated. And economies that adopt the formal rules of another economy will have very different performance characteristics than the first economy because of different informal norms and enforcement. The implication is that transferring the formal political and economic rules of successful western market economies to Third World and eastern European economies is not a sufficient condition for good economic performance.

Jamie Kitman, “The Secret History of Lead” (2000). Deeply researched article about leaded gasoline and its health hazards. Tells the story of how it was created, the initial health concerns, how it was approved and deployed anyway, and how the health problems were eventually demonstrated and leaded gasoline phased out (at least in the US). The article is slanted, blaming everything on capitalist greed and accusing government agencies who supported leaded gasoline of being corporate lapdogs, but if you can read past the emotional language, there is a lot of interesting history in here.

It’s still unclear to me where this story should fall on a spectrum from “reckless negligence” to “no one could have known,” but it doesn’t seem to have been all the way on the latter end: lead was generally understood to be toxic since antiquity, and there were “well-known public health and medical authorities at leading universities” who expressed concern over lead additives in gasoline as soon as it was introduced in the early 1920s. There is an important question here of how to regulate substances when there is some reason for concern about health impacts, but nothing approaching proof, especially when the impacts might be subtle and long-term, meaning that data would take a long time to collect. This issue is still unresolved in my mind.

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/reading-2023-09

Links digest: The Conservative Futurist, cargo airships, and more

Announcements

The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised is available for pre-order (via @JimPethokoukis)

Asimov Press is “an editorially-independent venture that will publish books and essays that make sense of biology, AI, and our collective future” (via @AsimovBio and @NikoMcCarty, who will be its first editor)

Statecraft, a new newsletter from the Institute for Progress, is an interview series about how policymakers actually get things done (via @rSanti97)

HumanProgress.org has been revamped, including a new interactive data page that lets you create your own visualizations (via @Marian_L_Tupy)

Maximum New York raised $17,500 of its $150,000 goal in the first week of its fundraiser. Founder Daniel Golliher is also starting chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma—he says the prognosis is good, but send your best wishes (via @danielgolliher)

The US Megaprojects Database, contributions solicited (via @_brianpotter)

New issue of Works in Progress

Issue 12 features:

Making architecture easy. “Buildings should be designed to be agreeable—easy to like—not to be unpopular works of genius”

Growing the growth coalition. “If we want voters to encourage growth near them, we need to make it worth their while”

and more!

Articles

Anton Howes asks: does history have a replication crisis? (via @s8mb)

Video

Veritasium on cargo airships (via @elidourado, who else)

Queries

“I’m looking to talk (on the record) to expert on dealing with the result of car crashes—like an emergency medicine doctor, EMT, etc. Any suggestions?” (@binarybits)

“I want to go to a few talks at Berkeley or Stanford for fun—physics, biology, math + CS but also humanities. Any suggestions for ones w/ high quality content or attendees?” (@LauraDeming)

Quotes

“This then is our task, to gather the highest discoveries that have been made in the sciences, to render them clear and fascinating, and to offer them to childhood.” Montessori (via @mbateman)

“If the world farmer reaches the average yield of today’s U.S. corn grower during the next 70 years, 10 billion people eating as people now on average do will need only half of today’s cropland. The land spared exceeds Amazonia.” Jesse H. Ausubel (via @Marian_L_Tupy)

History

Life before modern communication technology: “Despite being born in the same year and only about 130 kms apart, Bach and Handel never met. In 1719, Bach made the 35-km journey from Köthen to Halle with the intention of meeting Handel; however, Handel had left the town” (@StefanFSchubert)

Related: “The technology in this video is why you and your family don’t have to be subsistence farmers anymore” (@AlecStapp)

“1838: a Congressman is shot and killed in a duel over corruption. 1930s: 1 in 4 Americans are unemployed. 1968: riots break out in 130 cities. 1971-2: 2500+ domestic bombings occur” (@heyemmavarv highlighting points from a WSJ opinion piece via @sapinker, who comments “The best explanation for the good old days is a bad memory: America’s divisions were worse in the past (and not just in the run-up to the Civil War)”)

Misc.

“For most of the time during which anatomically modern humans have existed, there were fewer of them on Earth than there are FLYING IN THE SKY at any given instant today” (@DavidDeutschOxf riffing on @michael_nielsen)

“Despite dire projections of climate impacts, many aspects of human well-being are expected to improve over time. Our climate assessments need to include this context. … How can the outlook be dire but improvements also be expected? It’s because well-being (health, living standards, food security, water security, etc.) is driven by multiple factors, not just climate. Climate effects may be negative while the effects of other drivers (economic development, technology, social change, policy, etc.) may be positive and outweigh climate effects. So, for example, we expect longer lifespans even as warming causes more temperature-attributable deaths, less poverty overall even while climate change pushes some into poverty, fewer people hungry even while climate change exacerbates hunger for some.” (@oneill_bc)

One of the challenges of arguing for (future) progress: (1) People don’t see how the future could be much better, and (2) when you tell them how, they don’t believe you because it sounds like science fiction. Of course, science fiction has come true, over and over again. But many people are only willing to extrapolate current trends, and not the meta-trend that current trends are always broken by new, unforeseen (and unforeseeable) developments. (Threads, Twitter)

“If GPT-4 could explain things to me by showing me simple animations or interactive examples… would learn so much” (@willdepue). This will happen, sooner than most people expect, and it will be amazing

“I’ve read two good books on advertising: David Ogilvy’s Confessions of an Advertising Man, and Byron Sharp’s How Brands Grow. Together they make a cohesive—and contrarian—picture of how advertising works.” Thread by @s_r_constantin

“Furniture doesn’t last long now because you the customer care more about cost than durability” (@robinhanson commenting on WaPo). Related, an old cast iron stove might last 100 years, but the new ones are better

“Using laser scanners with error tolerances below 65 microns,” manufacturers can now “scan, identify defects and effect a simple quick repair” using direct laser deposition, rather than replace highly expensive components: thread by @Jordan_W_Taylor

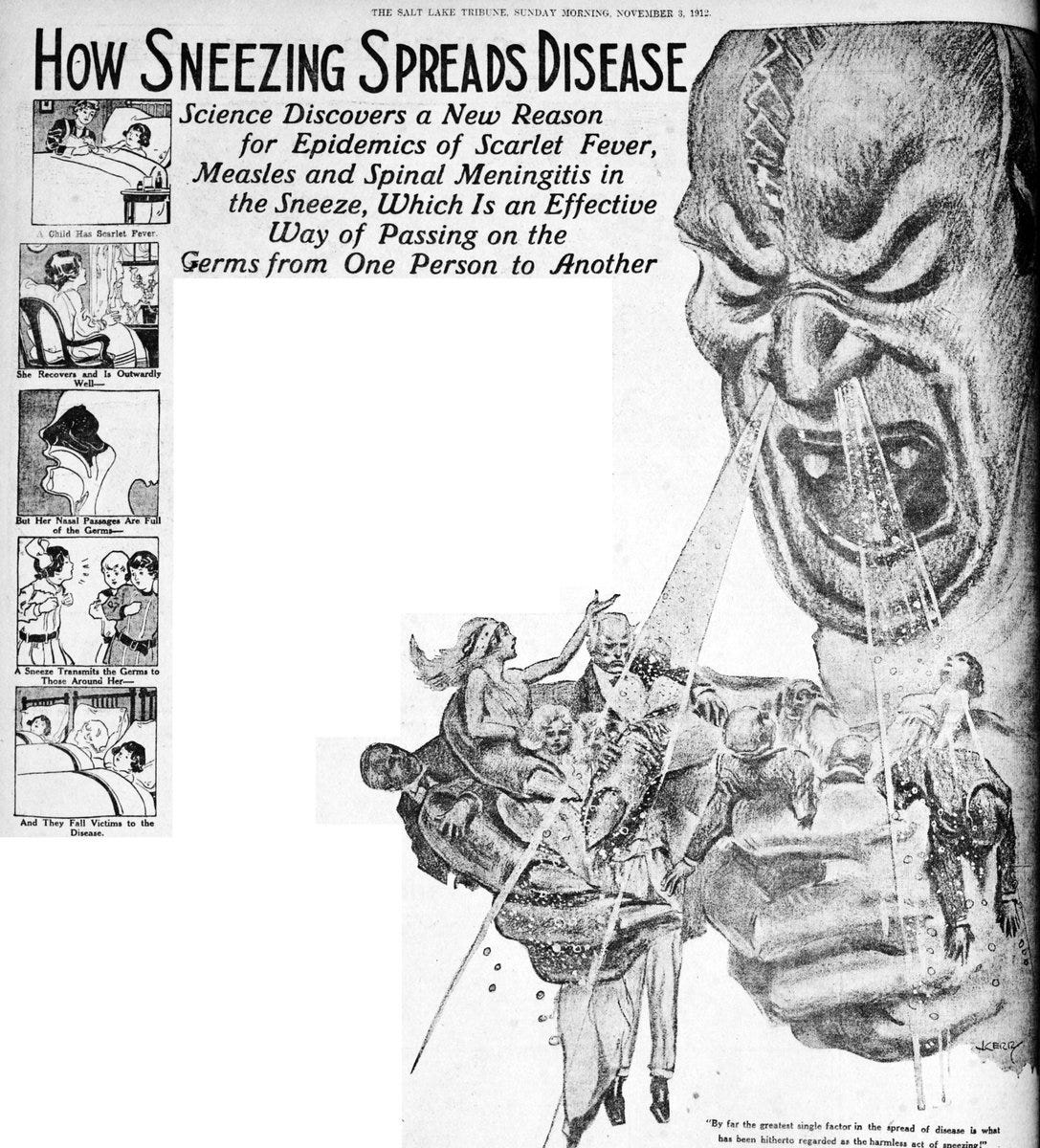

Public health communication in 1912 (@paulisci)

Politics

“I ran preschools for about a decade. The main drivers of child care costs are wages and real estate. Teachers demand higher pay where it’s expensive to live. If we want cheaper child care, we need to make it legal to build lower-cost housing types” (@RyanPuzycki). One more exhibit for The Housing Theory of Everything

Related: “The system isn’t slowing down because it’s failing—it’s slowing down because people are responding rationally to the incentives they face.” Thread from @MichaelDnes1 on what might speed up UK infrastructure. See also his previous thread on why it is slow in the first place, especially this diagram: “It takes 5.5 years to get to the point at which you can put a spade in the ground, assuming everything goes to plan”

“If you saved $100,000 USD of pesos in 1995, they’d be worth $137 USD today. Argentina has seen an average of 100% annual inflation for the last century” (@devonzuegel)

“It’s weird that people consider UBI some newfangled, speculative idea. In every way that matters ‘UBI’ is identical to ‘welfare’ ‘the dole’ etc. This has all been debated without pause since about twelve seconds into the Industrial Revolution” (@benlandautaylor)

“We need a concerted campaign against public clutter. Cookies banners, consent boxes, excessive street signs & markings, pointless loud safety announcements, etc—each one is small by itself, but they all add up and make everyday life uglier and more of a complicated hassle” (@s8mb). Leftover covid signage is a good example

“Single stair, no setbacks, buildings touching. All illegal in the United States or Canada, but legal everywhere else. They also win international awards. Maybe our [building] codes suck?” (@pushtheneedle commenting on @Architizer’s post about a building using prefab wood, 5 levels built in 10 days)

Startups

“‘Give yourself a lot of shots to get lucky’ is even better advice than it appears on the surface. Luck isn’t an independent variable but increases super-linearly with more surface area—you meet more people, make more connections between new ideas, learn patterns, etc” (@sama). Related, Marc Andreessen on the four kinds of luck

“Think of your favorite startup. No matter how good they look, I guarantee you they have almost died, multiple times, for reasons dumber then you can imagine. Their internal org is probably mostly chaos. Don’t be too hard on yourself. Just keep building as fast as possible” (@thegarrettscott)

“It’s funny how heretical this statement is but: some of us really really like working hard on things that are important to us, especially surrounded by caring and sometimes brilliant people. No mojitos on the beach can possibly compete with that” (@tobi)

Charts

Solar deployment is now happening at a roughly $500B annualized rate (via @patrickc, who asks, “Which technology deployments were larger than this? The US’s aircraft production during WWII seems to have peaked at maybe $400B (inflation-adjusted). Global datacenter construction appears to be maybe $200B/year.”)

Pics

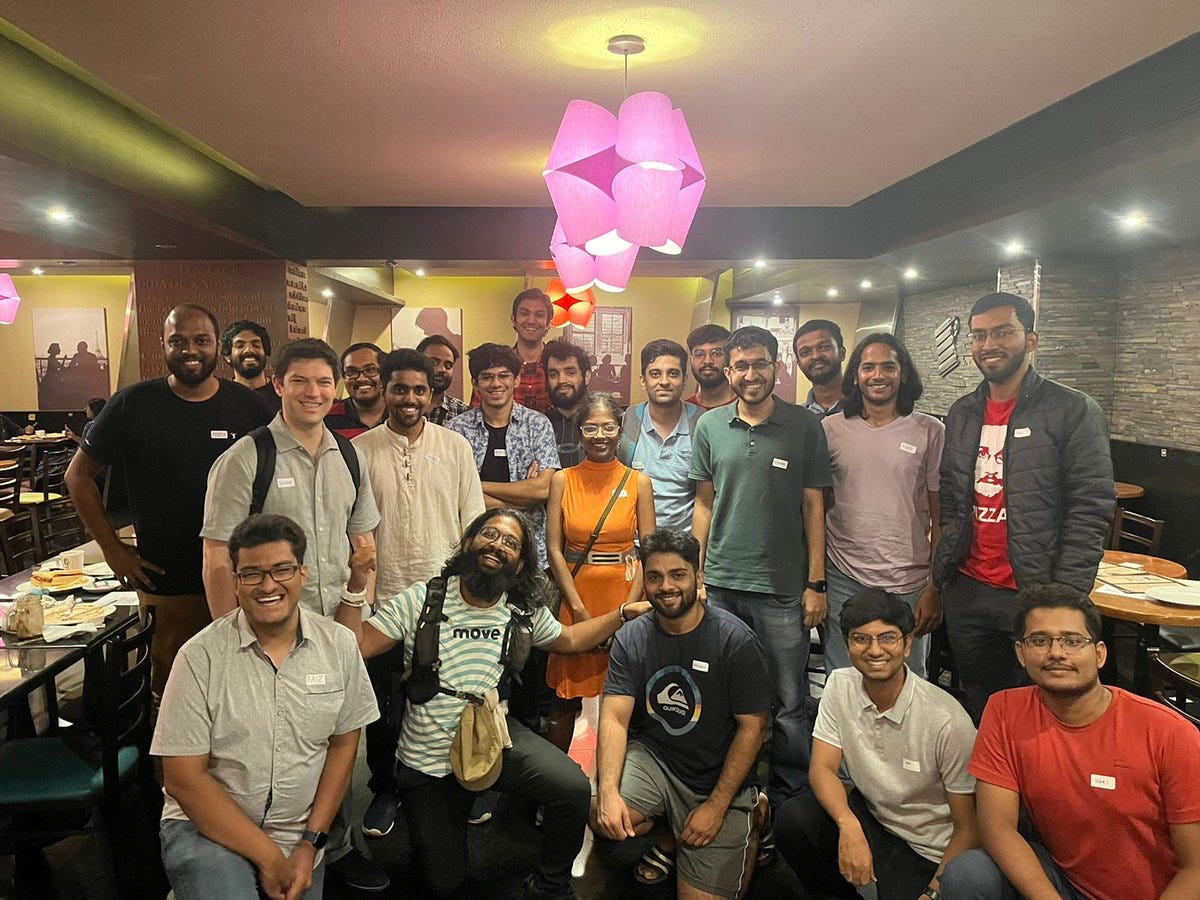

Had a great time meeting locals and chatting about progress at the Bangalore LessWrong / Astral Codex Ten meetup

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/links-digest-2023-09-08

Congrats to all the new fellows! Looking forward to read your progress writing