Think wider about the root causes of progress

Also: 2022 in review, Build for Tomorrow podcast with Jason Feifer

This is a long one, which will probably get clipped in your browser. Click the title to read the whole thing online.

In this update:

This email digest is now on Substack. If you have a Substack yourself, and you enjoy my writing, I’d love a recommendation—thank you!

Think wider about the root causes of progress

Too much discussion of the Industrial Revolution is myopic, focused narrowly on a few highlights such as steam and coal. The IR was part of broader trends that are wider in scope and longer in time than its traditional definition encompasses. To understand anything, it is crucial to get the correct scope for the phenomenon in question.

Here are some ways in which we have to widen our focus in order to see the big picture.

Wider than coal and steam

Some explanations of the IR focus on steam engines, and especially on the coal that fueled them. Economist Robert Allen, for instance, has one of the best-researched and most convincing arguments for cheap coal as a requirement for the development of steam power.

A weak version of this claim, such as “coal was a crucial factor in the IR,” is certainly true. But sometimes a much stronger claim is made, to the effect that the IR couldn’t have happened without abundant, accessible coal, and that this is the main factor explaining why it happened in Europe and especially in Britain. Or more broadly, that all of material progress is driven by fossil fuels (with the implication that once we are, sooner or later, forced to transition away from fossil fuels—whether by geology, economics, or politics—growth will inevitably slow).

But much of the early IR wasn’t dependent on steam power:

Textile machinery, such as Arkwright’s spinning machines, were originally powered by water.

Henry Maudslay’s earliest machine tools were made to manufacture locks; another key application of machine tools was guns with interchangeable parts. This was not motivated by steam power.

Improvements in factory organization, such as the arrangement of Wedgwood’s pottery manufacturing operation, were management techniques, independent of power sources.

The reaper was pulled by horses—even after the development of steam power, because steam tractors were too heavy for use in fields. Even stationary agricultural machines such as for threshing or winnowing were often muscle-powered.

You could argue that all of these inventions would have reached a plateau and would not have had as much economic impact without eventually being hooked up to steam or gas engines. But the fact remains that they were initially powered by water or muscle, and they were economically useful in those first incarnations, often achieving 10x or more gains in productivity. They didn’t need coal or gas for that, nor were they invented in anticipation that such power would soon be available.

So either it was an amazing coincidence that all of this mechanical invention was going on at the same time—or there was some wider, underlying trend.

Wider than industry

Further, the IR itself only represents a subset of the broader technical innovations that were going on in this period. Here are a few key things that aren’t considered “industrial” and so are often left out of the story of the IR:

Improvements to agriculture other than mechanization: for instance, new crop rotations

Improvements to maritime navigation, such as the marine chronometer that helped solve the longitude problem

Immunization techniques against smallpox: inoculation and later vaccination

To me, the fact of all these inventions happening in roughly the same time period indicates a general acceleration of progress during this time, reflecting some deep cause, not a simple playing out of the consequences of one specific resource or invention.

Wider than invention

In many areas, incremental improvements were being made even before the major inventions that make the history books:

Roads and canals were improved in the 17th and 18th centuries, speeding up transportation even before railroads

Experiments by engineers like John Smeaton created more efficient water wheels, making more usable energy available even before steam power

Sanitation was improved in cities—including cleaner water, better sewage, and some insect control—decreasing mortality rates even before vaccines or the germ theory

A theory of progress should explain these improvements as well as breakthrough inventions.

Wider than scientific theory

Many of the developments discussed above were made by “tinkering,” before the scientific theory that would ultimately explain them. This has led some to suggest that science wasn’t important for the IR.

I think this is based on too narrow a concept of science. Science is not just theories or laws; it is also a method, and the method includes careful observation, deliberate experimentation, quantitative measurement, the systematic collection of facts, and the organizing of those facts into patterns. Those methods were at work in, for instance, Smeaton’s water wheel experiments, or in inoculation and vaccination against smallpox.

More broadly, the creation of scientific theory is too narrow a concept of the goal of the Baconian program. The program was to collect, systematize, and disseminate useful knowledge—at all levels of abstraction, from the broadest theories all the way down to practical techniques. Naturally, the projects that aimed directly at useful techniques first achieved the earliest results, and those that aimed at theoretical understanding achieved later but more powerful results.

Wider than one century

If we widen our view in time as well, we immediately perceive crucial inventions and discoveries well before the IR. The two that stand out most to me are the improvements in navigation that led to the Age of Discovery, and the printing press—both around the 15th century.

The printing press lowered the cost and increased the volume of communication, including scientific and technical writing. The voyages of discovery led to global trade, which drove the growth of port cities such as London, made new products available to consumers, and generally created economic growth.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that these developments preceded the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions by just a couple of centuries—I see a straight line from the former to the latter.

Wider than material progress

Finally, we miss the big picture if we only think about material progress—scientific, technological, industrial, economic—and ignore progress in morality, society, and government.

Consider that, coincident with the Industrial Age, we have also seen the replacement of monarchy with republics, the virtual end of slavery, equal rights for women, and an international consensus against using war to acquire territory. (There are caveats one could add to each of those achievements, but the overall trend is undeniable in each case.) See my review of Pinker’s Better Angels for many relevant details.

Again, something deeper has been going on—deeper even than science, technology and industry.

Not a coincidence

It’s not a coincidence that several non-steam powered mechanical inventions were created around the same time as the steam engine. Or that several non-mechanical innovations were created around the same time as the mechanical ones. Or that the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions happened within a century or two of each other, and in the same region of the world—after millenia of relatively slow progress in both knowledge and the economy. Or that new ways of thinking about government and society came about at the same time as new ways of thinking about science and technology.

There must be some very deep underlying trend that explains these non-coincidences. And that is why I am sympathetic to explanations that invoke fundamental changes in thinking, such as Pinker’s appeal to “reason, science, and humanism” in Enlightenment Now.

You can argue with that explanation—but any theory that ends at “coal” can explain at most a small piece of the puzzle. Such explanations miss the big picture.

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/think-wider

2022 in review

2022 was another big year for me and for The Roots of Progress. This is my annual review—the one post a year (other than timely announcements) where I go meta and give an update on this project. If you want stuff like this more frequently, you can support me on Patreon or make a donation to get my monthly supporter update.

This year had several highlights. We announced a major expansion of this nonprofit effort and hired a CEO to lead it. I concluded my lecture series, “The Story of Civilization,” and am now writing a book based on the same content. I was interviewed for major publications, spoke at some of the top progress conferences, and co-hosted a couple of events myself. Most importantly, I had a couple of banger tweets.

But I’m going to bury all of those ledes in order to start, as is my tradition, with what I suspect is more interesting to my audience: a selection of this year’s…

Reading

The book that fascinated me most this year was American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm, 1870–1970, by Thomas P. Hughes, a finalist for the 1990 Pulitzer. The book is not only about the century of technological enthusiasm, but also about how that enthusiasm (in my opinion) went wrong, and how it came to an end. My review of this book was so long that I broke it into two parts: one on American invention from the “heroic age” to the system-building era and one on the transition from technocracy to the counterculture. (I may at some point do a third part, on the aesthetic reaction to modernism.) Among the more mindblowing facts I learned from this book are that Stalin made “American efficiency” a part of Soviet doctrine, and that Ford’s autobiography “was read with a zeal usually reserved for the study of Lenin.” Overall this greatly strengthened my understanding of technocracy, one of my themes for this year (see below).

A close runner-up for favorite book I read this year was The Control of Nature, by John McPhee. The book tells three stories: about the dams and levees that control the flow of the Mississippi River, the 1973 Eldfell volcanic eruption in Iceland, and the periodic landslides in the San Gabriel Mountains near Los Angeles. It’s fascinating to reflect on how nature is truly indifferent to human needs. Even something we take for granted, such as the course of a river, has to be actively, artificially maintained if it matters to humans.

I also finished reading The New Organon and New Atlantis, both by Francis Bacon. In addition to the parts everyone knows (“knowledge is power,” “nature to be commanded must be obeyed,” etc.), most of Organon is devoted to explaining a long list of specific ways that scientists should observe nature and types of evidence they should collect. In some ways he is amazingly prescient (he figures out, essentially correctly, that heat is a form of motion); in others he is surprisingly behind (he rejected the heliocentric theory as late as the 1620s). Most relevant to my work is his argument for why we should expect progress to be possible: he cites previous inventions and discoveries, including the compass, gunpowder, and the printing press, and extrapolates from these to imagine that there are more inventions waiting to be discovered—which there were. Continuing the theme of historical works, I also read some of Philosophical Letters: Or, Letters Regarding the English Nation, by Voltaire, including the letter on smallpox inoculation.

A major research theme of mine this year was economic growth theory. Highlights from my research here include:

“Paul Romer: Ideas, Nonrivalry, and Endogenous Growth,” by Chad Jones (2019). Explains Romer’s Nobel-winning work and places it in historical context.

Paul Romer’s blog. “It is the presence of nonrival goods that creates scale effects…. if A represents the stock of ideas it is also the per capita stock of ideas.“ (From this post, emphasis added.)

“Endogenous Technological Change,” by Paul Romer (1990). The paper that established the importance of the “nonrivalry” of technology, and won Romer the Nobel in 2018.

“The Past and Future of Economic Growth: A Semi-Endogenous Perspective,” by Chad Jones (2022). Key quote: “Despite the fact that semi-endogenous growth theory implies that the entirety of long-run growth is ultimately due to population growth, this is far from true historically, say for the past 75 years. Instead, population growth contributes only around 20 percent of U.S. economic growth since 1950. … This framework strongly implies that, unless something dramatic changes, future growth rates will be substantially lower. In particular, all the sources other than population growth are inherently transitory, and once these sources have run their course, all that will remain is the 0.3 percentage point contribution from population growth. … the implication is that long-run growth in living standards will be 0.3% per year rather than 2% per year—an enormous slowdown!”

Two classics: “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth” (1956) and “Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function” (1957), both by Robert Solow, for which he won the Nobel prize in 1987. In the first, he defines a model of the economy that includes technical change as well as capital and labor; he shows that capital accumulation alone can’t support long-term economic growth, but technological progress can. In the second, he shows how to measure the effects of technical change, and finds they are much larger than the effects of capital.

The much-discussed “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?,” by Bloom, Jones, Van Reenen, and Webb (2020). Sustaining exponential growth requires exponentially increasing inputs as well, as we continually pick off more of the low-hanging fruit.

“The New Kaldor Facts: Ideas, Institutions, Population, and Human Capital,” by Jones & Romer (2010). A review of what growth theory has accomplished so far, in terms of the facts it can explain, and what the agenda should be going forward.

A few interesting papers on very long-run growth: “Population Growth and Technological Change: One Million B.C. To 1990” by Kremer (1993) and “Long-Term Growth As A Sequence of Exponential Modes” by Robin Hanson (2000).

“On the Mechanics of Economic Development,” Robert Lucas (1988). This bit from the introduction has been widely quoted: “I do not see how one can look at figures like these [the widely varying income levels and growth rates around the world] without seeing them as representing possibilities. Is there some action a government of India could take that would lead the Indian economy to grow like Indonesia’s or Egypt’s? If so, what, exactly? If not, what is it about the ‘nature of India’ that makes it so? The consequences for human welfare involved in questions like these are simply staggering: Once one starts to think about them, it is hard to think about anything else.”

Continuing with some noteworthy books:

The Making of the Atomic Bomb, by Richard Rhodes. The definitive, Pulitzer prize–winning account. I learned new things about the development of nuclear physics and of the industrial and managerial challenge of building and testing the bomb. For instance, creating the first critical pile of uranium was a serious technical challenge even after the basic physical theory had been worked out (you have to get very pure materials, build it in just the right shape, etc.) The book also presents both the abject horror of the bomb’s effects on Hiroshima, and also the reasons why the US felt they had to use it—a fair treatment in my opinion.

Nanofuture, by J. Storrs Hall (author of Where Is My Flying Car?) Gave me a clearer idea about how nanotech could possibly work, and what amazing things it might make possible. One misconception I had was that nanomachines would be small molecules. In fact, even a single component like a gear or bearing will consist of dozens if not hundreds of atoms (e.g., see this diagrammatic illustration of nanogears).

How the World Became Rich, by Koyama & Rubin. A book-length academic literature review of economics & econ history work on the key questions of what caused the Great Enrichment, why some countries have caught up to the West, and why others have not. See reviews by Joel Mokyr and Davis Kedrosky.

The Ghost Map, by Steven Johnson. A history of the Broad Street cholera outbreak and John Snow’s pioneering epidemiology work. I knew that the early sanitation reformers, such as Edwin Chadwick, didn’t necessarily believe in the germ theory and guided their sanitation efforts by sensible qualities such as sight, taste, and smell—I hadn’t realized that Chadwick was a committed miasmatist, so much so that in his crusade to get human waste out of the trenches and cesspools of London, he dumped it into the Thames, fouling that river and actually exacerbating cholera epidemics, the opposite of his stated goal.

Dreams of Iron and Steel, by Deborah Cadbury. I read the chapter on Joseph Bazalgette and the London sewer system, from which I learned that steam engines were key to the system, pumping sewage from lower levels to higher ones so it can flow downhill.

Flintknapping, by John Whittaker. A guide to how stone tools are made, written for both the archaeologist and the hobbyist. Probably much more than you want to know about stone tools, but it helped me understand one of the first technologies.

The Substance of Civilization: Materials and Human History from the Stone Age to the Age of Silicon, by Stephen Sass. Exactly what it says on the tin.

Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk, by Peter Bernstein. An interesting book that doesn’t quite live up to its title; it’s at most a history of financial risk.

How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, by Bill Gates. A good summary of the techno-optimist/ecomodernist approach to climate change.

The Economy of Abundance, by Stuart Chase, who coined the term “New Deal”. I’ve only glanced through this one but it was enough to have an interesting conversation with Jason Feifer on his podcast. Pair with the classic “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren”, by John Maynard Keynes (1930).

The Communist Manifesto, by Karl Marx. Unlike Das Kapital, you can read this is one sitting. I learned less than I was hoping for about Marx’s critique of capitalism; I learned more than I expected about his critique of all other socialists.

Interesting articles and papers:

“The Great American Fraud,” by Samuel Hopkins Adams. A series of articles that ran in Collier’s 1905–06 on the fraudulent practices of the patent medicine industry. Many of the medicines did not work, some were actively harmful, and many made fraudulent claims of being able to cure tuberculosis, cancer, and many other diseases.

“Notes on The Anthropology of Childhood,” by Julia Wise. Children today get far more love, attention, and developmental help than those in primitive societies.

“Coffeehouse Civility, 1660-1714: An Aspect of Post-Courtly Culture in England,” by Lawrence Klein (1996). In the 1600s, coffeehouses were the equivalent of social media—a place to chat, gossip, and hear the news—and they received many of the same criticisms. Coffeehouses were denounced because they ”allowed promiscuous association among people from different rungs of the social ladder,” ”served as an unsupervised distribution point for news,” and ”encouraged free-floating and open-ended discussion” (which today we call “unfettered conversations”). One writer called them “the midwife of all false intelligence” (which today we call “misinformation” or “fake news”). King Charles II almost banned coffeehouses in 1675.

“The Mechanics of the Industrial Revolution,” by Kelly, Ó Gráda, and Mokyr (2022). The title is a pun: it’s about both the details of how the Industrial Revolution happened, and the craftsmen with machine-building skill who were crucial to it. Davis Kedrosky has a good summary.

“Time is money: a re-assessment of the passenger social savings from Victorian British railways,” by Timothy Leunig. Estimates that “railways accounted for around a sixth of economy-wide productivity growth” in the period 1843–1912.

“Development work versus charity work,” by Lant Pritchett. “I am all for the funding of cost-effective targeted anti-poverty programs. But while it is optimal to do both, we development economists should keep in mind that sustained economic growth is empirically necessary and empirically sufficient for reducing poverty (at any poverty line) whereas targeted anti-poverty programs, while desirable, are neither necessary nor sufficient. Advocates of poverty programs say things like ‘growth is not enough’ or that poverty programs are ‘equally important’ as economic growth but these claims are just obviously false.” (Thanks to Patrick Collison for bringing Pritchett’s work to my attention.)

“A Shameless Worship of Heroes,” by Will Durant. ”For why should we stand reverent before waterfalls and mountain tops, or a summer moon on a quiet sea, and not before the highest miracle of all—a man who is both great and good?” (Hat-tip: Nico Perrino.)

Finally, I don’t read much fiction these days, but over winter vacation I indulged in a few novels. The Lighthouse at the End of the World, by Jules Verne, is not a science-fiction story but rather something of a naval adventure, taking place on an island at the southern end of Tierra del Fuego. Lest Darkness Fall, by L. Sprague de Camp, is a sci-fi classic about an archaeologist who is zapped back in time to just after the fall of the Roman Empire, and who makes it his quest to prevent the Dark Ages.

Books I’m in the middle of and will probably feature in next year’s list include Robert Allen’s The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, and Virginia Postrel’s The Future and Its Enemies.

My bibliography, I’m afraid, is hopelessly out of date; I’d love to update it with the last couple years of reading in 2023.

Writing

I wrote 28 essays (including this one) in 2022, mostly published here on the blog—over 50k words in total, a bit more than last year.

My top essays by views were:

Some themes this year included:

The progress movement. Key essays here include a feature I wrote for Big Think magazine, “We need a new philosophy of progress,” and pieces on the key concepts of progress, humanism, and agency, on the meaning of the term “philosophy of progress”, and on what a thriving progress movement would look like.

The drivers of growth and progress. My framework here is one of overlapping flywheels, which I applied to explain why progress was so slow for so long. I also wrote about a framework for thinking about inventions that seem to have arrived late, and about how we have to consider a very wide range of developments in order to understand progress in any area. Diving into the academic literature on economic growth theory (see reading above), I also drafted a long essay on “ideas getting harder to find”, which I posted for comment but haven’t revised yet.

Technocracy, the idea that progress should be pursued via top-down control by a technical elite (which, to be clear, I do not endorse). I wrote first about a few threads in my reading that made me aware of this concept, followed up with one more thread from the Space Race, and went into much more depth in my review of American Genesis.

In 2022, rootsofprogress.org got almost 135k unique visits and over 250k pageviews. My email newsletter, which is now on Substack, grew almost 30% to about 7,400 subscribers. (If you have a Substack yourself, and you enjoy my writing, I’d love a recommendation—thank you! Here are the Substacks I recommend.)

Book

My big writing project is a book. It’s about the major discoveries and inventions that created industrial civilization and gave us our standard of living, and why technological/industrial progress can and must continue.

Last year, I began a series of talks based on the outline of the book, going through it chapter by chapter. This year, I wrapped that up. Through that process, I completed the first pass of research for the book, and developed a more detailed outline and plan for each chapter.

Right now I’m talking to literary agents and working on a book proposal. I hope to have a book deal with a publisher by Q1 of 2023.

My goal is to make this book a cornerstone of the progress movement, laying the foundation for the new philosophy of progress.

Organization

Another major project this year was laying the foundation to take The Roots of Progress, as an organization, to the next level.

Last year, I announced that this blog was becoming a one-man nonprofit research organization. Early in 2022, seeing how much much energy and support there is for my mission, it became clear to me that this organization shouldn’t remain focused solely on my own research and writing. So I spent a lot of time and energy this year planning a major expansion of our activities: the launch of a new progress institute.

One thing we needed was a strategy: a way to focus and prioritize our efforts on a set of programs that would have a real, measurable impact. Prodded by some thoughtful advice from Tyler Cowen, we decided that our initial focus should be on creating the public intellectuals who will build this foundation. Our flagship program will be a “career accelerator” fellowship for progress writers with ambitious career goals. The fellowship will help them hit those goals by providing money, coaching, marketing and PR support, and connection to a broader network. Our vision is that in ten years, there are hundreds of progress intellectuals who are alums of our program and part of our network, and that they have published shelves full of new books in progress studies.

The other thing we needed was a CEO to lead this effort. I was very happy recently to announce that we have found a CEO: Heike Larson. Heike has been following my work for a long time, and shares my passion for human progress. She also has excellent qualifications, including 15 years of VP-level experience in sales, marketing, and strategy roles in a variety of industries, from education to aircraft manufacturing. She will take on all management and program responsibilities; I will remain President and intellectual leader of the organization. I’m excited for her to start in January!

We’re at an exciting moment in history. Momentum is growing for progress studies and the “abundance agenda,” and there is a chance for this to shape the 21st century. But the movement needs a driving force, and careful steering. That is where we hope to contribute.

Progress Forum

Another big thing this year was the launch of the Progress Forum, the online home for the progress community.

The primary goal of the Forum is to provide a place for long-form discussion of progress studies and the philosophy of progress. It’s also a place to find local clubs and meetups. The broader goal is to share ideas, strengthen them through discussion and comment, and over the long term, to build up a body of thought that constitutes a new philosophy of progress.

I’m very pleased with the quality of content we’ve gotten so far. Original submissions include:

Why progress needs futurism, by Eli Dourado

Nature of progress in Deep Learning, by Andrej Karpathy (Director of AI, Tesla)

Guarantee Funds / Leveraged Philanthropy, by Anton Howes

Some writers post drafts on the Forum for comment before publishing them to a wider audience, such as:

The Democracy of the Future, by Tomas Pueyo

Pre-publication draft of “Death is the Default: Why building is our safest way forward”, by Gena Gorlin

Plus some cross-posts of great essays from Twitter threads and from other blogs and publications:

Defending Dynamism and Getting Stuff Done, by Virginia Postrel (author, columnist, former editor of Reason magazine)

Is Innovation in Human Nature?, by Anton Howes

New Industries Come From Crazy People, by Ben Landau-Taylor

Where are the robotic bricklayers?, by Brian Potter (cross-posted from Construction Physics)

When should an idea that smells like research be a startup?, by Ben Reinhardt (PARPA)

Science is getting harder, by Matt Clancy (Senior Fellow, Institute for Progress)

It’s time to build: A New World’s Fair, by Cameron Wiese

The Terrapunk Manifesto - a Solarpunk alternative (highly recommended), by Jack Nasjaq

Bombs, Brains, and Science, by Eric Gilliam

One Process (on the nature of innovation, highly recommended), by Jerry Neumann

Wait, Environmentalists Are Anti-Technology?, by Alex Trembath (The Breakthrough Institute)

Interland: The Country In The Intersection, by Maxwell Tabarrok

Effective Altruism and Progress Studies, by Mark Lutter

Huge thanks to the people who worked to create the Forum: Lawrence Kestleoot, Andrew Roberts, Sameer Ismail, David Smehlik, and Alec Wilson. Thanks also to Kris Gulati for nudging this project along, and to Ruth Grace Wong for helpful conversations about community and moderation. Special thanks to the LessWrong team for creating this software platform, and especially to Oliver Habryka, Ruby Bloom, Raymond Arnold, JP Addison, James Babcock, and Ben Pace for answering questions and helping us customize this instance of it. And finally, thanks to Ross Graham, who has been helping recruit great users and content.

Interviews and speaking

Probably my most prominent interview this year was with the BBC, who ran an article on progress studies and quoted me as a spokesman for the movement, along with Tyler Cowen, Holden Karnofsky, and others. It was well-researched and, although somewhat critical, pretty fair in how it represented the progress community.

I did about twenty interviews and fireside chats in all this year, including with the Tony Blair Institute, the Foresight Institute (twice), Jim Pethokoukis (twice), Jason Feifer’s Build for Tomorrow, and the French-language Canadian magazine L’actualité (“Le bien-être de l’humanité passe par le progrès”). I think the most fun and interesting interview, however, was on the podcast Hear this Idea, with Fin Moorhouse and Luca Righetti.

Turning the tables, I played host and interviewed economist and author Erik Brynjolfsson for an Interintellect salon on Automation, Productivity, Work, and the Future.

I also spoke at most (all?) of the top progress conferences this year, including the Foresight Institute’s Vision Weekend, the Future Forum, Breakthrough Dialogue, and Ignite Long Now. I was also on a panel moderated by Ramez Naam at the Breakthrough Science Summit (no relation to the other “Breakthrough”).

Those are just the highlights. You can see all my published interviews and speaking events here.

Social media

My top tweets (500+ likes) of 2022:

(Thanks to Perplexity for making this query easy)

This year I grew my Twitter following by 22%; in August, I crossed 25,000 followers.

I also started doing a weekly digest of my best Twitter content on the blog. If you’re not on Twitter much, subscribe by RSS or email and read those digests instead.

Reminder that I also have a Reddit group (subreddit), Facebook page, and LinkedIn page, if that’s what you’re into.

Events

This year I co-hosted two workshops at UT Austin together with Greg Salmieri.

The first was the Moral Foundations of Progress Studies. For me personally, this discussion brought several issues into sharper focus, and I can already see how it will inform my writing. I’m more clear on different views of well-being now, and how those relate to some of the issues that are discussed around progress—such as the Easterlin paradox (that self-reported happiness and life-satisfaction scores don’t seem to increase with rising wealth over the long term). For the group as a whole, I think it broadened people’s awareness of what alternate moral approaches are out there.

The second was a small, informal, half-day workshop on the concept of “industrial literacy” and how we could promote it in education, for instance, by making the history of progress a part of the curriculum in schools. We brought together a number of educators and edtech entrepreneurs for this. My main takeaway was that there are, broadly speaking, two strategies: (1) Top-down, you can try to change the required curriculum standards, or the standardized tests (e.g., imagine an AP test in the history of technological innovation and economic growth). (2) Bottom-up, you can create materials that you market directly to parents, or (at older ages) the students themselves. Strategy (1) is basically political; strategy (2) is basically a media venture.

These events were good, but one thing I’d like to do in the future is make sure that things like this generate tangible, longer-lasting output that can reach an audience well beyond the event itself.

There were also a few local meetups I hosted or co-hosted in the San Franciso area, and one I spoke at in Boston.

Accolades

I was named to the Vox Future Perfect 50: “The scientists, thinkers, scholars, writers, and activists building a more perfect future.” They did a little feature on me. The list also includes Jennifer Doudna, Max Tegmark, and Max Roser.

Moving to Boston

On a personal note, I’m moving to the Boston area in January. While the move is primarily for my wife’s work, I’m looking forward to the chance to build a new progress network there—the home of MIT and Harvard, of metascience efforts like Convergent Research and New Science, and of many biotech startups. Being on the East Coast will also make it easier to network in DC and New York, and being on Eastern time will make it easier to collaborate with folks in Oxford/London and the rest of the UK and Europe. If you’re in the Boston area, or know people I should meet there, please reach out!

Thank you

2022 was great, and 2023 is positioned to be even better: diving into the actual drafting of my book, Heike coming on board as CEO, and us launching a new institute and set of programs together.

It’s been six years of The Roots of Progress now—just over three of them full-time—and it’s the most meaningful and impactful thing I’ve done in my life so far. I feel like a “quixotic rider cantering in on his own homemade hobby horse” to intercept the world and its problems at an odd angle, and everything I do is possible only because my “eccentric hobbies” seem to resonate with all of you. Thanks for listening, for reading, for commenting, even for arguing, and for all of your support and encouragement.

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/2022-in-review

Podcast: Build for Tomorrow with Jason Feifer

Jason Feifer, one of the creators of Pessimists Archive, did a podcast episode on his show Build for Tomorrow about what people in 1923 thought about the year 2023:

… there was one, one prediction, one prediction that absolutely dominated the conversation, one prediction from one man that led to a national debate, and that prediction was this. In the year 2023, electricity will have made the world so efficient and so prosperous that people will only need to work four hours a day.

I’m one of two guests in this episode, discussing how this did and didn’t come true and why. Listen or read the transcript on the show page.

Links and tweets

I was traveling in December, so this one is covering the last month+.

The Progress Forum

Patrick McKenzie AMA. See also his retrospective on VaccinateCA

Maybe a little bit of naïveté is good? (Eli Dourado). My take: not naïveté, but vision

The false dichotomy between peace and prosperity versus ambition and exploration

Two bits of wisdom about research that are often in tension (Ben Reinhardt)

The Empire State Building and the World Trade Center (Brian Potter), also Part 2

When scientists thought heat was a fluid (Anton Howes)

Progress book recommendations thread (add your recs please!)

Announcements

OpenAI launches ChatGPT (via @sama)

Net energy gain from fusion achieved (@jordanbramble)

The Collegiate Propulsive Lander Challenge: students building self-landing rockets (!)

Nucleate venture fellowship + $2M in prizes for bio founders (via @MichaelRetchin)

Cruise expanding coverage to the full 7x7 of San Francisco, 24/7 (@kvogt)

The Academy of Thought and Industry (who commissioned my progress course) is hiring a liberal arts teacher (@mbateman)

ARIA Research is hiring for many roles (@ilangur)

Links

The world needs processed food (Hannah Ritchie in WIRED, via @tonymmorley)

Why the age of American progress ended (Derek Thompson). See my reactions

Mike Maples interviews Blake Scholl about supersonic flight and Boom

The climate field as an assortment of “tribes” (Nadia Asparouhova)

Warren Weaver’s 1946 guide for Rockefeller grantmakers (via @abiylfoyp)

Homelessness is a housing problem (Jerusalem Demsas in The Atlantic)

Green card backlogs are impossibly long (some measured in centuries!)

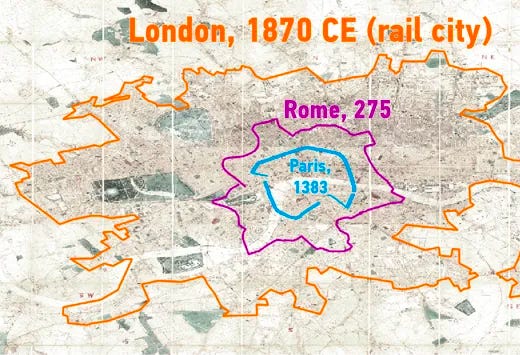

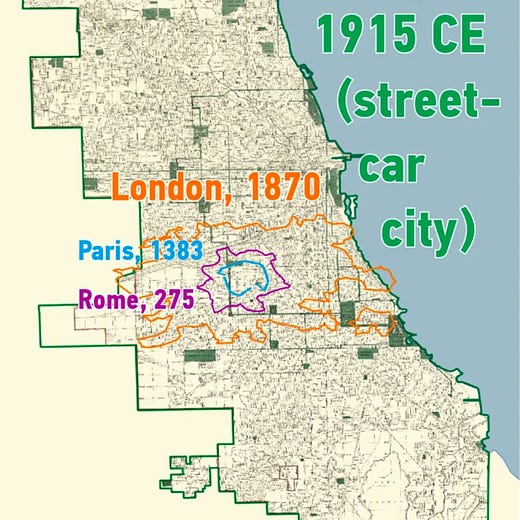

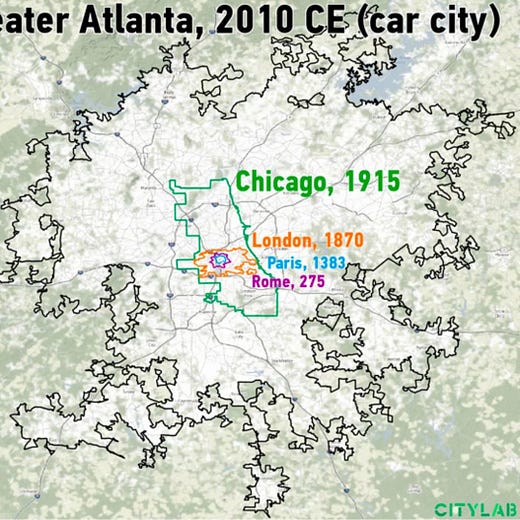

City size is determined by transportation technology (Tomas Pueyo)

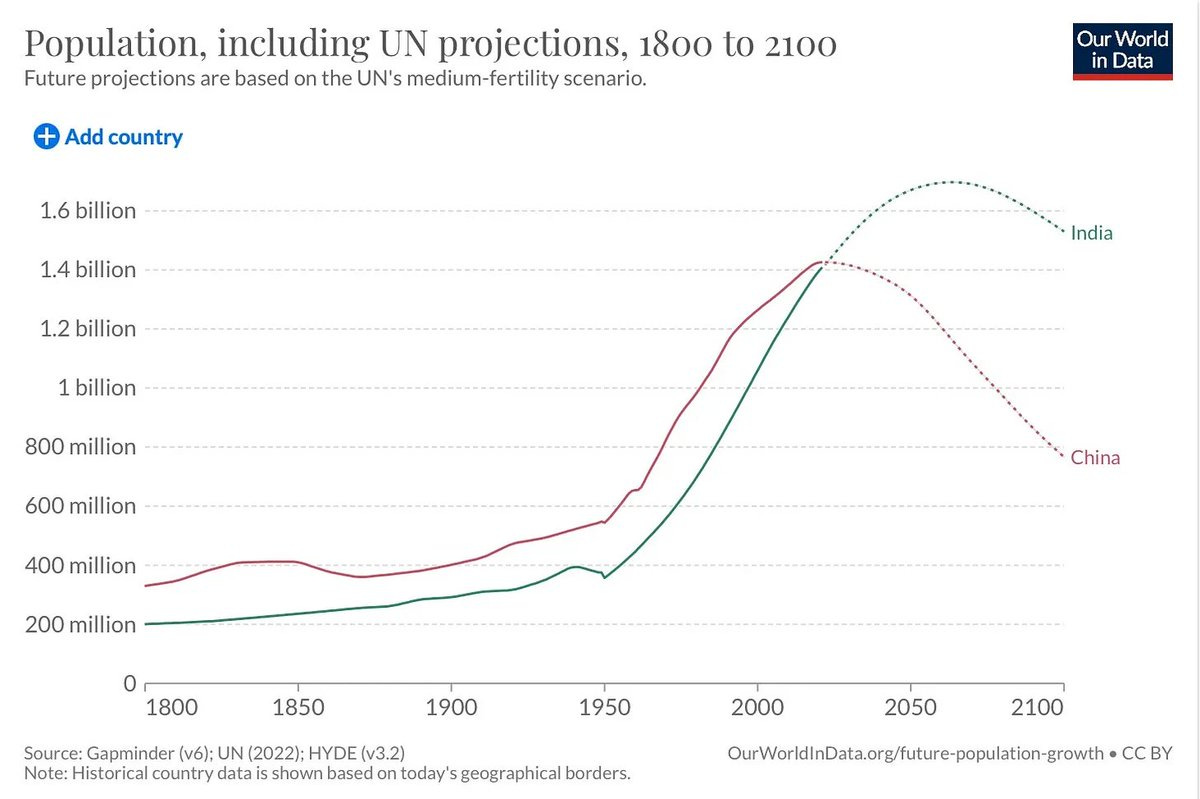

China will depopulate over the next 40 years, while India will add the same number of people as China loses (Shruti Rajagopalan)

Queries

Stories where the good guys have the grand plans / projects? (@TylerAlterman)

Why was the B-21 built in budget while the F-35 was a mess? (@Scholars_Stage)

Book recommendations on modern medicine or public health? (@salonium)

What are the best books/podcasts/people to follow on nuclear energy? (@sriramk)

If we get transformative AI, what will GDP per capita be in 2040? (@elidourado)

Why so few takes on permitting reform from nuclear folks? (@J_Lovering)

Data on European pipeline gas and storage? (@Atomicrod)

Do you have a model of how to approach the problem of progress?

What sports were being played 200 years ago? (@waitbutwhy)

What are some stories that feature getting spare parts for inventing from a junk yard?

Quotes

Mark Twain to Walt Whitman: “What great births you have witnessed!”

Nuclear power construction can require creative solutions—like midget welders

For the first 40 years of photography, handheld cameras were impossible

The spirit of progress, from an 1848 abolitionist pamphlet by Theodore Parker

How communication and transportation networks help eliminate famine

Tweets

Why we stopped using draft horses, despite the romanticism of certain French towns

Sam Altman: in the next decade the marginal cost of intelligence and of energy will trend to zero

Where to, Mr. Chemist? “To a thousand untouched shores” (Du Pont, 1939)

Your can improve your “gut” judgment by priming it with rational thinking

“Scientists may find themselves reporting only successful experiments”

Retweets

“Abundance is the only cure for scarcity… Everything else merely allocates scarcity” (@samhinkie, quoting @patio11)

Converting coal plants into nuclear with small modular reactors. But: Congress ordered the NRC to provide a pathway for new reactors—and they made the process more burdensome (@AlecStapp)

Science has fulfilled Jesus’s message beyond his wildest dreams (@curiouswavefn)

The tin can is underrated (@_brianpotter)

Golden Rice is finally arriving (@stewartbrand)

Why steam turbines are not a good idea for fusion energy (@elidourado)

It’s time to close the book on the amyloid hypothesis (@schrag_matthew)

If you want home values to go up, you don’t want homes to be affordable (@JerusalemDemsas)

The bureaucracy feedback loop, green card edition (@nabeelqu)

How Theodor Engelmann demonstrated that chloroplasts are the site of oxygen production in plants (@strandbergbio)

AI

Photographer uses AI to generate image variations from his own photos (@jonst0kes)

ChatGPT scores 1020 on the SAT (@davidtsong)

LLMs will take either side of an argument depending on the prompt

AI progress has gone exponential and is likely to speed up even further (@zachtratar)

Startlingly effective AI tutoring is coming (@mbateman)

Cheating is a minor issue and the AI cheating arms race doesn’t matter (@mbateman)

Chaining ChatGPT and Midjourney to generate images from a concept (@GuyP)

Charts

It’s a very good time to get a mortgage, taking the long-term view (@charlesjkenny)

Wider...and deeper!

I appreciate the wider look. Still, the IR was indeed born by coal & steam engine, with a distant third place to spinning jenny ( with flying shuttle) and ever more distants (but important!), ie all the rest you mention https://acoup.blog/2022/08/26/collections-why-no-roman-industrial-revolution/

If China or Rome would have been at: no choice but coal + need to pump the coal mines out faster than humans can - they likely would have gone IR. - Agricultural innovation that need only 10% of farm workers did not take off earlier, as farm workers were NO bottleneck before the IR.