What does it mean to “trust science”?

Also: Jason Crawford in Bangalore, August 21 to September 8

I’m on the new social network Threads as @jasoncrawford, follow me there!

In this update:

Full text below, or click any link above to jump to an individual post on the blog. If this digest gets cut off in your email, click the headline above to read it on the web.

Bangalore, August 21 to September 8

I’ll be in Bangalore for three weeks starting next week (August 21–September 8). I’d love to meet anyone interested in the progress movement, and I’m looking into organizing a progress meetup.

If you’d like to meet me and/or join a meetup—or especially if you could help host the meetup—please share your info with me via this brief form. Thanks a lot!

What does it mean to “trust science”?: Science asks you not to trust, but to think

And this, my children, is why we do not say things like “I believe in science”. I mean, don’t get me wrong, science definitely exists—I’ve seen it. But not everything that calls itself science is science, and even good science sometimes gets wrong results. –Megan McArdle

Should we “trust science” or “believe in science”?

I think this is a fuzzy idea that we would do well to make clear and precise. What does it mean to “trust science?”

Does it mean “trust scientists”? Which scientists? They disagree, often vehemently. Which statements of theirs? Surely not all of them; scientists do not speak ex cathedra for “Science.”

Does it mean “trust scientific institutions”? Again, which ones?

Does it mean “trust scientific papers”? Any one paper can be wrong in its conclusions or even its methods. The study itself could have been mistaken, or the writeup might not reflect the study.

And it certainly can’t mean “trust science news,” which is notoriously inaccurate.

More charitably, it could mean “trust the scientific process,” if that is properly understood to mean not some rigid Scientific Method but a rational process of observation, measurement, evidence, logic, debate, and iterative revision of concepts and theories. Even in that case, though, what we should trust is not the particular output of the scientific process at any given time. It can make wrong turns. Instead, we should trust that it will find the truth eventually, and that it is our best and only method for doing so.

The motto of science is not “trust us.” (!) The true motto of science is the opposite. It is that of the Royal Society: nullius in verba, or roughly: “take no one’s word.”

There is no capital-S Science—a new authority to substitute for God or King. There is only science, which is nothing more or less than the human faculty of reason exercised deliberately, systematically, methodically, meticulously to discover general knowledge about the world.

So when someone laments a lack of “trust” in science today, what do they mean? Do they mean placing religion over science, faith over reason? Do they mean the growing distrust of elites and institutions, a sort of folksy populism that dismisses education and expertise in general? Or do they mean “you have to follow my favored politician / political program, because Science”? (That’s the one to watch out for. Physics, chemistry and biology can point out problems, but we need history, economics and philosophy to solve them.)

Anyway, here’s to science—the system that asks you not to trust, but to think.

Adapted from a 2019 Twitter thread.

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/what-does-it-mean-to-trust-science

Links digest, 2023-08-17: Cloud seeding, robotic sculptors, and rogue planets

Opportunities

News & announcements

Waymo and Cruise have been approved to operate robotaxis in San Francisco

Rainmaker launches to “end global water scarcity and terraform Earth”

Podcasts

Dwarkesh Patel interviews Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic (via @dwarkesh_sp). “Dario is hilarious & has fascinating takes on what these models are doing, why they scale so well, & what it will take to align them”

Links

Monumental Labs is building “AI-enabled robotic stone carving factories” to “create cities with the splendor of Florence, Paris, or Beaux-Arts New York, at a fraction of the cost.” Here’s a demo (via @devonzuegel). They are hiring stone carvers (who are still required for fine details and finishing)

The AI License Raj: AI is facing serious bureaucratic hurdles in getting adopted (by @WillRinehart)

“My personal history as a metascience venture capitalist” (by @stuartbuck1)

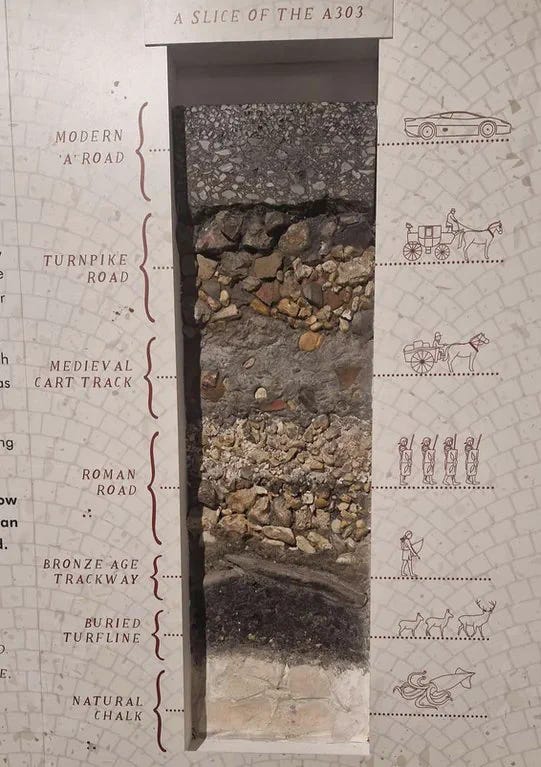

A303 in Hampshire, England, passes through Stonehenge and part of the ancient Roman Fosse Way is included in it (via @Rainmaker1973)

Social media

If you got over-excited about LK-99, worth recalibrating your priors. But if you correctly predicted no RTS, there’s really no need to gloat. Related: LK99 demonstrated that the scientific community is perfectly capable of doing a peer review via arXiv and social media tools

“NuScale started working toward regulatory approval in 2008. In 2020, when it received a design approval for its reactor, the company said the regulatory process had cost half a billion dollars, and that it had provided about 2 million pages of supporting documents to the NRC.” Related, my book review on why nuclear power flopped

What it means to endlessly, tirelessly campaign for your idea

Maybe “balance” is an unhappy person’s idea of a happy life. Happy people seem fine being unbalanced

Alexander Fleming originally called penicillin “mould juice”

Quotes

Trying a new format where I put the full quotes inline. (Emphasis added.) Links go to social media so you can easily share. Let me know what you think:

The invention of the history of ideas (Peter Watson, Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud)

The first person to conceive of intellectual history was, perhaps, Francis Bacon (1561–1626). He certainly argued that the most interesting form of history is the history of ideas, that without taking into account the dominating ideas of any age, ‘history is blind’.

Why automobiles were better than horses—from someone who lived through the transition (David McCullough, The Wright Brothers)

Amos Root bubbled with enthusiasm and a constant desire to “see the wheels go round.” He loved clocks, windmills, bicycles, machines of all kinds, and especially his Oldsmobile Runabout. Seldom was he happier than when out on the road in it and in all seasons. “While I like horses in a certain way [he wrote], I do not enjoy caring for them. I do not like the smell of the stables. I do not like to be obliged to clean a horse every morning, and I do not like to hitch one up in winter. … It takes time to hitch up a horse; but the auto is ready to start off in an instant. It is never tired; it gets there quicker than any horse can possibly do.” As for the Oldsmobile, he liked to say, at $350 it cost less than a horse and carriage.

Even kings and emperors suffered from terrible road conditions, as late as the 18th century (Richard Bulliet, The Wheel)

Until new experiments with road building began to bear fruit in the mid-nineteenth century, the surfaces beneath the carriage wheels remained rutted, muddy, and poorly paved—if paved at all. This was particularly true in the countryside, but miserable roads existed even in major cities. In 1703, for example, during a trip south from London to Petworth, fifty miles away, the carriage carrying the Habsburg emperor Charles VI overturned twelve times on the road. And a half century later, Mile End Road, the major thoroughfare leading east from the entrance to the City of London at Aldgate, was described as “a stagnant lake of deep mud from Whitechapel to Stratford,” a distance of four miles.

Mises against stability (Daniel Stedman Jones, Masters of the Universe)

Like Popper, Mises saw a similarity between the bureaucratic mentality and Plato’s utopia, in which the large majority of the ruled served the rulers. He thought that “all later utopians who shaped the blueprints of their earthly paradises according to Plato’s example in the same way believed in the immutability of human affairs.” He went on, Bureaucratization is necessarily rigid because it involves the observation of established rules and practices. But in social life rigidity amounts to petrification and death. It is a very significant fact that stability and security are the most cherished slogans of present-day “reformers.” If primitive men had adopted the principle of stability, they would long since have been wiped out by beasts of prey and microbes.

What it’s like to try to redirect the lava flow of an erupting volcano (Eldfell, Iceland, 1973) (John McPhee, The Control of Nature)

During the eruption, when the pumping crews first tried to get up onto the lava they found that a crust as thin as two inches was enough to support a person and also provide insulation from the heat—just a couple of inches of hard rock resting like pond ice upon the molten fathoms. As the crews hauled and heaved at hoses, nozzle tripods, and sections of pipe, they learned that it was best not to stand still. Often, they marched in place. Even so, their boots sometimes burst into flame.

Charts

US utilization-adjusted TFP has experienced 3 consecutive quarters of decline and is now below the level it was at in 2019Q4, before the pandemic. This is bad (via @elidourado)

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/links-digest-2023-08-17

The word science come from the Latin “to know.” Science is the means of learning about our world. The scientific method is a series of steps followed by scientists studying some aspect of nature. It begins with a question whose answer is unknown. A reasonable answer to this question is generated based on what is known. This educated guess is a hypothesis. From there, an experiment is designed and performed to try to answer the question. Alternatively, observations may be made over time. Based on the results of the experiment or observations, the hypothesis may be rejected or validated. Then the experiment is critiqued and repeated by other scientists to add to the evidence. I think the most important step of this process is the last; scientists openly discussing and debating each other’s methods and results.

Some scientific questions asked today are difficult to answer using the scientific method. Questions regarding climate are especially difficult to answer because scientists cannot perform experiments in which they can control all of the variables that impact climate. Instead, climate scientists use observations and models to see patterns and make predictions. These are unreliable methods for understanding why climate changes, because the data is incomplete and the outcomes of modeling depend on numerous variables. Additionally, most funding for this research comes from the government, whose leaders are pushing climate policies that reduce fossil fuel use. Furthermore, open discussion and debate over climate is virtually nonexistent, limiting public access to opposing interpretations of these observations and models. As a result, we have a society of climate change “believers” and climate change “ deniers.”

Scientists are skeptics. When they get a result, they do not simply believe or trust the results. Rather, they analyze and share their methods and results, debate with other scientists, and repeat their experiments to get to the truth.

Science is the new magic. I have no idea if this is by design, but the social structure we live in supports this.