What I've been reading, November 2023

Also: Podcast interview with Giuliano Giacaglia

Following the successful launch of The Roots of Progress Fellowship, we are now fundraising to support and expand the program in 2024 and beyond. View our full fundraising pitch and see how to donate here.

In this update:

Full text below, or click any link above to jump to an individual post on the blog. If this digest gets cut off in your email, click the headline above to read it on the web.

What I've been reading, November 2023

A ~monthly feature. Recent blog posts and news stories are generally omitted; you can find them in my links digests. All emphasis in bold in the quotes below was added by me.

Books

Finished Lynn White, Medieval Technology and Social Change (1962). Last time I talked about the stirrup thing. The second part of the book is about the introduction of the heavy plow in agriculture, and how it enabled the shift to a three-field crop rotation. Among other things, this provided more protein in the European diet, which made for a healthier population. The third part is a survey of medieval power mechanisms, including water mills, crank shafts, and clock escapements. Very interesting overall, perhaps a bit dry and technical for casual readers though. Note also that since it is from the ’60s it is not up to date with the latest research.

Also finished Ian Tregillis’s The Alchemy Wars. I can now definitely recommend this sci-fi/fantasy trilogy, even if the cast of characters and the way the conflict unfolded isn’t exactly how I would have written it myself.

Browsed Derek J. de Solla Price, Science since Babylon (1961), while preparing for a talk. Some very interesting charts such as this:

New on my reading list:

Venkatesh Narayanamurti and Toluwalogo Odumosu, Cycles of Invention and Discovery: Rethinking the Endless Frontier (2016), and Venkatesh Narayanamurti and Jeffrey Tsao, The Genesis of Technoscientific Revolutions: Rethinking the Nature and Nurture of Research (2021). These have actually been on my list for a while, but got bumped back up after meeting Venky and Jeff at a recent workshop on metascience. (The latter book is required reading at Speculative Technologies.)

Also mentioned at the workshop: B. Zorina Khan, Inventing Ideas: Patents, Prizes, and the Knowledge Economy (2020); and A Michael Noll and Michael Geselowitz, Bell Labs Memoirs: Voices of Innovation (2011).

Also:

Pedro Domingos, The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World (2015)

Robert Martello, Midnight Ride, Industrial Dawn: Paul Revere and the Growth of American Enterprise (2010)

Jessie Singer, There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster—Who Profits and Who Pays the Price (2022)

Ursula Le Guin, The Dispossessed (1974) (sci-fi)

Articles

Ray Kurzweil, “The Law of Accelerating Returns” (2001). Kurzweil strikes me as a grand theorist but not a careful scholar—a risky combination. For instance, he writes: “Homo sapiens evolved in a few hundred thousand years. Early stages of technology—the wheel, fire, stone tools—took tens of thousands of years to evolve and be widely deployed.” Stone tools, fire, and the wheel are often depicted in cartoons featuring cavemen. But stone tools evolved over millions of years; the controlled use of fire is something like several hundred thousand years old; and both predate Homo sapiens. The wheel came much later, well after agriculture and settled society. Details like this are a warning to tread carefully.

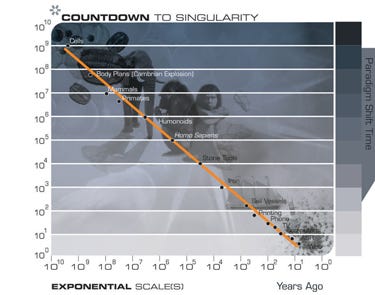

That said, I was interested to read this essay because I am starting to see the truth and significance of its core idea: that human progress accelerates over time, following a super-exponential curve. This phenomenon has been documented more broadly in the economics literature, such as by Jones and Romer (2010), who refer to “accelerating growth” as one of the key stylized facts that growth models should attempt to explain.

I have described acceleration as resulting from the compounding of multiple feedback loops: increases in wealth, population, science, markets, institutions, and technology allow us to invent more, improve institutions, expand markets, advance science, grow population, accumulate wealth, etc. Kurzweil sees the phenomenon as not merely technological, but biological—a feature of evolution as such (and he sees technological evolution as simply a continuation of biological evolution by more efficient means). In his telling, as evolution progresses, it sometimes evolves better mechanisms for evolving. This is a very intruiging idea, but he doesn’t argue it with any rigor or present much evidence for it, and I don’t know enough about biology or evolution to evaluate it. He mentions “cells” as the “first step” in evolution, and then refers to “the subsequent emergence of DNA” (but wasn’t DNA present from the origins of life?) He indicates that evolution sped up during the Cambrian Explosion, and credits this to “setting the ‘designs’ of animal body plans”, but doesn’t elaborate on the causal connection except to say that this “allowed rapid evolutionary development of other body organs, such as the brain.” Presumably sexual reproduction should be a major event in this story, since it allows for more variation through genetic recombination, but he doesn’t mention it. So, it’s very unclear to me what to make of this story (although if it’s right, it would extend the “accelerating progress” pattern backwards by more than three billion years).

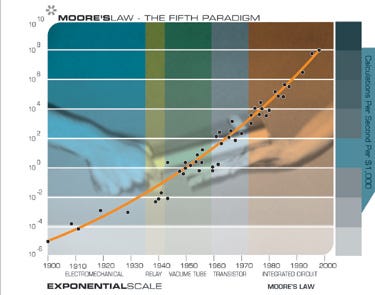

Grand theories aside, I was very interested in his analysis of computing power. He plotted the computing speed per dollar of dozens of devices, all the way from late 19th-century mechanical calculators through early 21st-century microprocessors, and claims to have found a increasing cost-performance curve running through five generations of computing technology: purely mechanical, electromechanical, vacuum tube, transistor, and integrated circuit. Moore’s Law is only the fifth and most recent segment of this much longer trend, one exponential portion of an overall super-exponential curve:

I’d like to check the data and sources on this one, but it’s a very intriguing pattern.

The full essay is very long and covers many not-super-well-connected topics, which I don’t have time to comment on; the core idea is in this 2004 Edge question, but doesn’t contain all the most interesting details (such as the computing trends just mentioned).

The same accelerating curve, and the same basic explanation based on feedback loops, seems to be the gist of David Roodman, “Modeling the Human Trajectory” (2020), which I have only skimmed but plan to return to.

Others:

Deirdre N. McCloskey reviews Acemoglu and Johnson’s Power and Progress (2023). If you know anything about the book, and anything about McCloskey, you won’t be surprised that she is critical:

The invisible hand of human creativity and innovation, in the authors’ analysis, requires the wise guidance of the state. … This is a perspective many voters increasingly agree with—and politicians from Elizabeth Warren to Marco Rubio. We are children, bad children (viewed from the right) or sad children (viewed from the left). Bad or sad, as children we need to be taken in hand. Messrs. Acemoglu and Johnson warmly admire the U.S. Progressive Movement of the late 19th century as a model for their statism: experts taking child‐citizens in hand.

Robert Tracinski, “We Are All Philosophers Now” and “The Dilemma of Choice” (2023). Modernity has replaced a narrow, limited set of social roles and life choices with a smorgasbord of options. This is liberating, but the price of the freedom of choice is the responsibility of choice, which is now everyone’s to bear. Not everyone is happy about this. Rob’s pithy summary: “If Socrates said that the unexamined life is not worth living, well, now it’s not really an option.”

Virginia Postrel, “What ails American culture?” (2023). On similar themes:

Human beings need to feel purpose and meaning in their lives. But I am not entirely sure that the current discontent is a product of material abundance, that people did not feel similar discontent in the past, or that the “economic problem” loomed so large in the past that it dwarfed all other problems.

Ben Landau-Taylor, “The Vocabulary Of Power” (2023). “Power” can mean many things; here are four more precise terms. Not only will this help clarify your concepts, it will also fulfill your daily quota of thinking about the Roman Empire.

Tanner Greer, “Where Have All the Great Works Gone?” (2021):

Spengler … repeatedly describes Tolstoy (d. 1910), Ibsen (d. 1906), Nietzsche (d. 1900), Hertz (d. 1894), Dostoevsky (d. 1881), Marx (d. 1883), and Maxwell (1879) as figures of defining “world-historical” importance… Spengler began writing Decline of the West in 1914. Tolstoy was only four years dead when Spengler started his book; Marx was only 30 years deceased. … Is there anyone who died in the last decade you could make that sort of claim for? How about for the last two decades? The last three?

Gideon Lewis-Kraus, “They Studied Dishonesty. Was Their Work a Lie?” (2023). A case study of scientific fraud.

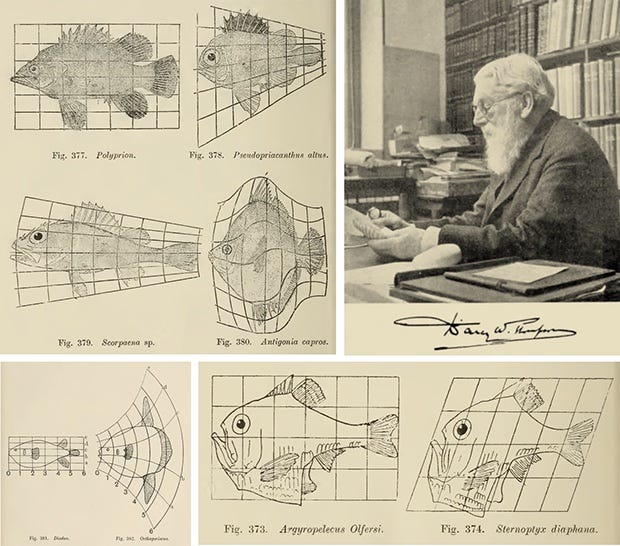

Stephen Wolfram, “Are All Fish the Same Shape If You Stretch Them? The Victorian Tale of On Growth and Form” (2017) I just thought this idea was kind of hilarious:

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/reading-2023-11

Podcast interview with Giuliano Giacaglia

I went on Giuliano Giacaglia’s podcast to discuss stagnation, how progress happens, progress in energy, nuclear energy, progress in agriculture, and where inventions are created.

I think what really made me come around to this point of view is studying the history of progress and basically deciding that it’s not about bits versus atoms. It’s about the fact that we’ve had progress in only bits when we really should have had progress in both bits and atoms at the same time bits, atoms, cells and joules…

We actually can make progress on all fronts at once. And the proof of this is really the late 19th and early 20th century. In the 50 years from 1870 to 1920, just to pick a relatively arbitrary time period, we had, by my count, approximately five major revolutions or big breakthroughs on five fronts.

Timestamps:

00:00 Instead of flying cars, we got 140 characters

06:30 Bursts of progress

09:47 Progress in energy

19:42 Nuclear energy and lack of progress

27:57 Progress in agriculture

37:50 Food prices

44:34 Where are inventions created?

1:02:17 The Roots of Progress Fellowship

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/podcast-interview-with-giuliano-giacaglia

Links digest, 2023-11-07: Techno-optimism and more

Again I’ve been delayed in putting this out by travel etc., so it’s a longer one with links from the last month or so. Feel free to skim and skip around:

On the Progress Forum

Radical Energy Abundance, by Casey Handmer

FAA’s safety philosophy and progress in personal aviation, by Eli Dourado

Where I have landed on “ideas getting harder to find”, in a nutshell, by me

Getting the Conditions Right: Progress in Weather Forecasting, by Jeremy

Something Is Getting Harder To Find But It’s Not Ideas, by Maxwell and Connor Tabarrok. (“Clever, wonderful, and entertaining presentation of our paper,” says @ChadJonesEcon.) Also, Did Medieval Peasants Have More Vacation Time Than Us?

Today’s backwater, tomorrow’s superstar, by Connor O’Brien. Also, How does a society hedge its bets? and Industrial policy needs immigration reform

Schadenfreude versus optimism in drug development, by Alex Telford. Also, Should the UK embrace its role as an exporter of talent and ideas?

Health Insurance Pricing: Battling the snake-heads of Hydra, by Tina Marsh Dalton

Address to a Unitarian Universalist congregation on my Heritage, by Matt Ritter

Other work from the Roots of Progress fellows

American Power Was Built on Cost Overruns, by @Madeline_Zimm. (IMO, the biggest risk of running over schedule/budget is that your project will get canceled. If it doesn’t, people will judge it based on what it accomplished and not care about anything else. Lots of great things were delivered late and over budget)

The Golden Age of Aerospace, by Brian Balkus

How to Imbue the Basic Models of Biology With a Positive Vision of the Future, by @MTabarrok

Concepts of health and disease as a barrier to progress, by @Atelfo

Follow all the ROP fellow Twitter accounts via this list.

Opportunities

Arc Institute announces a new call for applications for Core Investigators, “scientific leaders who are empowered to tackle curiosity driven research” (via @arcinstitute). Their new building officially opened recently

Speculative Technologies launches the “Brains” Coordinated Research Accelerator “to help people with ambitious research ideas refine them and find a place to execute on them in government organizations, nonprofits, and beyond” (via @Spec__Tech)

Convergent Research is hiring a Launch Manager to “work closely with each new FRO as it starts as well as the whole CR team” (via @AGamick)

The World’s Fair Co. is hiring a Chief of Staff to help scale their projects (via @camwiese)

OpenAI is hiring for “a new quantitative & evidence-driven approach to AI safety.” Related, their $10M AI Safety fund

Our World in Data is hiring a Communications & Outreach Manager (via @MaxCRoser)

A new biology lab in St. Louis for any “renegade scientist who wants to find a way to just do the science without starting a company” (via @BenAnderson421)

Announcements

The Vesuvius Challenge has read the first word from an unopened Herculaneum scroll (via @natfriedman). The word is “πορφυρας” which means “purple dye” or “cloths of purple.” (Why would purple be a topic of interest? In the ancient world, purple dye was made from mollusk mucus. It took roughly 9,000 mollusks per gram of this dye, making it labor-intensive, and therefore expensive, and therefore high-status—reserved only for royalty.)

Homeworld publishes over 50 proposals from a program focused on protein engineering (via @HomeworldBio)

A student team at Berkeley won the first Lander Challenge prize for reusable rockets

News

First malaria vaccine slashes early childhood mortality: Huge analysis of RTS,S in Africa shows it decreased toddler deaths by 13% (via @michael_nielsen). Related, Alex Tabarrok makes the case for rapid malaria vaccination

More carbon than expected and an abundance of water were found in the 4.5-billion-year-old asteroid sample returned to Earth by OSIRIS-REx (via @NASA)

Swiss Re says that “Waymo’s driverless vehicles file 76% fewer property damage claims compared to human-driven cars” (via @devonzuegel). And Cruise publishes a white paper claiming their AVs “outperform humans in a comparable driving environment” (via @kvogt). After this was published, however, a Cruise car was involved in an accident in SF; California suspended Cruise’s license, and then Cruise decided to pause operations nationwide. I don’t know whether AVs are truly safer than human drivers yet, but I am confident they will get there, because every time we solve a problem like this, we can solve it for good. AVs never forget their training, while every day first-time human drivers are out on the road.

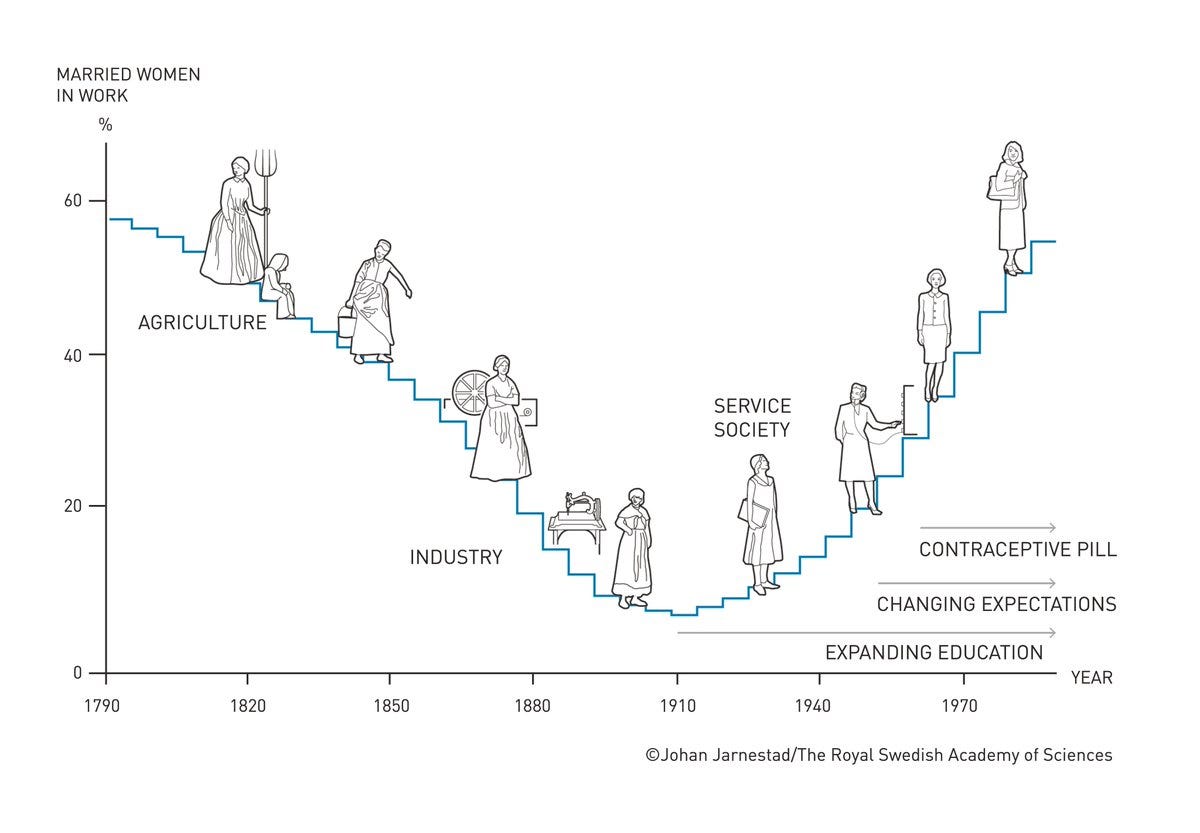

Claudia Goldin won the economics Nobel “for having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes.” Her work “showed that female participation in the labour market did not have an upward trend over a 200 year period, but instead forms a U-shaped curve” (via @NobelPrize)

Techno-optimism

Marc Andreessen publishes “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto” (via @pmarca)

Stewart Brand calls it “clarifying and self-consistent” but “incomplete”

Ben Reinhardt responds with an annotated copy (via @Ben_Reinhardt)

Virginia Postrel calls it a Rorschach test

Matt Yglesias says it commits a fallacy

Ezra Klein calls it “reactionary futurism”

Jim Pethokoukis says it’s basic economics

Noah Smith gives his thoughts

Chris Albon tries to explain why Andreessen mentioned “tech ethics” in a section titled “The Enemy”

More discussion on the Progress Forum. I have not written a response yet, but see my previous writing on different forms of optimism and on “solutionism” as a third way between complacent optimism and defeatist pessimism.

Papers

An Economic View of Corporate Social Impact: “We find that consumer surplus is the primary component of social impact (dwarfing profits, worker surplus, and externalities)” (via @dylanmatt)

One Giant Leap: Emancipation and Aggregate Economic Gains: “We re-characterize American slavery as inefficient, whereby emancipation generated substantial aggregate economic gains” (via @Rick__Hornbeck)

Podcasts

Introducing: Age of Miracles (via @packyM). “Each season, we’re diving into one frontier industry that will shape our superabundant future.” Season 1 is on nuclear, with @juliadewahl (who was inspired in part by my nuclear talk)

Bret Kugelmass interiews Eli Dourado for Titans of Nuclear, self-recommending (via @elidourado)

Saloni Dattani on “Hear This Idea” talking about the history of malaria (via @salonium)

Lant Pritchett on economic growth, charter cities, labor mobility, and state capability with the Charter Cities Institute (via @kurtislockhart)

Dwarkesh interviews Grant Sanderson of 3blue1brown (via @dwarkesh_sp)

Articles

Ben Southwood says induced demand is fake but also sometimes roads are bad

“Unlike other antivenom treatments which are specific to a type of snake, varespladib methyl is capable of curing a broad spectrum of bites from different snake species. This means that the infamous line found in older first-aid manuals for treating snake bites (‘If possible, catch the snake…’ – so that the doctors can identify which antivenom to give), can now thankfully be ignored.” Varespladib methyl is the molecule of the month

Micro-essays from me

“What is progress?” I don’t think there’s much difficulty in the concept of “progress,” it just means a movement forward along some path. The difficulty is in: which path, toward what end? There’s also not much difficulty in understanding what progress means in science, technology, or the economy: it is an advance in our knowledge and capabilities, our ability to understand and manipulate/control the world. The difficulty is in defining human progress, and understanding how it relates to the other forms. In general, I would say that human progress is anything that helps people live better lives: longer, healthier, happier lives; lives with more choice and opportunity; lives of thriving and flourishing. (Threads)

When we think about “state capacity”, we should make a distinction between state effectiveness and state scope. If a given function (building infrastructure, responding to pandemics, etc.) is a government function, then it is a government responsibility, and it’s important for government to be good and effective at that thing, and not be interfered with. But separately we can debate which functions are good ones to give to the government and which are better private. I find that the concept of “capacity” can blur these distinctions. (Twitter, Threads)

Queries

John Carmack’s book challenge: “I appreciate that there are many people who roll their eyes at my optimistic-libertarian-technological-triumphalist take on things … suggest a book for me to read that you think will challenge my worldview”

Historical examples of technological bottlenecks and key risks? Related, examples of small differences making the difference in a technology’s ability to get out of R&D and into the real world?

How much of “we don’t build beautiful buildings anymore” comes down to local building restrictions?

Well-known examples of externalities (positive and negative, solved and unsolved)?

Social media

Cheap, nimble robots are coming soon. Related, Amazon has started testing these human-like robots in one of its Washington-based warehouses

“Starlink satellites orbit at around 550 km of altitude. What if we could build satellites that could orbit at half that altitude? Cutting transmission distance in half would mean cutting power requirements for handsets by a factor of 4. There’s enough atmospheric drag at 250 km that satellites there will deorbit within days. How do you build a satellite that can stay there indefinitely? Air-breathing propulsion” (@elidourado)

“Most things with a combustion engine will be replaced with a battery in years to come. … Tipping point economics will be different for each use case. Currently: lawnmowers”

When pineapples represented the height of luxury. “We are surrounded by things … which have become normal or even boring but which, to people in the past, were miraculous and delightful”

“22% of the children born in 1950 died before they were five years old. Since then, child mortality has fallen to 3.7%. Our animation shows this wasn’t just due to progress in a few countries. People around the world have achieved improvements” (@MaxCRoser)

“Went to the pharmacy—naturally many people are coughing in the queue. But there’s no airflow from outside, no air filtration system, & no air purifiers on the ground cleaning the air so people don’t infect one another. Future generations will look back and think we were mad!” (@robertwiblin) Like 19th-century hospitals, where you were more likely to catch something than to be cured. Related, “every cold and flu is a policy failure! If we were smart we could scale up far-UVC lamps and put an end to respiratory disease”

Virginia Postrel clarifies some points about looms and Luddites

“You can work safely” is a better motto than “Safety is our top priority”

Related, good illustration of how un-safety-conscious people were 100 years ago

“Homelessness” is the most serious problem according to San Franciscans, and “too much construction” is the least. Does that give anybody any ideas?

Large-scale immigration to Japan was spearheaded by Abe to make up for the low birth rate

“There should be a test like the series 65 that just gives you permission to access any pharmaceuticals you want. Accredited ingestor status” (via @devonzuegel)

“In the 19th Century, the only planning requirement infrastructure had to go through was a committee of five MPs, who couldn’t own land in the route, represent a constituency there, or have shares in a railway proposal they considered” (@bswud) Related: “If we tried to build the Panama Canal today the plan would never pass an environmental impact review process” (@rasheedguo)

“In America’s history, we see celebration of competent, principled and strong men. Not only did we cherish it, we invested heavily in enabling more” (@codyaims)

“When Bell Labs announced the transistor – arguably the most important invention of the modern age – the New York Times buried the story on page 46. Don’t get discouraged if people don’t understand the value of what you’re working on” (@sethbannon)

“The Roman Empire produced several million square meters of polished marble slabs, this was possible because it invented and used water-powered stone-cutting machines” (@lefineder)

“Computer vision has been solved” (@_vztu)

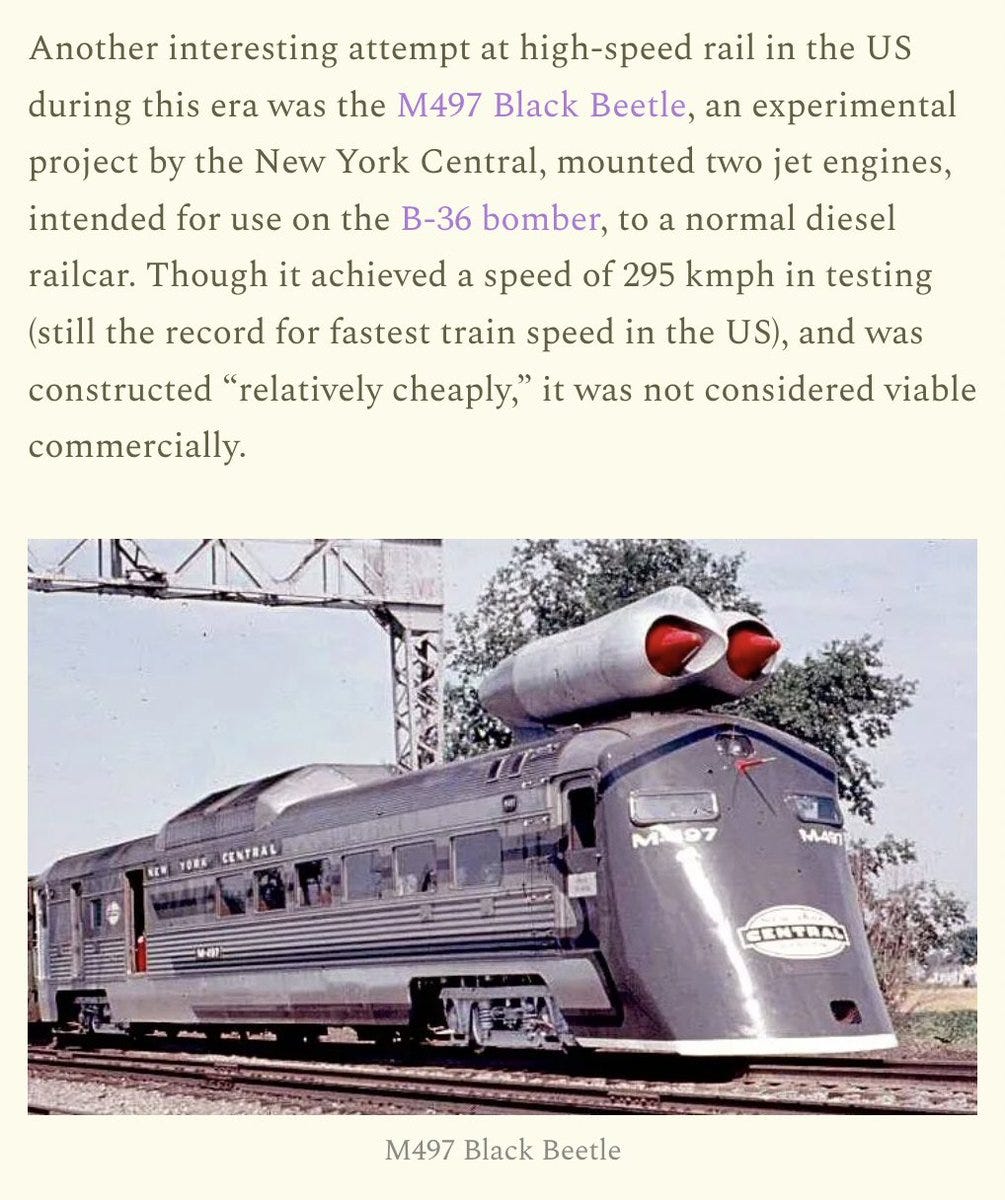

The record for fastest train speed in the US was achieved by mounting two jet engines from a B-36 bomber to a diesel railcar (via @AlecStapp)

“If we solve immortality by, say, 2050, then nearly all of us, anyone still alive by then, are effectively children. We might live 1000 years. Meet our great^20 grandchildren. Journey to the stars.” (@CJHandmer)

Quotes

From Whole Earth Discipline by @stewartbrand:

Science is the only news.

When you scan through a newspaper or magazine, all the human interest stuff is the same old he-said-she-said, the politics and economics the same sorry cyclic dramas, the fashions a pathetic illusion of newness, and even the technology is predictable if you know the science.

Human nature doesn’t change much; science does, and the change accrues, altering the world irreversibly.

“Peanut butter killed formal rulemaking”

The United States Department of Agriculture tried this when it was about to issue a rule regarding the minimum peanut content in peanut butter. Advocates wanted it to be at least 90 percent peanuts, manufacturers wanted to require only 87 percent peanuts, and adjudicating that 3 percent difference under the formal rulemaking process took the Food and Drug Administration twelve years of the 1960s and 1970s. The case went almost all the way to the Supreme Court, and the oral hearing alone took twenty weeks and produced a 7736-page transcript. (The advocates ultimately prevailed.) Since then, when Congress writes laws, it usually avoids the words “on the record” when it comes to rulemaking, leaving agencies the option to choose the informal “notice and comment” process. Unsurprisingly, it’s chosen every time. Peanut butter killed formal rulemaking.

(Although @JamesBroughel comments: “Actually, the real reason agencies don’t use formal rulemaking is a Supreme Court case called United States v. Florida East Coast Railway, where the court ruled agencies may use informal notice-and-comment rulemaking in all but a very limited set of circumstances.”)

Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Committee, Inc. v. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 1971:

These cases are only the beginning of what promises to become a flood of new litigation — litigation seeking judicial assistance in protecting our natural environment. Several recently enacted statutes attest to the commitment of the Government to control, at long last, the destructive engine of material “progress.”

(Brought back to mind via Jim Pethokoukis via Alex Tabarrok.)

“The leadership of Operation Warp Speed made a lot of personal sacrifices to deliver a safe and effective vaccine in record time. And they get almost no credit” (@AlecStapp):

When Slaoui had his job interview on May 11, he minced no words. “All I want to do is make a vaccine that helps our country and the world, he said. “I’m not going to be afraid to break things. I have no political ambition.” If he had to hold meetings just to placate people, he was out. And if there was any political interference, he would resign on the spot. The other five candidates all expressed doubt about having a vaccine by the end of 2020. Slaoui alone said he could do it. He got the job. He resigned from Moderna’s board and sold all his stock in the company, knowing that he was likely forfeiting a fortune. He also decided he wouldn’t take a paycheck for overseeing the project.

Policies as “organizational scar tissue” (from Jason Fried):

Many policies are organizational scar tissue-codified overreactions to situations that are unlikely to happen again.

The second something goes wrong, the natural tendency is to create a policy. “Someone’s wearing shorts!? We need a dress code!” No, you don’t. You just need to tell John not to wear shorts again.

Policies are organizational scar tissue. They are codified overreactions to situations that are unlikely to happen again. They are collective punishment for the misdeeds of an individual.

This is how bureaucracies are born. No one sets out to create a bureaucracy. They sneak up on companies slowly. They are created one policy -one scar -at a time.

So don’t scar on the first cut. Don’t create a policy because one person did something wrong once. Policies are only meant for situations that come up over and over again.

“I think about this list from @elidourado a lot. Progress is a policy choice.” (@AlecStapp, originally from City Journal):

If we can’t counterbalance the supply shock in every granular manifestation, we can at least take action to boost productivity and aggregate supply. Macroeconomic textbooks don’t focus on this policy lever because they assume that the supply side of the economy is already optimized. Yet it is manifestly evident that American society is not maximizing its productivity. If we wanted to raise American productivity, for example, we could simplify geothermal permitting, deregulate advanced meltdown-proof nuclear reactors, make it easier to build transmission lines, figure out why high-speed rail is so expensive, fix permitting generally, abolish the Jones Act, automate our ports, allow drones to operate autonomously, legalize supersonic flight over land, reduce occupational-licensing requirements, train more medical workers, build more hospitals, revamp our pandemic-response institutions, simplify drug approvals, deregulate land use to allow denser housing and mixed-use neighborhoods, allow more immigration, cancel inefficient programs, restrict cost-plus procurement contracts in favor of more effective methods, end appropriations based on job creation, avoid political direction of scientific research, and instill urgency in grantmaking.

Charts

The original chart that inspired Steve Jobs to liken the computer to “a bicycle for the mind” (via Heike Larson):

“In late 17th century England the professional class was almost wholly literate, the latter spread of literacy was just a matter of all the other classes joining them” (@lefineder). Note in particular the growth of literacy among artisans ~1600–1700s. Part of what made the Industrial Revolution was the combination of abstract knowledge and craft skill. George Stephenson learned to read so that he could study steam engines, then invented the locomotive:

Agricultural land efficiency (via @HumanProgress):

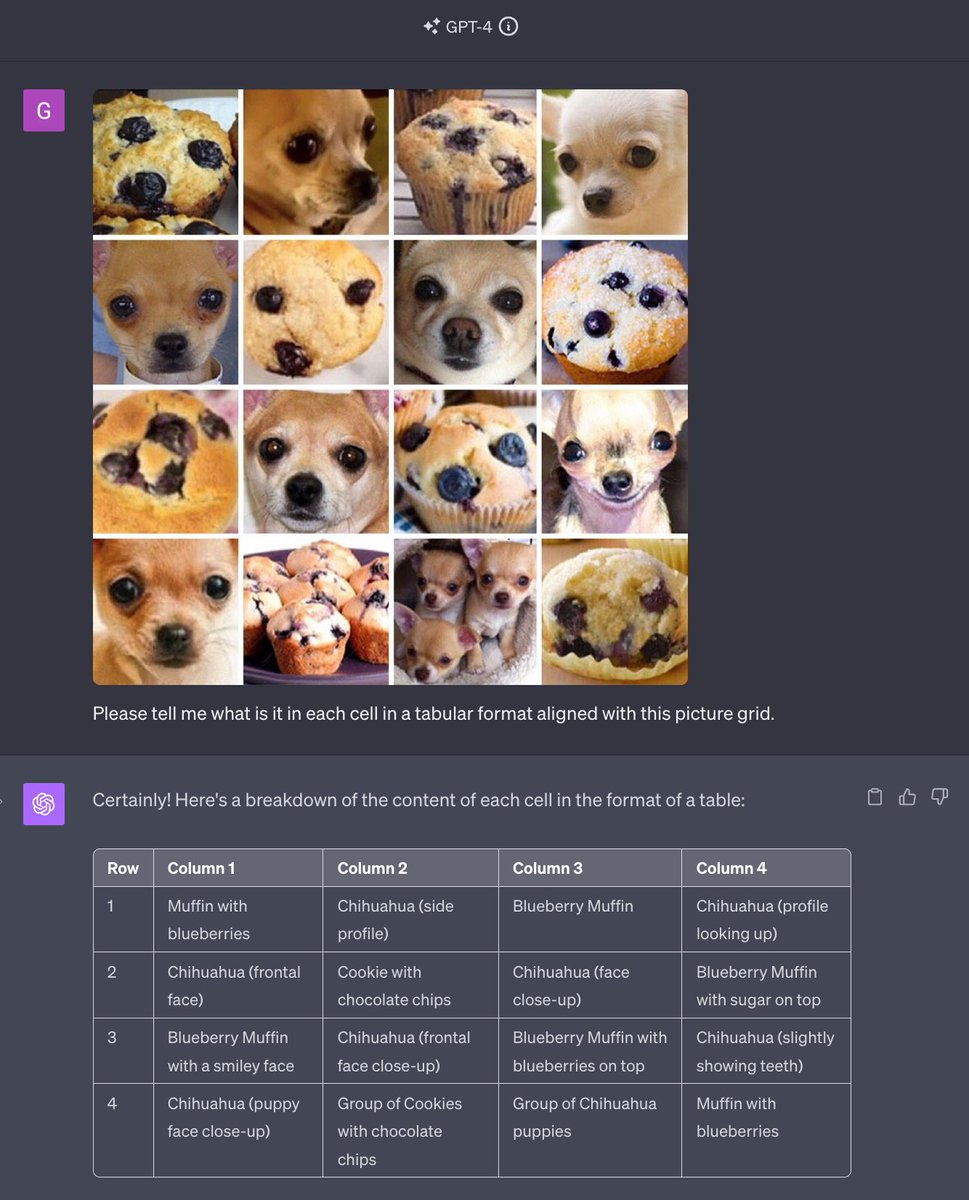

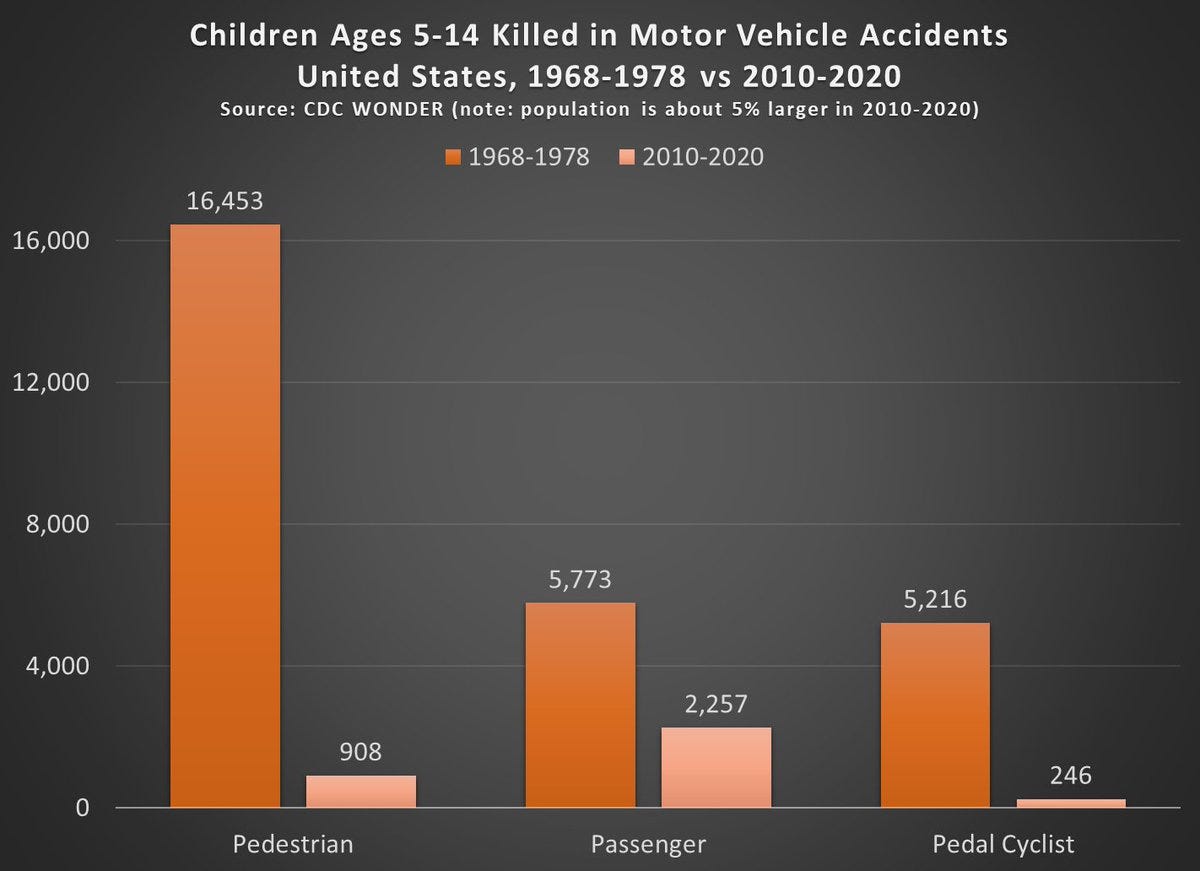

“The classic urbanist story is that cars have become safer for passengers by becoming more deadly (bigger/heavier) for pedestrians. This data cuts strongly against that story. I presume the urbanist response is mostly that sprawl/car culture have decreased pedestrian exposure?” (@atrembath)

Aesthetics/culture

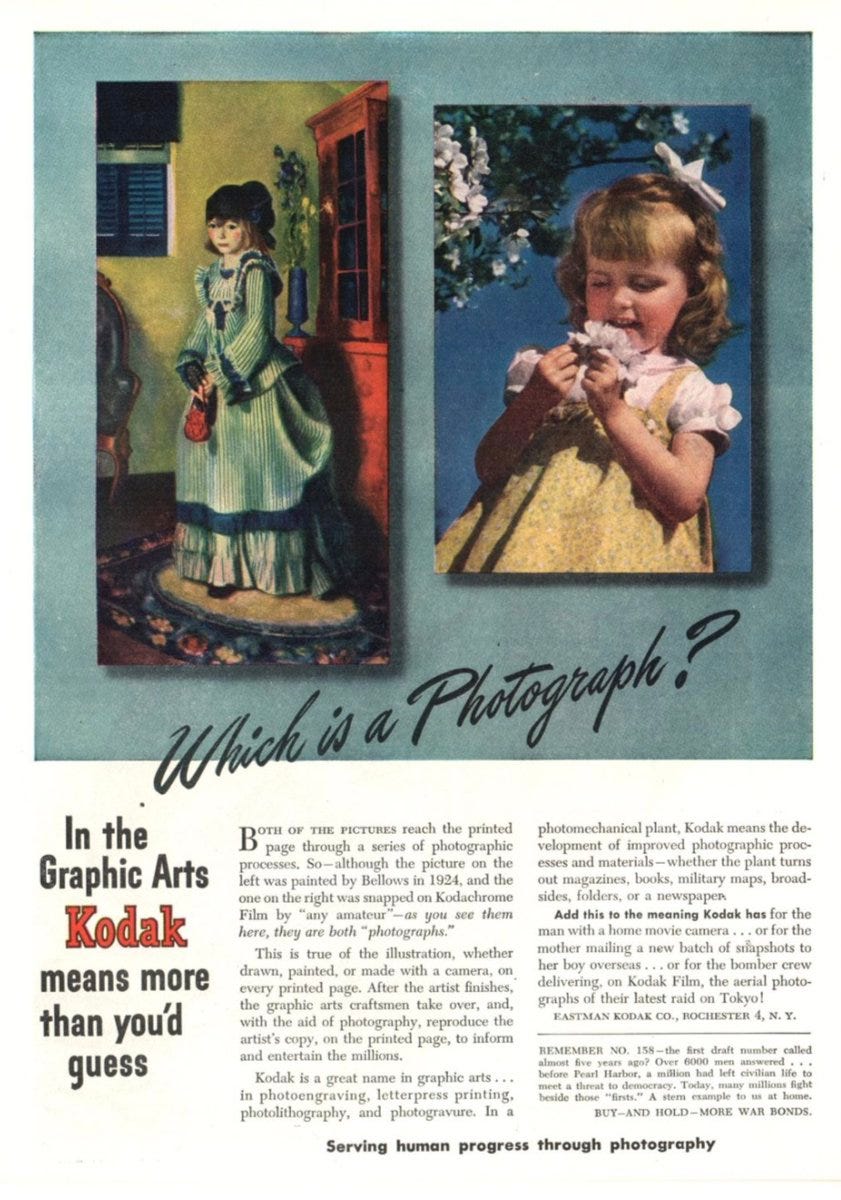

“Serving human progress through photography.” TIME Magazine, Aug. 20, 1945 (h/t Laura London) (Threads, Twitter):

Fun

“On one hand, AI is going to be incredibly disruptive for visual artists, but on the other hand: Jean-Jacquet Rousseau” (@kendrictonn)

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/links-digest-2023-11-07

>but wasn’t DNA present from the origins of life?

He's probably referring to the "RNA world" hypothesis, where RNA arose before DNA. DNA is more stable and a better storage molecule for genetic information. This is relatively well-supported by molecular evidence although we can't go back billions of years and check directly.