What I've been reading, October 2023

Also: Luminary.fm podcast with Erik Cederwall and Sachin Gandhi

Following the successful launch of The Roots of Progress Fellowship, we are now kicking off a fall fundraising drive to support and expand the program in 2024 and beyond. View our full fundraising pitch and see how to donate here.

In this update:

Full text below, or click any link above to jump to an individual post on the blog. If this digest gets cut off in your email, click the headline above to read it on the web.

What I've been reading, October 2023: The stirrup in Europe, 19th-century art deco, and more

A ~monthly feature. Last month was busy for me with a lot of travel and a lot of focus on The Roots of Progress as a nonprofit organization, so I haven’t had as much time as I prefer for research and writing. Recent blog posts and news stories are generally omitted; you can find them in my links digests. All emphasis in bold in the quotes below was added by me.

Histories of technology

Finished Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress (1990), which I mentioned last time. The first part of the book is a summary of Western technological development from ancient times through the Industrial Revolution. The second part explores the causes of that development by looking at three contrasts: classical antiquity vs. the medieval period, Europe vs. China, and Britain vs. the rest of Europe.

The book is worth a full review, for now I’ll just leave you with one insightful quote, in the chapter where Mokyr considers the analogy between technological development and biological evolution:

The study of genetics is the study of the causes of genetic variation in the population. Yet genetics has contributed little to our understanding of speciation and nothing to our understanding of extinction (Lewontin, 1974, p. 12). Economic analysis, which postulates that techniques will be chosen by profit-maximizing firms employing engineers in whose minds the genotypes of various techniques are lodged, plays a role analogous to genetics. It explains how demand and supply produce a variety of techniques, and points to the constraining influences of environment and competition as a limit to the degree of variety. Just as genetics by itself does not explain speciation, economic analysis has difficulty explaining macroinventions. Like evolution, technological progress was neither destiny nor fluke. Yet the power of Darwinian logic—natural selection imposed on blind variation—is that we need not choose between the two.

I’m now about halfway through Lynn White, Medieval Technology and Social Change (1962)—another classic. White covers three major developments: the stirrup, the use of horses as draft animals, and the development of mechanical power. The focus is on the social change that these new technologies precipitated.

Famously, White argues that the stirrup created feudalism. The stirrup allowed the rider to brace himself more firmly on his horse, which enabled a new type of mounted combat using lances that was superior to troops on foot or archers on horseback. Horses were expensive (as were armor and lances), and it required land to feed them, so land was taken away from the church and given to vassals who would, in exchange, give service to the sovereign as mounted warriors. In time, an entire culture grew up around this: these vassals became knights, with their own code of virtues (chivalry), their own training and games (tournaments), etc.

Other historians had previously traced back the development of feudalism to this new type of combat, and to Charles Martel who instigated it, but had looked for political or other social causes for the military change (one hypothesis, for instance, was that the famous battle against the Saracens at Poitiers motivated Charles to seek superior military tactics, even though he won). White’s contribution is to argue that the trigger for all of this was ultimately not social, but technological.

My only complaint so far is that White missed the chance to name this book The Stirrup in Europe.

Also on my to-read list: Friedrich Klemm, A History of Western Technology (1959), which was cited a lot by Mokyr.

Agriculture

In snatches of time, I am still researching agriculture for my book. Recently I’ve been reviewing historical sources on 19th-century “manures,” which today we would probably call fertilizers. It was an era when farmers were eager to find new fertilizers to improve agricultural yields, in order to meet growing demand for food from a rapidly growing population. However, agricultural chemistry was still developing, and synthetic fertilizers were decades away. Instead, farmers and scientists alike experimented with all sorts of natural fertilizers.

Both Humphry Davy, Elements of Agricultural Chemistry (1813); and Jean-Baptiste Boussingault, Rural Economy, in its Relations with Chemistry, Physics, and Meteorology (1860), have chapters on manures in which they catalog long lists of substances then in use. Dung and urine, both from animals and from humans, is of course a major feature, but it might surprise you how highly these substances were prized in the 19th century. For instance, Boussingault says:

Any expense incurred in improving this vital department of the farm, is soon repaid beyond all proportion to the outlay. The industry and the intelligence possessed by the farmer, may indeed almost be judged of at a glance by the care he bestows on his dunghill.

Later he praises Flanders for the “especial care” and “highly rational” method with which they collect human soil, which forms “the staple of an active traffic.” The Chinese, too, he notes approvingly, “collect human excrements with the greatest solicitude, vessels being placed for the purpose at regular distances along the most frequented ways.”

Fertilizers newly coming into widespread use the 19th century included oilseed cakes (formed from waste matter left over after seeds are pressed for their oil) and even bones, either broken into small pieces or ground into dust. The British demand for bones was so great, and their activities importing them from abroad so vigorous, that the German agricultural chemist Justus Liebig famously complained:

Great Britain deprives all countries of the conditions of their fertility. It has raked up the battle-fields of Leipzig, Waterloo, and the Crimea; it has consumed the bones of many generations accumulated in the catacombs of Sicily; and now annually destroys the food for a future generation of three millions and a half of people. Like a vampire it hangs on the breast of Europe, and even the world, sucking its lifeblood without any real necessity or permanent gain for itself.

(Thanks to Anton Howes for that quote)

Davy and Boussingault also suggest using as fertilizer: ashes and soot; woolen rags; shells, seaweed, mud, and slime from the sea-shore and river bottoms; refuse from the manufacture of sugar, starch, tallow, and glue; and scraps and trimmings of all types of animal remains, including hides, hair, tendons, feathers, even coagulated blood. Clearly, farmers were desperate for any source of fertility they could get.

Starting in the 1840s, another fertilizer came into use: seabird guano, mostly found on islands off the coast of Peru. James F. W. Johnston, “On Guano” (1841), describes the phenomenon:

It forms irregular and limited deposits, which at times attain a depth of 50 or 60 feet (Humboldt), and are excavated like mines of iron ochre. … In the isles of Islay and Jesus 20 to 25 tons of this recent guano are occasionally collected in a single season.

This paper was published at the beginning of the guano trade, but already the end was in sight: “it does not appear, as some have been led to believe, that the supply of this substance on the cost of Peru is by any means inexhaustible.” Forty years later much of the resource was consumed, and the trade was rapidly falling off. Imported guano was ultimately replaced by synthetic fertilizer based on the Haber-Bosch process.

Design

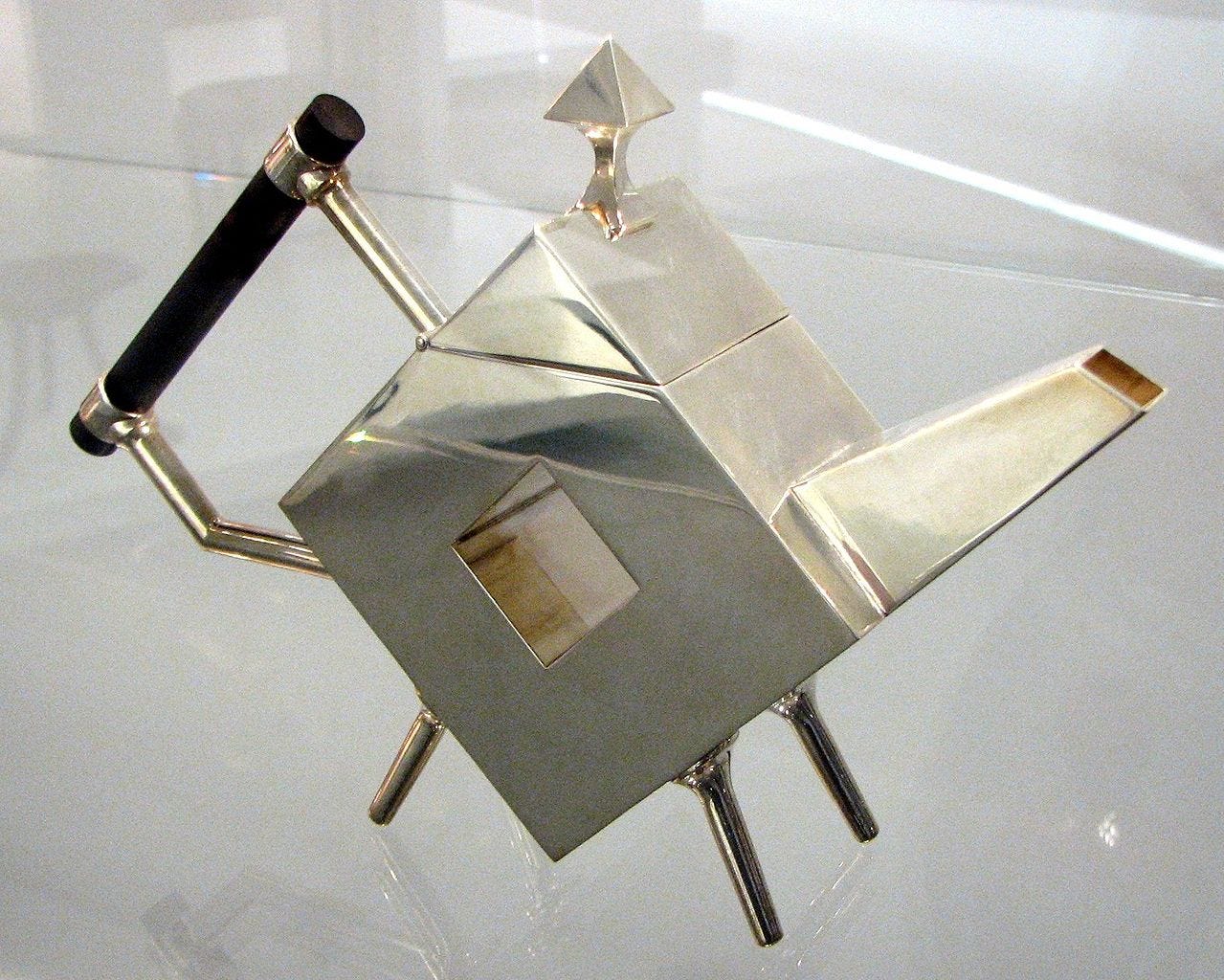

I attended an interesting talk on Christopher Dresser, who has been called the first industrial designer. In the 1870s or so, he was designing tea kettles, letter holders, and other objects that look as if they’re straight out of the Art Deco 1930s:

This led to me perusing his book Principles of Decorative Design (1870), or at least the introduction. Dresser has a strong moralistic sense of the importance of design:

Men of the lowest degree of intelligence can dig clay, iron, or copper, or quarry stone; but these materials, if bearing the impress of mind, are ennobled and rendered valuable, and the more strongly the material is marked with this ennobling impress the more valuable it becomes.

I must qualify my last statement, for there are possible cases in which the impress of mind may degrade rather than exalt, and take from rather than enhance, the value of a material. To ennoble, the mind must be noble; if debased, it can only debase. Let the mind be refined and pure, and the more fully it impresses itself upon a material, the more lovely does the material become, for thereby it has received the impress of refinement and purity; but if the mind be debased and impure, the more does the matter to which its nature is transmitted become degraded. Let me have a simple mass of clay as a candle-holder rather than the earthen candlestick which only presents such a form as is the natural outgoing of a degraded mind.

Later, in an oft-quoted paragraph, he says:

There can be morality or immorality in art, the utterance of truth or of falsehood; and by his art the ornamentist may exalt or debase a nation.

Most of the book, though, is about the “true principles of ornamentation”:

We shall carefully consider certain general principles, which are either common to all fine arts or govern the production or arrangement of ornamental forms: then we shall notice the laws which regulate the combination of colours, and the application of colours to objects; after which we shall review our various art-manufactures, and consider art as associated with the manufacturing industries. We shall thus be led to consider furniture, earthenware, table and window glass, wall decorations, carpets, floor cloths, window-hangings, dress fabrics, works in silver and gold, hardware, and whatever is a combination of art and manufacture. I shall address myself, then, to the carpenter, the cabinet-maker, potter, glass-blower, paper-stainer, weaver and dyer, silversmith, blacksmith, gas-finisher, designer, and all who are in any way engaged in the production of art-objects.

Also on my to-read list now:

Louis Sullivan, A System of Architectural Ornament (1924)

Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture (1923)

Tom Wolfe, From Bauhaus to Our House (1981)

Law

Scott Alexander reviews Njal’s Saga. (The review was an anonymous entry into Scott’s own book review contest; it received the most reader votes, but Scott graciously disqualified himself from winning his own contest.) The book is about justice in medieval Iceland, which had no police or regulators, but which did have a court. Justice in this society was often meted out via family feuds, that is, families and other coalitions often attacked and killed each other for revenge. But grievances could also be brought to court. If the court decided that, to compensate for a revenge killing, the killer should pay a fine (the weregild), maybe that could end the matter and stop the cycle of killing. In the saga, peaceful resolution often depends on the wise elder Njal; when Njal himself is killed and is no longer around to give advice, a lot of the peace unravels.

Related: by coincidence, I also came across Arnold Kling, “State, Clan, and Liberty” (2013); a review of Mark Weiner’s The Rule of the Clan, which is also about medieval Iceland and its legal system. Some excerpts:

[Weiner] finds a pattern of order that he calls the rule of the clan, which does not require a strong central state. However, he shows that rule of the clan relies on a set of rules and social norms which are inconsistent with libertarian values of peace, open commerce, and individual autonomy. …

Weiner grounds his analysis in the tradition of legal historian Henry Maine, who distinguished between the Society of Status and the Society of Contract. In the former, law is oriented toward the extended family as a group. In the latter, law is oriented toward the individual.

Kling summarizes Weiner’s thesis, “from a libertarian perspective”, as:

A decentralized order is possible. Indeed, it is natural for human societies to achieve such an order, rather than degenerate into the Hobbesian war of all against all.

The natural decentralized order is, however, highly illiberal. It requires a set of social norms that bind the individual to the clan. Under the rule of the clan, peace is broken by feuds, commerce is crippled by the inability to put trade with strangers on a contractual basis, and individual autonomy is sacrificed for group solidarity.

In the absence of a strong central state, the rule of the clan is the inevitable result. In order to graduate from the society of Status to the society of Contract, you must have a strong central state.

(Kling says he finds point 3 plausible but not fully persuasive.)

I recommend reading both pieces.

Biology

Sergey Markov, “A Future History of Biomedical Progress” (2022). This made the rounds a month or two ago. It starts with a long discussion of part of the frontier of biotech tools and techniques, which you can skim or skip if you want to get to the core idea. The core idea is: we’re going to need AI to design and engineer advanced biotech, because biology is so complicated that it is intractable to create human-legible models of the entire system. Rather than learn ourselves, directly, which genes do what and what the functions of each protein are and what pathways are involved in which processes, we’ll put all of the inputs and outputs into a big ML model and have it learn.

The secondary idea in the essay is that in order to do this, we’re going to need platforms to do very high-fidelity experiments, the results of which are highly transferrable to the systems that we actually care about, such as the human body. Mouse models might not cut it; we might have to do things like grow entire human organs from stem cells in order to experiment on them and learn how they really work.

I’m far from an expert in this field, but I found these arguments plausible, particularly since the essays ties them into a broader principle, Rich Sutton’s well-known “bitter lesson” of ML: any system tailored by hand using specialized domain knowledge is eventually beaten by generic systems that learn everything from scratch, given sufficient scale in compute and training data.

I don’t think, however, that this means that humans will never understand biology. I am optimistic that AI can not only figure out the immense complexity of biological systems, but that it can also figure out how to explain it to humans.

Chris Wintersinger, “Making the proteins that living cells cannot make.” A brief description of a project being pursued by Speculative Technologies. For me, this was a glimpse into what a very ambitious biotech research project looks like. I liked this chart:

Other articles

Brian Potter, “How the Car Came to LA”:

How did we become a country where cars are the defining feature of urban life? What did that transformation look like?

Answering this question for the entire country would be an enormous undertaking. But the book Los Angeles and the Automobile, by Scott Bottles, tries to answer it for LA, one of the most car-centric cities in the US. Over a period of less than 30 years, Los Angeles was transformed from a city with streetcar and train-based transportation to one where the car reigned supreme.

Benjamin Franklin letter on lead poisoning (1786). I mentioned last time a history of lead, which pointed out that lead has been known to be toxic since antiquity. This was one of the sources it cited, a letter from Benjamin Franklin on what he knew of “the bad Effects of Lead taken inwardly”:

You will see by it, that the Opinion of this mischievous Effect from Lead, is at least above Sixty Years old; and you will observe with Concern how long a useful Truth may be known, and exist, before it is generally receiv’d and practis’d on.

Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History” (1940). I was disappointed with this, but it does contain this remarkable quote (I’ll take the translation from a different source):

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

(After that vivid description, incidentally, I found the actual painting quite underwhelming)

Milton Friedman, “How to Cure Health Care” (2001):

Since the end of World War II, the provision of medical care in the United States and other advanced countries has displayed three major features: first, rapid advances in the science of medicine; second, large increases in spending, both in terms of inflation-adjusted dollars per person and the fraction of national income spent on medical care; and third, rising dissatisfaction with the delivery of medical care, on the part of both consumers of medical care and physicians and other suppliers of medical care.

Thanks to Roots of Progress fellow Tina Marsh Dalton for the link.

Scott Aaronson, “The Kolmogorov option” (2017). It’s important to speak the truth, even when the truth is unpopular—but it’s not worth martyring yourself for no purpose, if the Powers that Be punish truth-tellers. The Kolmogorov option (named after the Russian mathematician who exemplified it) is to choose your battles and bide your time until Power weakens and the truth-tellers can launch a coordinated attack. In response is Scott Alexander, “Kolmogorov Complicity And The Parable Of Lightning” (2017). The Kolmogorov option can work, but it’s difficult to pull off:

Kolmogorov’s curse is to watch slowly from his bubble as everyone less savvy than he is gets destroyed. The smartest and most honest will be destroyed first. Then any institution that reliably produces intellect or honesty. Then any philosophy that allows such institutions. … Then he and all the other savvy people can try to pick up the pieces as best they can, mourn their comrades, and watch the same thing happen all over again in the next generation.

The “parable of lightning” is an excellent illustration of how if a society insists on even a seemly tiny, insignificant lie, it will eventually spread to infect the entire society and to destroy all truth-seeking people and organizations. Recommended.

Scott Alexander, “Paradigms All The Way Down” (2019). (Scott is my favorite blogger, so I make no apologies for him appearing here three times.) Several epistemic paradigms are in broad strokes isomorphic; perhaps they are all saying the same thing about the relationship of theories and evidence?

Fiction

Ian Tregillis, The Alchemy Wars trilogy. I mentioned this last time when I had finished approximately the first book; now I’m well into the third. I hesitate to recommend any fiction too strongly before I’ve finished it, but so far I’m this is some of the best stuff I’ve read in a while.

Other items on my to-read list

Carroll Quigley, The Evolution of Civilizations: An Introduction to Historical Analysis (1961). Recommended by Ben Landau-Taylor, who summarizes part of it here.

Mark Aldrich, “Engineering Success and Disaster: American Railroad Bridges, 1840-1900” (1999). Thanks to Ben Schneider for recommending this in response to a post from me about 19th-century bridge collapses. Aldrich also wrote the book Safety First, which was the main source for my essay on factory safety.

G. K. Chesterton, What’s Wrong With the World (1910). Source of the well-known quote that “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult; and left untried.” True of many other ideals as well.

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/reading-2023-10

Podcast interview: Luminary.fm with Erik Cederwall and Sachin Gandhi

I was a guest on the podcast Luminary.fm:

Our conversation with Jason centers around progress and the history of technology. We cover the relationship between human civilization and technology, assorted inventions, and lessons to consider in the development and implementation of future technologies. We also talk about why progress matters, how things went wrong in the 20th century, and Jason’s idea of a new philosophy of progress. Jason has encyclopedic knowledge of diverse topics which made this an especially rich conversation.

Listen on the show page, Apple or Spotify.

Links digest: Dyson sphere thermodynamics and a cure for cavities

I’ve been traveling for a while, so this is a long one, covering the last ~month. I tried to cut it down, but there have been so many amazing announcements, opportunities, etc.! Feel free to skim and jump around:

From the Roots of Progress fellows

Connor O’Brien and Adam Ozimek have a new proposal, the Chipmaker’s Visa, “to ensure the fabs we’re spinning up have the specialized talent they need immediately” (via @cojobrien)

On the Progress Forum

“The Knowledge Machine delves deep into the interplay between systems thinking and human nature, starting with a thought-provoking idea: most people lack the inherent drive to pursue knowledge.” Science Despite the Fragility of Scientists

“There exists a fundamental mismatch in scale that means no one really represents the interests of the overall Bay Area, nor has the power to govern it coherently. This is causing a fundamental breakdown.” It’s Time for Greater San Francisco

Events

DC, Oct 16: Anticipating the Future with Virginia Postrel and Jim Pethokoukis

San Francisco, Dec 1–3: I’ll be at the Foresight Institute’s Vision Weekend USA, speaking on an “Existential Hope” panel

Prizes

A $10,000 challenge for writings of a positive future made with biology. Deadline extended to Oct 15 (via @NikoMcCarty, @HomeworldBio)

For science journalists: The Good Science Project is joining with Johns Hopkins to sponsor a set of awards for reporting on science policy issues (via @stuartbuck1)

The Progress Prize. “The best blog gets £5,000 plus other goodies” (via @Tom_Westgarth15)

“Will give £100 to anyone who can come up with a catchy alternative term for ‘the British Industrial Revolution’ that I can use without cringing” (@antonhowes)

Opportunities

“Are you a people-wrangling project manager who wants to bring more awesome science and technology into the world? Then check out our new short term job posting here” (via @Spec__Tech)

Ideas Matter: An 8-week writing fellowship for biology (via @NikoMcCarty)

“We’re looking for someone to help us at @fiftyyears with a research project on the history of technological progress, its future, and the potential contribution to a thriving future” (via @sethbannon)

“I’m working on charting technological progress in different mediums (electrons, atoms, bits, …) over time. Know anyone who might want to work with me on a short term (1-2 weeks) data gathering and analytics project?” (@fuelfive)

Microsoft is hiring a “principal program manager of of nuclear technologies” to implement a small and micro reactor strategy (via @Atomicrod)

“I’m helping to find UK based young people who are interested in being involved in applied metascience for an event” (@AnEmergentI)

Announcements

NSF partners with the Institute for Progress to test new mechanisms for funding research and innovation, reports (@AlecStapp)

Helion is building a 500 MW fusion power plant at Nucor steelmaking facility (via @dekirtley)

Laura Deming launches a new longevity fund (via @LauraDeming)

ARIA announces their first set of Programme Directors (via @ilangur). One of them is @davidad, who will be working on “accelerating mathematical modelling of real-world phenomena using AI”

Neuralink is recruiting for their first-in-human clinical trial, for those with quadriplegia due to cervical spinal cord injury or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (via @neuralink)

Karkió and Weissman win the Nobel for mRNA

In case you missed it, “The 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman for their discoveries concerning nucleoside base modifications that enabled the development of effective mRNA vaccines against COVID-19” (via @NobelPrize)

I highly recommend Joseph Walker’s interview with Karikó on the Jolly Swagman podcast. Before I heard it, I knew Karikó was an extraordinary scientist. After I heard it, I knew she also has an extraordinary character and is a deeply admirable human being

However, years ago, Karikó was denied grants and tenure. Does this prove there is something wrong with the grant/tenure systems? I don’t think it does, exactly. I explain why on Threads and Twitter

RIP

“Nick Crafts’ death has robbed Economic History of a clear thinker, an outstanding researcher, an excellent writer, a committed teacher and a wonderful colleague and mentor” (@timleunig)

News

The world now has a second vaccine against malaria (via @_HannahRitchie). @salonium comments, “When I was an undergrad, I was told that it wasn’t possible we’d have a malaria vaccine. Now there are two.”

San Francisco legalizes housing: a new law means that “most housing developments (including market-rate) in SF get streamlined, objective approvals … No CEQA, discretionary review, appeal” (via @anniefryman and @Scott_Wiener)

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission has succeeded in collecting a sample from an asteroid: “the extraterrestrial regolith sample has safely landed in Utah” (@AJamesMcCarthy). “Humankind has successfully returned a primordial piece of the Solar System that’s billions of years old” (@ThePlanetaryGuy). Also the PI on the project had an excellent out-of-office message

In other space news, “The Webb telescope has detected carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere of exoplanet K2-18 b, a potentially habitable world over 8 times bigger than Earth. Webb’s data suggests the planet might be covered in ocean, with a hydrogen-rich atmosphere” (@NASAWebb)

The CFTC rejected Kalshi’s proposal to list election markets; Kalshi responds: “the decision is arbitrary and capricious” (@mansourtarek_)

AI

Amazon will invest up to $4 billion in Anthropic (via @AnthropicAI). Also, Imbue (previously known as Generally Intelligent) has raised $200M “to build AI systems that can reason and code” (via @kanjun)

Anthropic makes progress on interpretability: “We demonstrate a method for decomposing groups of neurons into interpretable features” (@AnthropicAI, paper here)

ChatGPT can now see, hear, speak, and browse the internet. It is also integrated into DALL·E 3. It can even find Waldo

“GELLO is an intuitive and low cost teleoperation device for robot arms that costs less than $300” (@philippswu, cool videos, paper on Arxiv)

A new paper assesses “if AI will accelerate economic growth by as much as growth accelerated during the industrial revolution, digging into growth theory, bottlenecks, feasibility of regulation, AI reliability/alignment, etc. Takeaway: acceleration looks plausible” (@tamaybes)

“With many 🧩 dropping recently, a more complete picture is emerging of LLMs not as a chatbot, but the kernel process of a new Operating System,” says @karpathy

Very good thoughts on AI x-risk from Michael Nielsen. I agree that right now it is hard to make a very good case either for or against x-risk, and that consequently the quality of discussion has been poor, with most people falling back on tribes/vibes

Queries

“Does anyone have any good sources on our tax structures and how they are meant to support local vs. federal governments?” Also, “Will income tax be the best way to tax in the future?”

Books

Newly available:

The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised, by @JimPethokoukis

The Capitalist Manifesto: Why the Global Free Market Will Save the World, by @johanknorberg

Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Essential Wit & Wisdom of Charles T. Munger, with a new foreword by John Collison, from @stripepress

Founder vs Investor: The Honest Truth About Venture Capital from Startup to IPO, by Jerry Neumann and Elizabeth Zalman

Podcasts

Lex Fridman interviews Mark Zuckerberg in the metaverse as photorealistic avatars

Is Decentralized Science the Future of Discovery? with Seemay Chou, Vincent Weisser, and Allison Duettmann (via @AustinNxPodcast)

Papers

Dyson Sphere thermodynamics: Would Matrioshka brains actually make sense? @Astro_Wright investigates

Killing Kings: Patterns of Regicide in Europe, AD 600–1800. “Calculated as a homicide rate per ruler-year the risk of being killed amounts to [1% per year], making ‘monarch’ the most dangerous occupation known in criminological research” (@StefanFSchubert)

“A lot of interesting things in a study that mapped 1,313 ancient human remains for pathogens. Here is the rate of zoonotic diseases over time, showing that the spread of animal husbandry out of the mid-east coincided with the spread of zoonotic diseases” (and more in this thread from @lefineder)

Links

“The world as a whole underrates ‘elasticity of supply’ as an essential concept” (@tylercowen)

“Monday marks the 250th anniversary of birth of the most important scientist you’ve never heard of” (via @vpostrel)

A call for a “media temperance movement”, for a public who is drunk on media. Targeting: social media use, especially among young people; solitary media consumption; the decline in reading the printed page; and political infotainment. I support both alcohol and media usage, but both must be consumed in moderation—and if you can’t handle yourself, maybe you should be a teetotaler.

The Four Instruments Of Expansion: “the four different ways that civilizations have organized their economies throughout known history” (@benlandautaylor)

“Cavities were cured in 1985, and no one knows it yet. It is possible to genetically engineer Streptococcus mutans, the dominant human mouth bacteria, to produce ethanol instead of cavity-causing lactic acid. Further modifications cause it to outcompete native mouth bacteria, without spreading outside of the mouth. All research suggests that a one-time brushing of this GMO strain onto the teeth will dramatically reduce, or entirely eliminate, dental caries” (Lantern Bioworks). This is a pet idea of mine, but see the replies here for some potential problems

Social media

This still blows my mind: in the late 1800s, ~25% of bridges built just collapsed. @danwwang adds a claim about Shenzhen: “Of the new skyscrapers and offices, an eighth of those built in the early 1980s either simply fell down or suffered major structural problems”

“A 2000 ton spaceship that’s 900 tons antihydrogen, 900 tons hydrogen and 200 tons engines, structure and payload” could “accelerate to 0.92C with 2.55x time dilation, enough to reach the closest star in 21.4 months subjective time” (@ToughSf)

“Eternal problem of progress: if you fix a problem (or diminish it enough), your descendants will forget that the conditions in which they live are privileged ones, and will (in their ignorance and arrogance) destroy the foundations of that progress” (@SarahTheHaider). This is why the history of progress needs to be part of the curriculum for every student—so we never forget.

“Ideas ‘cast shadows’ into the future. It would be interesting to examine ideas that flourished for a time, then completely died out” (@ID_AA_Carmack)

You’re spoiled for options if you graduate as an engineer today

“Another good progress studies project to fund would be a really thorough study of environmental review laws (NEPA, CEQA, etc.) We know shockingly little about their impacts considering how ubiquitous they are” (@_brianpotter)

Being queen in the 17th century: “Anne had seventeen pregnancies, of which five were live births. None of her children survived to adulthood” (via @StefanFSchubert)

“When Fat’h Ali became the Shah of Persia in 1797, he was given a set of the Encyclopædia Britannica’s 3rd edition, which he read completely; after this feat, he extended his royal title to include ‘Most Formidable Lord and Master of the Encyclopædia Britannica’.” (@curiouswavefn)

“How did fighter planes in the 1950s perform calculations before compact digital computers were available? With the Bendix Central Air Data Computer! This electromechanical analog computer used gears and cams to compute ‘air data’ for fighter planes such as the F-101” (thread by @kenshirriff)

Quotes

In the late 1800s, some enterprises basically just didn’t measure their business or track any real metrics, except for balancing their books annually. (!) Carnegie, Rockefeller, and others started measuring and found all sorts of inefficiencies to improve (The Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie)

As I became acquainted with the manufacture of iron I was greatly surprised to find that the cost of each of the various processes was unknown. Inquiries made of the leading manufacturers of Pittsburgh proved this. It was a lump business, and until stock was taken and the books balanced at the end of the year, the manufacturers were in total ignorance of results. I heard of men who thought their business at the end of the year would show a loss and had found a profit, and vice-versa. I felt as if we were moles burrowing in the dark, and this to me was intolerable.

How much the structure of business changed starting in the mid-19th century (John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge, The Company)

A firm structured like Sears, Roebuck in 1916, with thousands of employees, pensioners, and shareholders, did not exist in 1840—not even in the wild imaginings of some futuristic visionary. Back then, the bulk of economic activity was conducted through single-unit businesses, run and owned by independent traders, who would have been more familiar with the Merchant of Prato’s business methods than Henry Ford’s.

Electricity, literally a life-changing technology (Robert J. Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth)

One Wyoming ranch woman called the day when electricity arrived “my Day of Days because lights shone where lights had never been, the electric stove radiated heat, the washer turned, and an electric pump freed me from hauling water. The old hand pump is buried under six feet of snow, let it stay there! Good bye Old Toilet on the Hill! With the advent of the REA, that old book that was my life is closed and Book II is begun.”

Lower transport costs → more competition → better for consumers. Better engines, faster vehicles, cheaper energy all contribute to this (Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches)

A world of high transport costs is described by an economic model of monopolistic competition. One of the characteristics of such a model is that innovator and laggard can coexist side by side. In the region served by the innovator, lower production costs due to technological change meant a combination of higher profits for producers and lower prices for consumers. Nothing could force the laggards to follow suit, however, and the “survival of the cheapest” model so beloved by economists is short-circuited.

More examples of predicted resource shortages that never appeared (Virginia Postrel, The Future and Its Enemies)

Theodore Roosevelt warned of an impending “timber famine,” driven by the railroads’ insatiable demand for wood. The problem was solved not by the technocratic Forest Service but by the development of creosote to preserve cross-ties and by the railroads’ own natural limits. The story repeated itself with metals in the 1970s and 1980s, as various authorities foresaw shortages or outright exhaustion. Instead, consumers bought fewer refrigerators and automobiles, and more services and electronic gadgets. More efficient techniques and substitute materials reduced the amount of metal needed to make everything from cars to telephone wire. And the predicted shortages never appeared.

The loss of optimism about progress in the 20th century began with the World Wars, the Great Depression, and the rise of totalitarianism around the world (Gabriel A. Almond, Progress and Its Discontents)

The first powerful shock came in 1914 when the “civilized” nations of Europe—most of them boasting the advances of science and technology, education, and self-government—went to war with one another and quickly brought even non-European nations into the vortex of a global conflict. The world had scarcely recovered from the conflagration when other traumas followed: the Russian Revolution, fought, like the French Revolution, in the name of heroic ideals but demanding from its inception to the present unconscionable human sacrifices; fascism in its Italian and in its generic form; the Great Depression; Nazism, reaching its climax of bestiality in the scientifically organized wartime extermination camps of the Third Reich; the carnage of the Second World War; the war’s aftermath of spreading dictatorship and new armed conflicts; and the aborted hopes for democracy and economic advance in the emergent Third World countries.

Verdi’s opera Aïda was commissioned for the opening of the Suez Canal, but was completed late (Jean Strouse, Morgan)

The French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps organized efforts to dig a canal across the Suez isthmus in 1859. Ten years later, a few months after the completion of America’s transcontinental railroad, Empress Eugenie sailed from Port Said to Suez for the formal opening of the canal. Among the other dignitaries who attended were the Prince and Princess of Wales, Emperor Franz Joseph, and an envoy from the Pope. Verdi, commissioned to write an opera for the event, failed to complete it in time: Aïda premiered in Cairo in 1871.

The United States in 1945 (via @CPopeHC)

We own 70 per cent of the world’s automobiles and trucks, 50 per cent of the world’s telephones. We listen to 45 per cent of the world’s radios. We operate 35 per cent of the world’s railroads. We consume 59 per cent of the world’s petrolum, and 50 per cent of its rubber.

Aesthetics

The pre-WW2 covers of Fortune (via @simonsarris)

“Once, America found beauty in the blend of industry and nature—a train against the fiery dance at a steel mill. The smoke told tales of prosperity, each puff a testament to our relentless spirit. We embraced the aesthetic of ambition, and we were better for it” (@Itsjoeco)

Charts

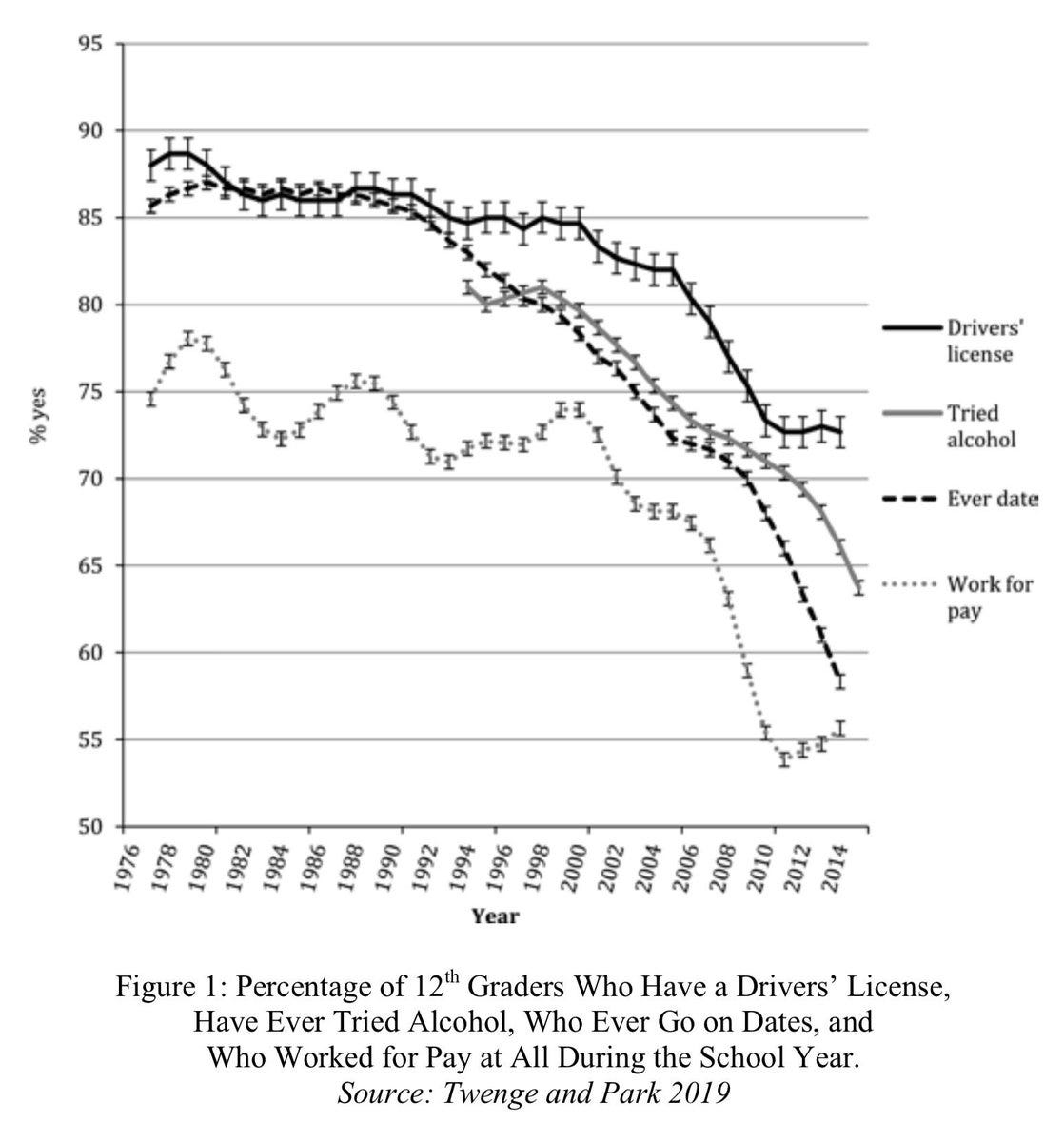

“What happened around the year 2000 that dramatically altered youth culture?” (@jayvanbavel)

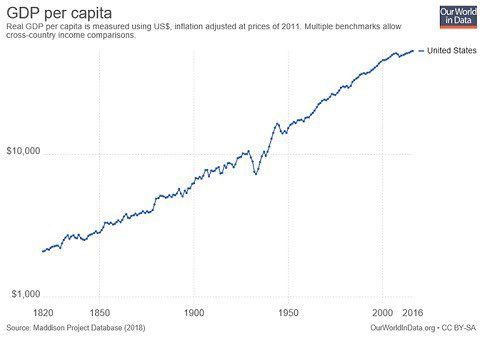

“Neither covid nor WW2 had any lasting effect on US GDP growth trends… our strong prior should be ‘unless this is literally more disruptive than WW2, things will revert to trend’” (@RichardMCNgo)

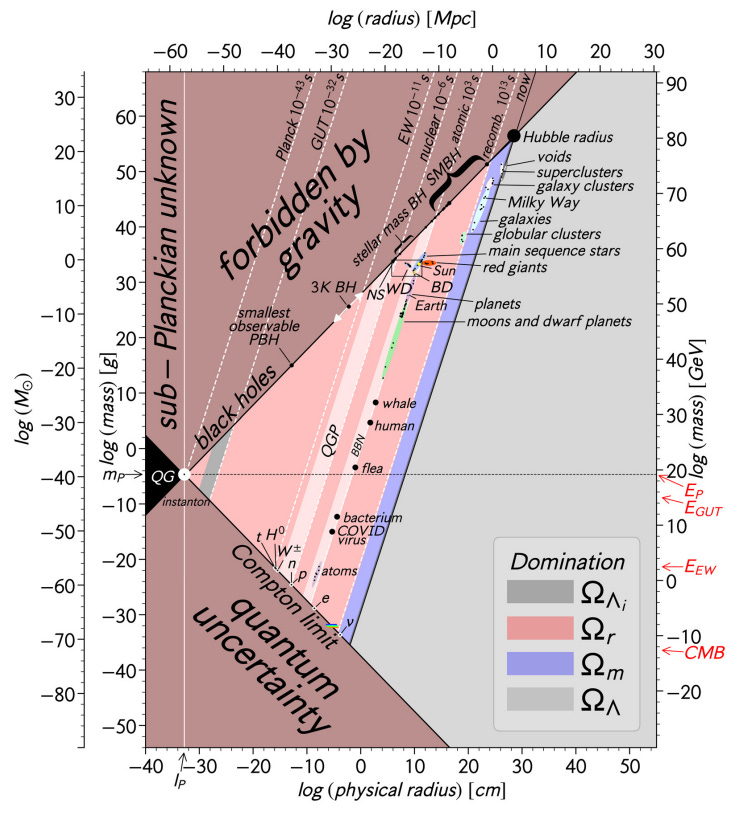

Everything, Everywhere, All On One Plot (via @AlexanderRKlotz)

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/links-digest-2023-10-12