Why no Roman Industrial Revolution?

Also, podcasts: Future of Life Institute, Breakthrough Science Summit panel

The Roots of Progress Blog-Building Intensive is an 8-week program for aspiring progress writers to start or grow a blog. Learn about progress studies, get into a regular writing habit, improve your writing, and build your audience:

In this update:

Full text below, or click any link above to jump to an individual post on the blog. If this digest gets cut off in your email, click the headline above to read it on the web.

Why no Roman Industrial Revolution?

Why didn’t the Roman Empire have an industrial revolution?

Bret Devereaux has an essay addressing that question, which multiple people have pointed me to at various times. In brief, Devereaux says that Britain industrialized through a very specific path, involving coal mines, steam engines, and textile production. The Roman Empire didn’t have those specific preconditions, and it’s not clear to him that any other path could have created an Industrial Revolution. So Rome didn’t have an IR because they didn’t have coal mines that they needed to pump water out of, they didn’t have a textile industry that was ready to make use of steam power, etc. (Although he says he can’t rule out alternative paths to industrialization, he doesn’t seem to give any weight to that possibility.)

I find this explanation intelligent, informed, and interesting—yet unsatisfying, in the same way and for the same reasons as I find Robert Allen’s explanation unsatisfying: I don’t believe that industrialization was so contingent on such very specific factors. When you consider the breadth of problems being solved and advances being made in so many different areas, the progress of that era looks less like a lucky break, and more like a general problem-solving ability getting applied to the challenge of human existence. (I tried to get Devereaux’s thoughts on this, but I guess he was too busy to give much of an answer.)

As a thought experiment: Suppose that British geology had been different, and it hadn’t had much coal. Would we still be living in a pre-industrial world, 300 years later? What about in 1000 years? This seems implausible to me.

Or, suppose there is an intelligent alien civilization that has been around for much longer than humans. Would you expect that they have definitely industrialized in some form? Or would it depend on the particular geology of their planet? Are fossil fuels the Great Filter? Again, implausible. I expect that given enough time, any sufficiently intelligent species would reach a high level of technology on the vast majority of habitable planets.

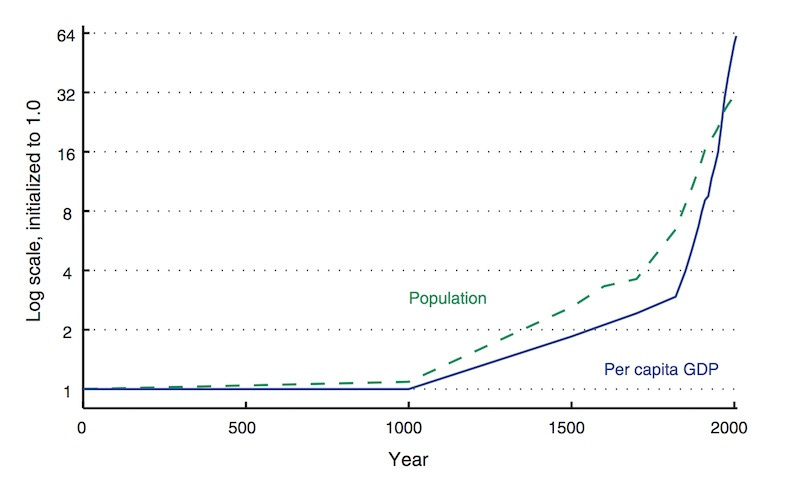

Devereaux asserts that there is a “deeply contingent nature of historical events … that data (like the charts of global GDP over centuries) can sometimes fail to capture.” I see this in reverse: the chart of global GDP over centuries is, to my mind, evidence that progress is not so contingent on random historical flukes, that there is a deeper underlying process driving it.

So why didn’t the Roman Empire have an industrial revolution?

Consider a related question: why didn’t the Roman Empire have an information revolution? Why didn’t they invent the computer? Presumably the answer is obvious: they were missing too many preconditions, such as electricity, not to mention math (if you think ENIAC’s decimal-based arithmetic was inefficient, imagine a computer trying to use Roman numerals). Even conceiving the computer, let alone inventing one, requires reaching a certain level of technological development first, and the Romans were nowhere near that.

I think the answer is roughly the same for why no Roman IR, it’s just a bit less obvious. Here are a few of the things the ancient Romans didn’t have:

The spinning wheel

The windmill

The horse collar

Cast iron

Latex rubber

The movable-type printing press

The mechanical clock

The compass

Arabic numerals

And a few other key inventions, such as the moldboard plow and the crank-and-connecting-rod, showed up only in the 3rd century or later, well past the peak of the Empire.

How are you going to industrialize when you don’t have cast iron to build machines out of, or basic mechanical linkages to use in them? How could a society increase labor productivity through automation when it hasn’t even approached the frontier of what is possible with simple wooden tools? Why even focus on improving labor productivity in manufacturing when productivity is still very low in agriculture, which is more fundamental? Why should it exploit coal when it has barely begun to exploit wind, water, and animal power? How are engineers to do experiments and calculations without any concept of the experimental method, and without anything close to the mathematical tools that are available today to any fifth-grader? And if anything was discovered or invented, how could the news spread widely when most information was hand-written on parchment?

All of the flywheels of progress—surplus wealth, materials and manufacturing ability, scientific knowledge and methods, large markets, communication networks, financial institutions, corporate and IP law—were turning very slowly. There is not a single, narrow path to industrialization, but you have to get there through some path, and ancient Rome was simply nowhere close. You can’t leapfrog over the spinning wheel to get to the spinning mule, and (this is one thing we learn from Allen’s analysis) it’s not clear that it even makes economic sense to do so.

In a sense, I’m saying the same thing as Devereaux: Rome couldn’t have had an IR because they didn’t have the preconditions. But rather than conceiving of those preconditions as very narrow and seeing the IR as highly contingent, I am taking a much broader view of the preconditions.

If Rome hadn’t collapsed, they might, within a matter of centuries, have advanced to the stage of industrialization. But they would have done it by skipping the Dark Ages and following an incremental course of technological and economic advancement that, if not identical to ours, would probably be not unrecognizable, and perhaps quite familiar.

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/why-no-roman-industrial-revolution

Podcasts: Future of Life Institute, Breakthrough Science Summit panel

Two new podcasts featuring me:

Future of Life Institute Podcast with Gus Docker

We covered the history of progress, the future of economic growth, and the relationship between progress and risks from AI:

00:00 Eras of human progress

06:47 Flywheels of progress

17:56 Main causes of progress

21:01 Progress and risk

32:49 Safety as part of progress

45:20 Slowing down specific technologies?

52:29 Four lenses on AI risk

58:48 Analogies causing disagreement

1:00:54 Solutionism about AI

1:10:43 Insurance, subsidies, and bug bounties for AI risk

1:13:24 How is AI different from other technologies?

1:15:54 Future scenarios of economic growth

Breakthrough Science Summit panel moderated by Ramez Naam

Former Prime Movers Lab Futurist Ramez Naam moderates a panel with The Roots of Progress Founder Jason Crawford, Idea Machines Host Ben Reinhardt, and Prime Movers Lab Venture Partner Amy Kruse to discuss the fundamental research that the US needs to invest in and how it will impact the economy.

The conversation is an excerpt from the Prime Movers Lab Breakthrough Science Summit hosted in Scottsdale, Arizona on October 27th, 2022.

As always, see all my talks and interviews here.

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/podcasts-future-of-life-institute-breakthrough-science-summit-panel

Links digest, 2023-07-28: The decadent opulence of modern capitalism

Opportunities

Applications are still open for The Roots of Progress Blog-Building Intensive, through Aug 11. Launch a blog, get into a regular writing habit, improve your writing, and begin building your audience

Longevity startup Loyal hiring a Marketing Director (via @celinehalioua)

Apply for the South Park Commons Founder Fellowship (via @adityaag)

Niko McCarty in SF this weekend, meet him and chat about synthetic bio

Announcements

Fervo Energy has demonstrated an advanced geothermal well that generated 3.5MW of electricity. Via @TimMLatimer: “Geothermal has long been held back by drilling costs. We just got a lot better at drilling”

Llama-v2 is open source, authorized for commercial use. Pre-trained models available with 7B, 13B and 70B parameters (via @ylecun)

ChatGPT now supports custom instructions. Because even @sama knows that it is too verbose and caveats too much

Links

Jake Seliger wants to make the FDA’s “invisible graveyard” a bit more visible: “I’m going to be buried in it, in a few weeks or months” (via @AlanMCole)

A game that tests your ability to predict how well GPT-4 will perform at various types of questions. I scored 85th percentile (B+) and was only slightly overconfident

Lessons learned about Focused Research Organizations (via @SGRodriques)

Dan Wang’s China notes. China sees LLMs as akin to social media: “technologies with little economic upside and significant political risk.” Social media apps “are not increasing TFP … they are freewheeling platforms for expression, with the potential to create political unrest.” But: “Americans are now integrating these tools into their lives. And they will start showing up in productivity statistics…. The longer that most Chinese are unable to work with them, the greater the risk that China will be left behind in some way”

An argument that ‘Oumuamua is probably a natural object (via @Astro_Wright)

Stanford President resigns over academic fraud (via @StanfordDaily)

Video

Converting scrap steel to rebar (via @Jess_Riedel)

Queries

How much nitrogen is required to grow a specific amount of produce, for various crops?

If Niko wrote an introductory book on genetic design, would you read it?

Quotes

Mokyr: Hope for progress in the 1700s was based on a metaphysical belief that nature is knowable

Andy Warhol (1975) and Harper’s Magazine (1957) on capitalist equality

Back when we couldn’t figure out what to do with computers, in 1977

Tweets and threads

Someone should write about science news the way Matt Levine writes about finance news. Related, someone should do a historical, progress-studies take on money and banking

Looking for big ideas? Scan mid–20th century government research papers

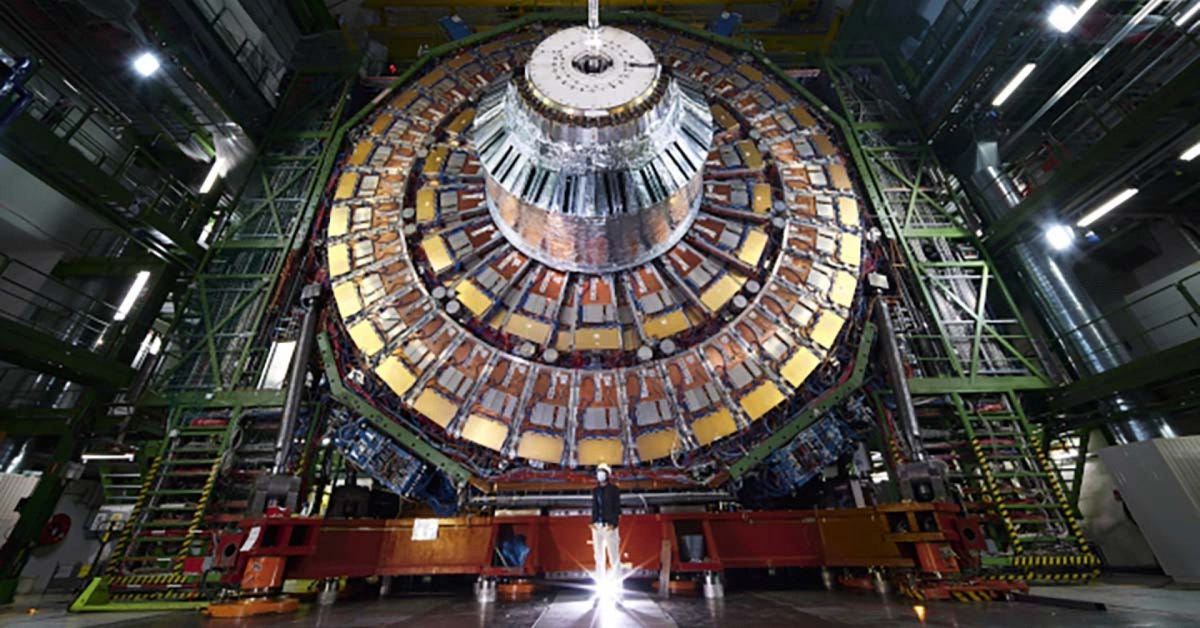

Anatoli Bugorski stuck his head into a particle accelerator, got hit with a proton beam, survived, and completed his PhD thesis. The 20th-century Phineas Gage

We’re not at the end-state of capitalism until you can buy fresh peaches all year

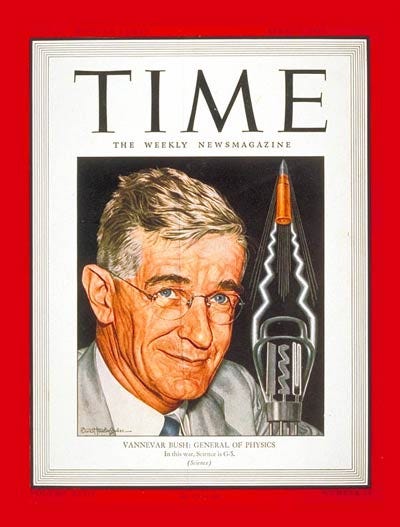

“Vannevar Bush: General of Physics”, TIME cover, April 1944 (via @calebwatney)

Closing thought

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/links-digest-2023-07-28

Interesting article, Jason.

In my estimation, several factors must have converged to spark an industrial revolution in the Roman Empire. Besides the importance of geography and geology (both of which would have determined their natural resources, weather patterns, and--to an extent--necessities for survival), innovative minds would have needed (i) free rein to pursue their ideas; (ii) financial support to develop them into machines; and (iii) an economic model that supports their adoption. Thus, in addition to its low-velocity flywheels of progress, the Roman Empire did not possess an environment for optimal flourishing of the intellect.

The Rome question is interesting. Another important reason industrialization did not happen in Rome is that, as you allude to with their lack of Arabic numerals, they didn’t think about mathematics and number as we do. Specifically, they hadn’t yet reached the point of thinking about physics and the natural world in mathematical terms. Makes certain kinds of engineering very difficult or impossible.