Developing a technology with safety in mind

Lessons from the Wright Brothers

In this update:

Full text below, or click any link above to jump to an individual post on the blog. If this digest gets cut off in your email, click the headline above to read it on the web.

Should I turn on Substack Chat for this newsletter?

Developing a technology with safety in mind: Lessons from the Wright Brothers

If a technology may introduce catastrophic risks, how do you develop it?

It occurred to me that the Wright Brothers’ approach to inventing the airplane might make a good case study.

The catastrophic risk for them, of course, was dying in a crash. This is exactly what happened to one of the Wrights’ predecessors, Otto Lilienthal, who attempted to fly using a kind of glider. He had many successful experiments, but one day he lost control, fell, and broke his neck.

Believe it or not, the news of Lilienthal’s death motivated the Wrights to take up the challenge of flying. Someone had to carry on the work! But they weren’t reckless. They wanted to avoid Lilienthal’s fate. So what was their approach?

First, they decided that the key problem to be solved was one of control. Before they even put a motor in a flying machine, they experimented for years with gliders, trying to solve the control problem. As Wilbur Wright wrote in a letter:

When once a machine is under proper control under all conditions, the motor problem will be quickly solved. A failure of a motor will then mean simply a slow descent and safe landing instead of a disastrous fall.

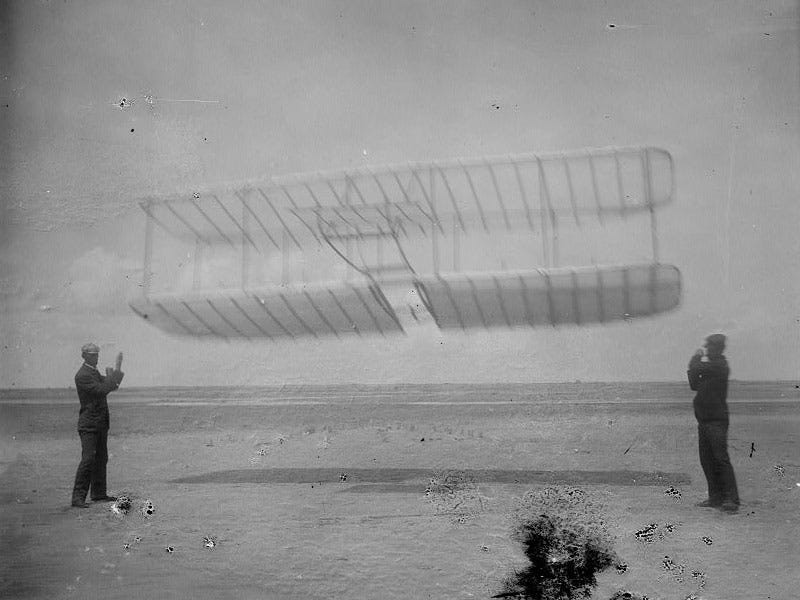

When actually experimenting with the machine, the Wrights would sometimes stand on the ground and fly the glider like a kite, which minimized the damage any crash could do:

When they did go up in the machine themselves, they flew relatively low. And they did all their experimentation on the beach at Kitty Hawk, so they had soft sand to land on.

All of this was a deliberate, conscious strategy. Here is how David McCullough describes it in his biography of the Wrights:

Well aware of how his father worried about his safety, Wilbur stressed that he did not intend to rise many feet from the ground, and on the chance that he were “upset,” there was nothing but soft sand on which to land. He was there to learn, not to take chances for thrills. “The man who wishes to keep at the problem long enough to really learn anything positively must not take dangerous risks. Carelessness and overconfidence are usually more dangerous than deliberately accepted risks.”

As time would show, caution and close attention to all advance preparations were to be the rule for the brothers. They would take risks when necessary, but they were no daredevils out to perform stunts and they never would be.

Solving the control problem required new inventions, including “wing warping” (later replaced by ailerons) and a tail designed for stability. They had to discover and learn to avoid pitfalls such as the tail spin. Once they had solved this, they added a motor and took flight.

Inventors who put power ahead of control failed. They launched planes hoping they could be steered once in the air. Most well-known is Samuel Langley, who had a head start on the Wrights and more funding. His final experiment crashed into the lake. (At least they were cautious enough to fly it over water rather than land.)

The Wrights invented the airplane using an empirical, trial-and-error approach. They had to learn from experience. They couldn’t have solved the control problem without actually building and testing a plane. There was no theory sufficient to guide them, and what theory did exist was often wrong. (In fact, the Wrights had to throw out the published tables of aerodynamic data, and make their own measurements, for which they designed and built their own wind tunnel.)

Nor could they create perfect safety. Orville Wright crashed a plane in one of their early demonstrations, severely injuring himself and killing the passenger, Army Lt. Thomas Selfridge. The excellent safety record of commercial aviation was only achieved incrementally, iteratively, over decades.

And of course the Wrights were lucky in one sense: the dangers of flight were obvious. Early X-ray technicians, in contrast, had no idea that they were dealing with a health hazard. They used bare hands to calibrate the machine, and many of them eventually had to have their hands amputated.

But even after the dangers of radiation were well known, not everyone was careful. Louis Slotin, physicist at Los Alamos, killed himself and sent others to the hospital in a reckless demonstration in which a screwdriver held in the hand was the only thing stopping a uranium core from going critical.

Exactly how careful to be—and what that means in practice—is a domain-specific judgment call that must be made by experts in the field, the technologists on the frontier of progress. Safety always has to be traded off against speed and cost. So I wouldn’t claim that this exact pattern can be directly transferred to any other field—such as AI.

But the Wrights can serve as one role model for how to integrate risk management into a development program. Be like them (and not like Slotin).

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/wright-brothers-and-safe-technology-development

Links and tweets: The illusion of moral decline, turnspit dogs, and more

Announcements & opportunities

Terraform Industries (carbon-neutral natural gas synthesis from solar) is hiring

A class on how politics works, so you can get involved productively

Read Something Wonderful, writing that has stood the test of time (including my pieces on iron and smallpox)

Turpentine Media, a new media network covering tech, business, & culture

News

Ted Kaczynski, the “Unabomber,” has died in prison at 81. See Kevin Kelly’s summary of and rebuttal to his philosophy

Links

Marc Andreessen on AI safety. Note what I highlighted and where I disagree

What Lant Pritchett is for: productivity, state capability, education, labor mobility

The Illusion of Moral Decline (via @a_m_mastroianni). One of many such illusions

The untold story of the precursors of the steam engine (by @antonhowes)

Holden Karnofsky suggests “a playbook for AI risk reduction”

Mark Lutter interview on his Caribbean charter city project (via @MarkLutter)

Trailer for Nuclear Now, which is now on streaming platforms (via @oklo)

Casey Handmer on why we don’t build underground. Building a road tunnel costs “$100,000 per meter, or equivalent to a stack of Hamiltons of the same length.” (!) Although I don’t know if Casey used Norway or Seattle figures

Also Casey: 1 gram of stratospheric SO2 offsets 1 ton of CO2 for 1 year (!)

“Existential Crunch” synthesizes research about social collapse (via @mattsclancy)

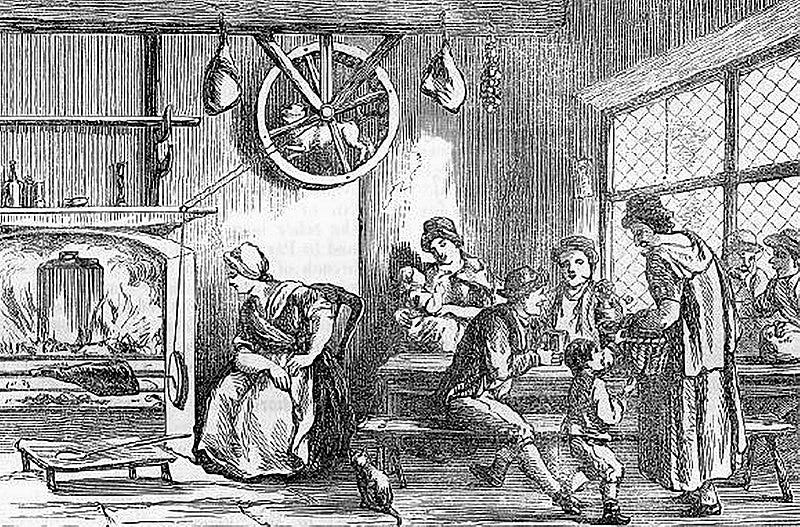

Turnspit dogs (via @RebeccaRideal via @antonhowes)

Requests for books/sources on…

Related, the modern history of chips/AI?

Other queries

What societies have successfully gone through degrowth? (If any…)

Anecdotes of scientists eschewing management or calling for more autonomy?

Term for the age you would have died at, if not for modern medicine?

Best treatment of why actions often produce the opposite of the intended effect?

How to square Cruise’s claim of 1 injury in first 1M driverless miles with SF’s claims? (Maybe three are actually Waymo, and none seem at-fault?)

Quotes

“The flying machine is one of God’s most gracious and precious gifts”

Admiral Rickover on academic reactors vs. practical reactors

The stock ticker was the 19th-century equivalent of social media

Straight, level roads were a new, non-obvious idea in the early 1800s

How the precautionary principle became a weapon against new technology

“Systems tend to malfunction conspicuously just after their greatest triumph”

Tweets & threads

Cruise AVs learn to honk at human drivers to avoid collisions

We have seen smoke blotting out the sky before, such as the “Dark Day” of 1780

Bret Devereaux on what life was like as a typical Roman peasant. Among other things, children died young and yes, the parents mourned

Author of “Mundanity of Excellence” responds to me on the value of talent

“Progress studies showed me that ideas matter & can have true real world impact”

A dam is sabotaged, and the main media concern is a nuclear plant at little risk

The apathy that manifests when technology becomes invisible. Also, “pragmatic optimism” and “solutionism”

What “consciousness-raising” feminism did and why it was necessary

How well-intentioned government policy turns into implementation nightmares

The O-1/EB-1 are underutilized by top talent; many get bad info about eligibility

SF changes the planning code to reduce burden on shop owners

I oscillate between “everything is screwed up” and “screwed-up is normal”. Also, the minimum competence of professionals is much lower than you would hope

Maps & charts

Original post: https://rootsofprogress.org/links-and-tweets-2023-06-14

Today, risk aversion appears to prevail over everything that we do. But without risk, there can be no progress. We must strike a balance between obsessive risk mitigation and the need for continued progress.

One outlier today is SpaceX. They are willing to employ an iterative approach, much like the Wright Brothers, building, testing, and failing to figure out where the flaws reside. SpaceX is comfortable with rockets blowing up, because the data these explosions provide ultimately will lead to safer designs.

Such a good piece!!!!! And so relevant today.