Previously: The Unlimited Horizon, part 1 and part 2

On a fine day late in May, 1883, hundreds of thousands of people gathered along the East River in New York City for a grand celebration.1 Perhaps a hundred thousand came from outside the city: by train, by boat, by wagon from the country. “The streets leading to the river were packed solid with people. … Every available rooftop and window was filled and along the river front there was scarcely a place left to stand.” Ships and boats gathered in the river in “a great, elongated flotilla”; the North Atlantic Squadron of five warships had been called in for the occasion. All the major hotels sold out by midday. President Chester A. Arthur was in attendance, along with then-governor Grover Cleveland, the mayor, and other officials. Many schools let out, federal courts were closed, most businesses were empty, and the floors of several exchanges were closed at noon.

They were not celebrating a war hero, a centennial, or a political inauguration. They were celebrating the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Vendors were hawking bridge buttons, commemorative medals, sheet music about the bridge, and facsimiles in metal, wax, or confection. Decorations were everywhere. “Virtually every single house and building downtown had a flag flying from its rooftop or hung from a window.” Buildings were covered in streamers and bunting; the dome of the courthouse was “gorgeous in its dress of flying colors.” The house of Washington Roebling, the Chief Engineer, “was covered with flags, shields, flowers, and the coat of arms of New York and Brooklyn”; the President would soon be received there. Framed portraits of Roebling hung in store windows. Some of the decorations were elaborate and creative: “A jeweler had made a miniature bridge with gold chain for the cables. A florist had made a bridge eight feet long, complete with bridge trains and boats passing below, all of flowers.” One decoration in City Hall Square depicted the growth of Brooklyn from a small village up to the completion of the bridge, and envisioned that a century in the future (that is, 1983) there would be a hundred bridges spanning the East River.

The ceremony began with a procession from Brooklyn: “The Twenty-third Regiment band in bright-red coats, followed by the Twenty-third Regiment in white helmets and blue coats, followed by a detachment of Fifth Artillery from Fort Hamilton and Marines from the Navy Yard, who in turn were followed by two hundred and some city officials, bridge trustees, and special guests, all in a body, led by the young mayor in a tall silk hat and followed by Mrs. Washington Roebling and her party in carriages.” The entire parade route was lined with crowds and people watching from rooftops. A brass band played and guns boomed from the Navy Yard as the President himself walked onto the bridge from the New York side. Then:

[Brooklyn Mayor] Seth Low made the official greeting for the City of Brooklyn, the Marines presented arms, a signal flag was dropped nearby and instantly there was a crash of a gun from the [warship] Tennessee. Then the whole fleet commenced firing. Steam whistles on every tug, steamboat, ferry, every factory along the river, began to scream. More cannon boomed. Bells rang, people were cheering wildly on every side. The band played “Hail to the Chief” maybe six or seven more times, and as the New York Sun reported, “the climax of fourteen years’ suspense seemed to have been reached, since the President of the United States of America had walked dry shod to Brooklyn from New York.”

Afterwards, more than a thousand guests visited Roebling’s house, including the President, the governor, and the mayors of New York and Brooklyn. Elsewhere, people partied all evening: “Every street on the Heights looked like a carnival. … No traffic was moving anywhere near the river. Uptown New York and the inland sections of Brooklyn were all but deserted. … The Times estimated there were 150,000 people just in the neighborhood of City Hall.” Around 8 p.m., “fourteen tons of fireworks—more than ten thousand pieces—were set off from the bridge”:

It lasted a solid hour. There was not a moment’s letup. One meteoric burst followed another. Rockets went off hundreds at a time and were seen from as far away as Montclair, New Jersey. … Meantime, innumerable gas balloons were being sent aloft. They were fifty feet in circumference and loaded with fireworks and as they swung into the sky, one by one, they scattered balls of colored fire over the river. …

From the middle of the bridge now came great thunderclap reports as zinc balls, fired from mortars, burst five hundred feet up, fairly illuminating the two cities, like sustained lightning.

And finally, at nine, as the display on the bridge ended with one incredible barrage—five hundred rockets fired all at once—every whistle and horn on the river joined in. The rockets “broke into millions of stars and a shower of golden rain which descended upon the bridge and the river.” Bells were rung, gongs were beaten, men and women yelled themselves hoarse, musicians blew themselves red in the face.

Hundreds of thousands of people were watching, and “nobody, in all his days, had ever seen anything like this.” At midnight, the bridge was opened to pedestrians, and thousands of people walked across it. “People poured across the bridge through the entire night and were still coming with the first light in the sky.”

Everyone, we might suppose, loves a party and a spectacle. But this was something more. The bridge had great spiritual and moral meaning. According to the speakers that day:

The bridge was a “wonder of Science,” an “astounding exhibition of the power of man to change the face of nature.” It was a monument to “enterprise, skill, faith, endurance.” It was also a monument to “public spirit,” “the moral qualities of the human soul,” and a great, everlasting symbol of “Peace.” The words used most often were “Science,” “Commerce,” and “Courage,” and some of the ideas expressed had the familiar ring of a Fourth of July oration. …

[E]very speaker that afternoon seemed to be saying that the opening of the bridge was a national event, that it was a triumph of human effort, and that it somehow marked a turning point. It was the beginning of something new, and although none of them appeared very sure what was going to be, they were confident it would be an improvement over the past and present. …

The bridge was a vindication, a heroic and monumental end result of modern industrialism, of labor and capital, of democracy, of new “methods, tools and laws of force”—of the nineteenth century.

The Bridge was called the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” It was likened to the pyramids, the Acropolis, and the hanging gardens of Babylon; Roebling was compared to da Vinci. Mayor Low said: “Not one shall see it and not feel prouder to be a man.”

The parade, the fireworks and the speeches were exemplary of the spirit of progress that imbued that era. The mainstream view was that progress was real, important, and good: that science, technology and industry had improved human life and society, and would continue to do so. This belief was strongest before World War 1, but lasted in some form through the 1960s.

This spirit enthusiastically celebrated inventive and industrial achievements. The Erie Canal was completed in 1825, connecting the Great Lakes with the Atlantic. The event, which came to be known as the Wedding of the Waters, was greeted with an “avalanche of lavish entertainments and ceremonies that consumed New York State as it greeted a dream coming true.”2 Celebrations began on October 26 and continued for well over a week as the governor and lieutenant governor rode a boat from Buffalo to New York City, stopping at more than twenty towns for ceremonies featuring guns, lights, parades, and fireworks. An allegorical painting was made showing Hercules resting from his labors in building the canal and Neptune, the god of the sea, astonished to see its locks opening before him. Artillery was lined up all along the route, each gun within hearing distance of the next, sending a signal down the line from Buffalo to Sandy Hook, NJ and back, a round trip which took more than two hours.

The welcoming committee in Albany included the Secretary of State and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. The festivities that evening included “an elaborate theater performance of odes, a full drama, and a canal scene with locks, including horses and boats actually passing across the stage.” As they approached Manhattan, they were met by a brand new steamboat “covered with the most elaborate kinds of decorations, flaming torches, and sculptured figures celebrating George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, agriculture, commerce, and even the whole globe of the earth.” (Lafayette himself had visited the canal four months earlier on a tour of the US.) In New York, the governor ceremonially poured a keg of water from Lake Erie into the Atlantic. The parade that followed stretched more than a mile and a half, the largest in America up to that time. Some in attendance had been at an 1815 celebration of the defeat of Napoleon, but this spectacle “so far transcended” that one “as scarcely to admit of a comparison.”

When the first transatlantic telegraph cable was laid in 1858, the celebrations “bordered on hysteria”:

There were hundred-gun salutes in Boston and New York; flags flew from public buildings; church bells rang. There were fireworks, parades, and special church services. Torch-bearing revelers in New York got so carried away that City Hall was accidentally set on fire and narrowly escaped destruction. …

Tiffany’s, the New York jewelers, bought the remainder of the cable, cut it into four-inch pieces, and sold them as souvenirs. Pieces of spare cable were also made into commemorative umbrella handles, canes, and watch fobs.3

The transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, creating the first high-speed transportation link between the East and West coasts, and turning a hazardous six-month journey by ship or wagon into a comfortable seven-day ride by rail. It, too, was called the “Eight Wonder of the World” (evidently there was no official List of Wonders to keep the numbering straight). “The building of the road was compared to the voyage of Columbus or the landing of the Pilgrims. It was said that the road was ‘annihilating distance and almost outrunning time.’ The preacher at the Golden Spike ceremony, Dr. John Todd, called it ‘the greatest work ever attempted.’”4

The western cities, now connected to the great hubs of commerce and culture in the east, were especially jubilant:

At 5 A.M. on Saturday, a Central Pacific train pulled into Sacramento carrying celebrants from Nevada, including firemen and a brass band. … The parade was mammoth. At its height, about 11 A.M. in Sacramento, the time the organizers had been told the joining of the rails would take place, twenty-three of the CP’s locomotives, led by its first, the Governor Stanford, let loose a shriek of whistles that lasted for fifteen minutes.

In San Francisco, the parade was the biggest held to date. At 11 A.M., a fifteen-inch Parrott rifled cannon at Fort Point, guarding the south shore of the Golden Gate, fired a salute. One hundred guns followed. Then fire bells, church bells, clock towers, machine shops, streamers, foundries, the U.S. Mint let go at full blast. The din lasted for an hour.

In both cities, the celebration went on through Saturday, Sunday, and Monday.5

The rest of the country, too, was celebrating the achievement:

Across the nation, bells pealed. Even the venerable Liberty Bell in Philadelphia was rung. Then came the boom of cannons, 220 of them in San Francisco at Fort Point, a hundred in Washington D.C., countless fired off elsewhere. It was said that more cannons were fired in celebration than ever took part in the Battle of Gettysburg. Everywhere there was the shriek of fire whistles, firecrackers and fireworks, singing and prayers in churches. The Tabernacle in Salt Lake City was packed to capacity, with an astonishing seven thousand people. In New Orleans, Richmond, Atlanta, and throughout the old Confederacy, there were celebrations. Chicago had a parade that was its biggest of the century—seven miles long, with tens of thousands of people participating, cheering, watching.6

In 1909, the Wright brothers returned from a tour of Europe, where they had been demonstrating their airplane.7 They were greeted as heroes. Harbor whistles blared and reporters and photographers mobbed them when they arrived in New York; back home in Dayton, Ohio, they were greeted by cannons, factory whistles, cheering crowds, and children waving flags. President Taft invited them to the White House and presented them with gold medals for their “great step in human discovery.”

A “gigantic” two-day celebration was planned in Dayton. A massive parade portrayed the history of the region from the earliest times, culminating in a float titled “All the World Paying Homage to the United States, the Wright Brothers, and the Aeroplane”; the procession stretched two miles.

On Main Street a “Court of Honor” was being created reaching from Third Street to the river, white columns lining both sides of the street and strung with colored lights. … Soldiers, sailors, and the Fire Department would march, bands play. Some 2,500 schoolchildren dressed in red, white, and blue would be arranged as a “living-flag” on the Fair Grounds grandstand and sing “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The Wrights were presented with the keys to the city, given “laudatory speeches in abundance,” and were said to have shaken hands with more than five thousand people, until only “the instinct of self preservation compelled them to cease.”

The Dayton Daily News ran an editorial at the time of the event, stating:

It is a wonderful lesson—this celebration. It comes at an auspicious time. The old world was getting tired, it seemed, and needed help to whip it into action. There was beginning a great deal of talk about man’s no longer having the opportunities he once had of achieving greatness. Too many people were beginning to believe that all of the world’s problems had been solved. … Money was beginning to tell in the affairs of men, and some were wondering whether a poor boy might work for himself a place in commerce or industry or science.

This celebration throws all such idle talk to the winds. It crowns anew the efforts of mankind. It crushes for another hundred years the suspicion that all of the secrets of nature have been solved or that the avenues of hope have been closed to those who would win new worlds.

It was an era in which such optimism was expressed unabashedly and unironically. Years earlier, on January 1, 1901, the New York World ran an editorial stating that they were “optimistic enough to believe that the twentieth century … will meet and overcome all perils and prove to be the best this steadily improving planet has ever seen.”8

It was an era in which inventors such as the Wrights were lionized with medals, parades, statues. Samuel Morse, known as “father of the telegraph,” had “honors heaped upon him by the nations of Europe”:9

He was made a chevalier of the Legion of Honor by Napoleon III; he was awarded gold medals for scientific merit by Prussia and Austria; he had further medals bestowed upon him by Queen Isabella of Spain, the king of Portugal, the king of Denmark, the king of Italy; and the sultan of Turkey presented him with a diamond-encrusted Order of Glory, the ‘‘Nishan Iftichar.’’ He was also made an honorary member of numerous scientific, artistic, and academic institutions, including the Academy of Industry in Paris, the Historical Institute of France, and, strangely, the Archaeological Society of Belgium.

In 1871, a bronze statue was made of Morse and “unveiled in Central Park amid cheering crowds, speeches, and the strains of a specially composed ‘Morse Telegraph March.’” It had been funded not by one wealthy backer but by donations sent in from telegraph operators all over the country. A “huge banquet was held… followed by numerous adulatory speeches”:

The telegraph and its inventor were praised for uniting the peoples of the world, promoting world peace, and revolutionizing commerce. The telegraph was said to have ‘‘widened the range of human thought’’; it was credited with improving the standard of journalism and literature; it was described as ‘‘the greatest instrument of power over earth which the ages of human history have revealed.’’

Morse was called a ‘‘true genius’’ and ‘‘America’s greatest inventor,’’ and “congratulatory messages flooded in over the telegraph network from all corners of the United States and the rest of the world: from Havana, from Hong Kong, from India, from Singapore, and from Europe.”

Another inventor who was memorialized with a statue was James Watt, famous improver of the steam engine. The meeting in 1824 to start a fund for this monument, according to a contemporary report in The Chemist, was “called by some of the first men of the land”; attendees included the First Lord of the Treasury, the Secretary of State, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, two earls, several MPs, Humphrey Davy, Charles Babbage, and Josiah Wedgwood II.10 The report said the monument would be “a memorial of his stupendous genius, and of our gratitude to that Power which made him the instrument of bestowing almost immeasurable benefits on the whole human race.” The statue was placed in Westminster Abbey with an epitaph that praised Watt for having “enlarged the resources of his Country, increased the power of Man, and rose to an eminent place among the most illustrious followers of science and the real benefactors of the World.” It said that the monument had been raised to show “that mankind have learned to know those who best deserve their gratitude.”11

Who, exactly, best deserved mankind’s gratitude? The Chemist stressed that it was not that common subject of monuments, the warrior, whose victories are destructive ones; rather it was men like Watt:

His were the conquests of mind over matter; they cost no tears, shed no blood, desolated no lands, made no widows nor orphans, but merely multiplied conveniences, abridged our toils, and added to our comforts and our power. … Henceforth men will perceive the folly of encouraging the shedding of human blood; will recognise the wisdom of uniting glory with usefulness; and will only erect monuments to those in whose labours there is no alloy of misery and mischief.

A similar contrast was made around this time by Samuel Smiles, the author who in this era invented a new genre: industrial biography. In the introduction to one of his books, he quoted a “distinguished living mechanic”—that is, an engineer—as having said to him:

Kings, warriors, and statesmen have heretofore monopolized not only the pages of history, but almost those of biography. Surely some niche ought to be found for the Mechanic, without whose skill and labour society, as it is, could not exist. I do not begrudge destructive heroes their fame, but the constructive ones ought not to be forgotten; and there IS a heroism of skill and toil belonging to the latter class, worthy of as grateful record,—less perilous and romantic, it may be, than that of the other, but not less full of the results of human energy, bravery, and character.12

The pinnacle of the inventor as popular hero was Thomas Edison, “the Wizard of Menlo Park.” In 1879, when he unveiled his electric light, the New York Herald ran “a full-page story headlined EDISON’S LIGHT—THE GREAT INVENTOR’S TRIUMPH IN ELECTRIC ILLUMINATION—A SCRAP OF PAPER—IT MAKES A LIGHT, WITHOUT GAS OR FLAME, CHEAPER THAN OIL—SUCCESS IN A COTTON THREAD.”13

Each subsequent afternoon and evening, flocks of electricity sightseers crowded off specially scheduled Pennsylvania Railroad trains or pulled up in the crudest of farm wagons and the most luxurious of broughams, carriages equipped with coachmen and gleaming pairs. There, as the freezing December evening enveloped the snow-clad Jersey countryside, and clouds scudded across the black night sky, the visitors would head through the dark toward the bright laboratory, there to push through and gaze in awe at the magical display. The official public unveiling was December 31, 1879, New Year’s Eve. And that evening, as the 1870s became the 1880s, three thousand people poured in to Menlo Park, ignoring the stormy weather, to see the miracle of incandescence.

Edison had continual visitors, including at one point the famous French actress Sarah Bernhardt, who “jumped all over the machinery” and “wanted to know everything” about what she saw in the lab. “When the great inventor flashed the hundreds of outdoor lights on and off in the pitch dark of the early morning, on and off, on and off, she clapped with pure Gallic delight. … ‘C’est grand, c’est magnifique!’ she exclaimed in that world-famous voice.”

The march of progress not only amazed the public, it inspired artists. As one historian put it, in the late 1700s at least,

industry was still romantic and factories still regarded as the harbingers of a better future—artists painted them, scientists eulogized them, poets were inspired by them. … Paul Sandby saw nothing incongruous in painting a coalmine; Wright of Derby thought Arkwright's mill by moonlight a subject well worthy of his brush; and Erasmus Darwin trumpeted his approval of Etruria in many a ponderous couplet.14

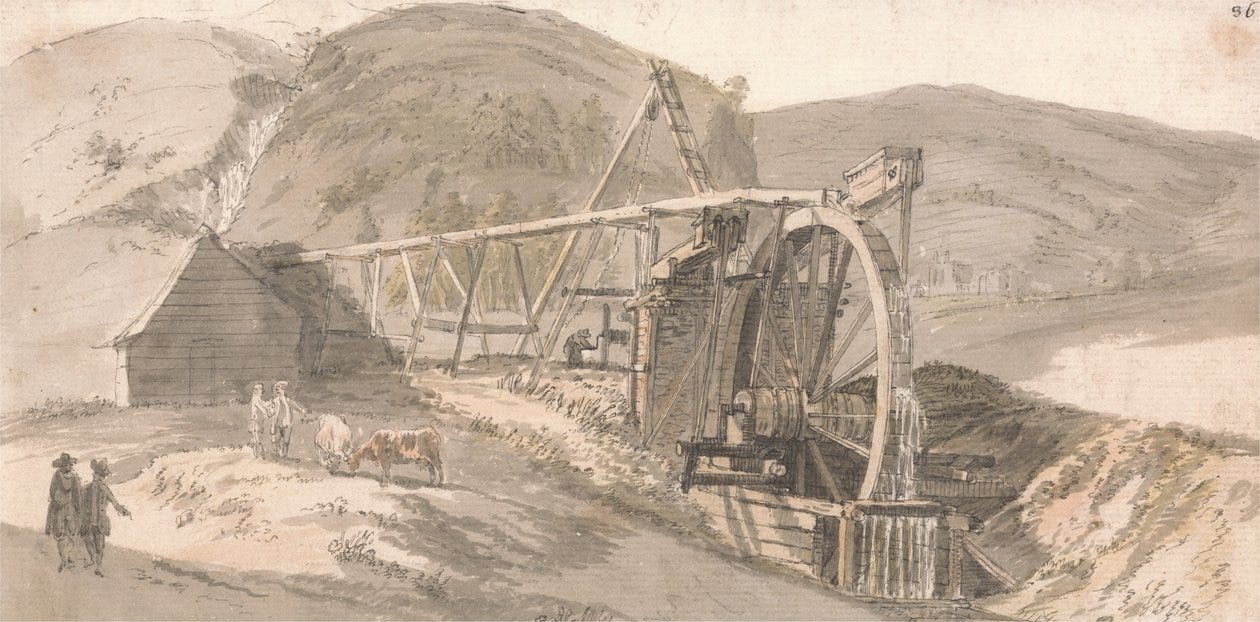

Imagine an artist painting an iron forge, or worse a lead mine. What do you envision? Something dark, foreboding, malevolent? Sandby depicted them as gentle structures that integrate harmoniously with their natural surroundings and co-exist peacefully with people and animals:

Joseph Wright took the same approach to painting cotton mills—contra Blake, dark and Satanic they are not:

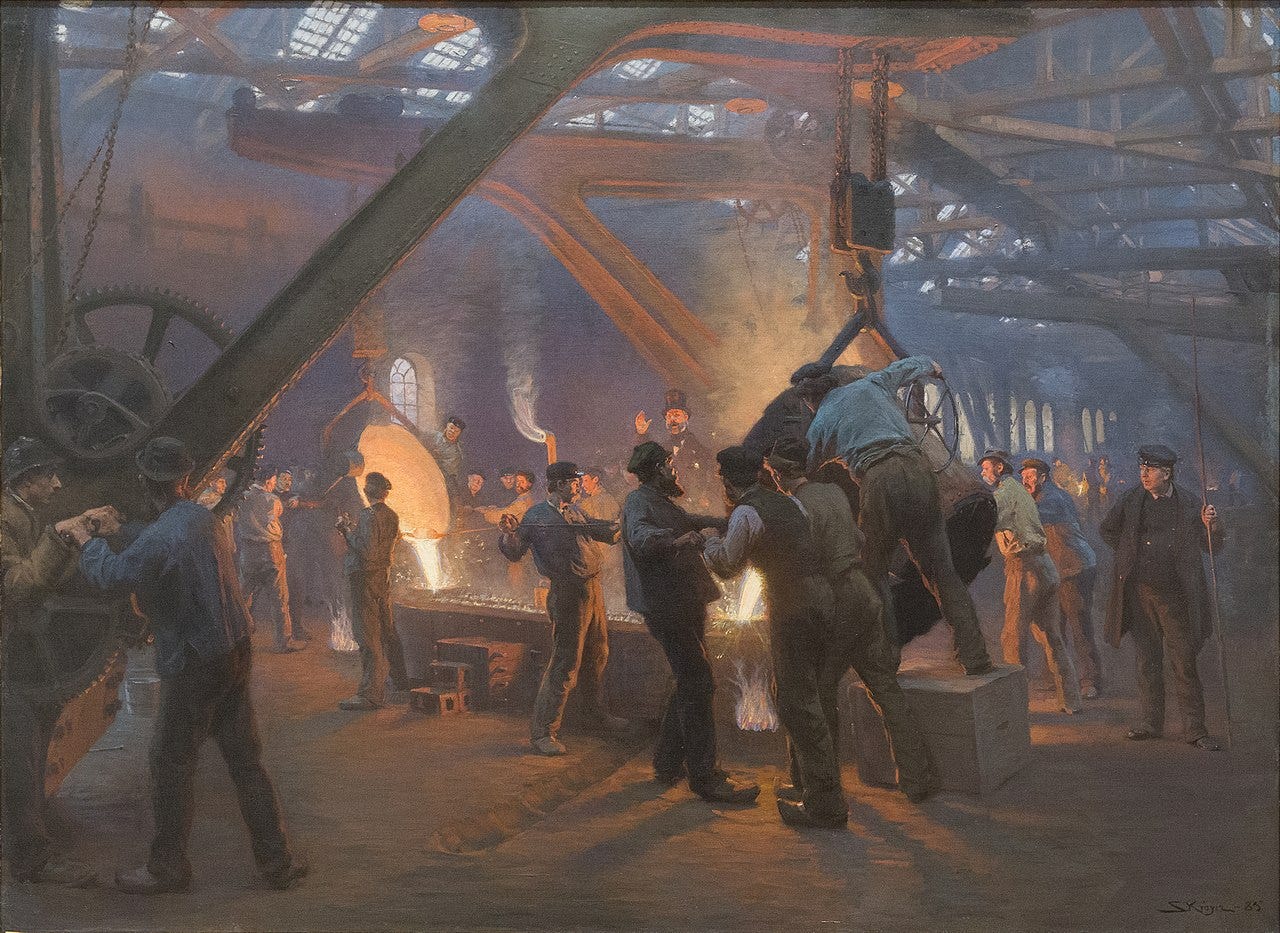

Positive depictions of the industrial continued through the 19th century. Here’s an 1885 painting of an iron foundry, by a Danish artist. The molten metal lights up the scene but does not scorch the men; the foundry and the workers are not dirty; the men are calm and in control:15

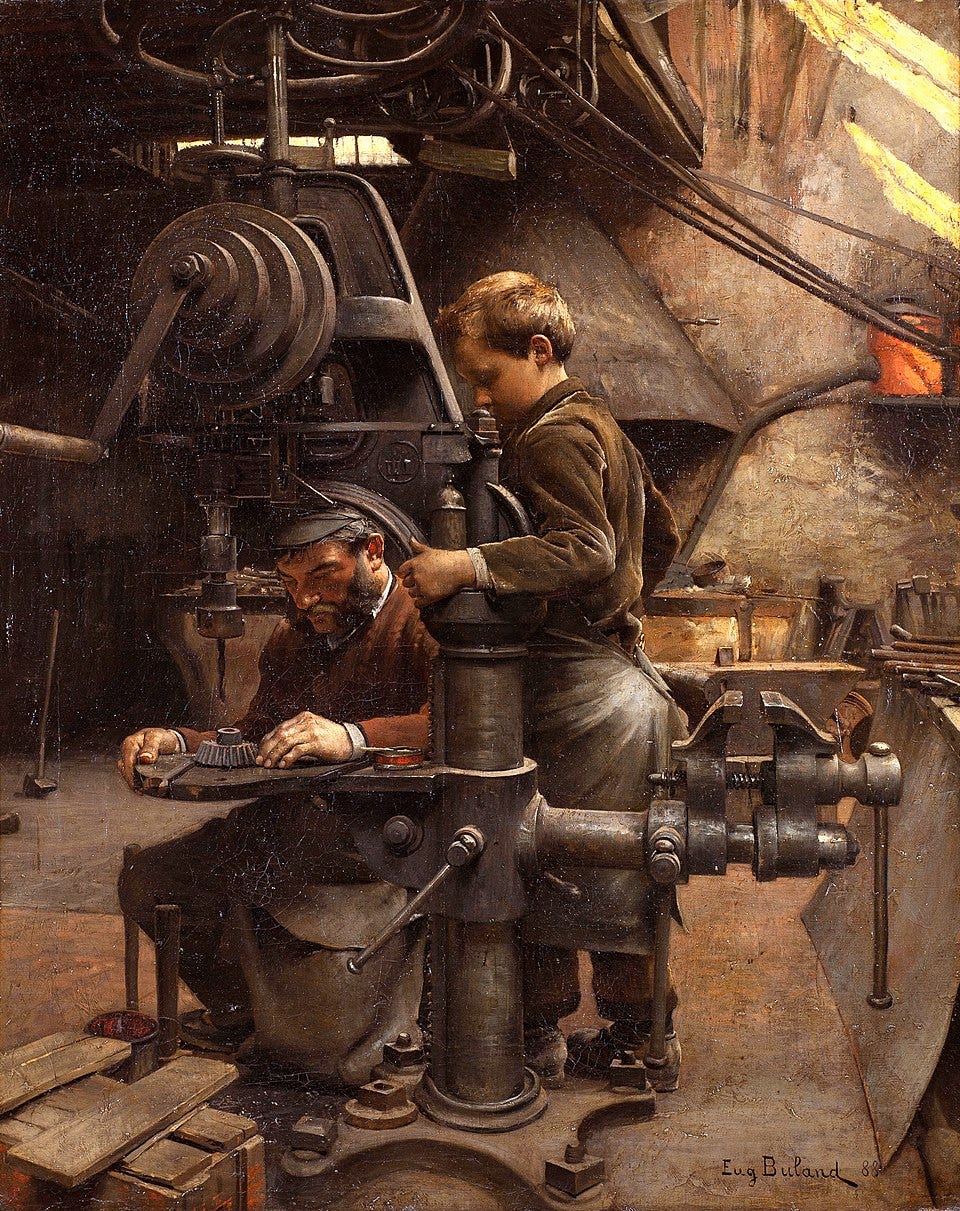

Or take this depiction of a workshop, by a French painter, 1888. The room is clean and well-lit, the machines are human-scale. The master and the apprentice are intent on their work; one can imagine a paternal affection between them:

Poets, too, were inspired by progress and optimistic for the future. Walt Whitman, perceiving that the world was being connected by railroads, canals, and telegraph cables, again likened these achievements to the wonders of the world:

Singing the great achievements of the present,

Singing the strong light works of engineers,

Our modern wonders, (the antique ponderous Seven outvied,)

In the Old World the east the Suez canal,

The New by its mighty railroad spann’d,

The seas inlaid with eloquent gentle wires…Lo, soul, seest thou not God’s purpose from the first?

The earth to be spann’d, connected by network,

The races, neighbors, to marry and be given in marriage,

The oceans to be cross’d, the distant brought near,

The lands to be welded together.A worship new I sing,

You captains, voyagers, explorers, yours,

You engineers, you architects, machinists, yours…16

Whitman describes the Suez canal with its “procession of steamships,” “the workmen gather’d” and the “gigantic dredging machines”; and “the Pacific Railroad, surmounting every barrier,” with “the locomotives rushing and roaring, and the shrill steam-whistle” whose “echoes reverberate through the grandest scenery in the world” (again we see industrial infrastructure portrayed as existing in harmony with the natural environment). He puts the accomplishment in grand historical context, as the culmination of a dream held by sailors and explorers for centuries, and extols it as “the marriage of continents, climates and oceans!” Whitman’s ultimate focus is spiritual: the highest purpose he sees for these technological accomplishments is not “trade or transportation only,” but to connect us to the past, to tradition, to ancient wisdom, and to God; much of the poem is devoted to the religious journey he anticipates for the soul. But it is significant that he sees science and technology supporting rather than degrading the soul, and the scientists, “noble inventors,” and “great captains and engineers” all preparing the way for the poet.

In 1871, Whitman was also commissioned to write a poem for an industrial exposition.17 The resulting “Song of the Exposition” extols “the spirit of invention everywhere,” likens the “joyous clank” of blacksmiths’ sledges to a “tumult of laughter,” and praises “[s]team-power, the great express lines, gas, petroleum” as “triumphs of our time,” again elevated over the ancient wonders.18

Tennyson’s “Locksley Hall” is written in the voice of a scorned lover who, at one point, wishes he could escape his sorrow by contemplating the wondrous age he lives in and the exciting prospects for the future, which in his youth made him feel “wild pulsation.” He seems, in 1835, to be prophesying air travel and airborne trade:

For I dipt into the future, far as human eye could see,

Saw the Vision of the world, and all the wonder that would be;

Saw the heavens fill with commerce, argosies of magic sails,

Pilots of the purple twilight dropping down with costly bales…19

(Famously, he also foresees the horrors of airborne warfare, but hopes that eventually there will be world union and peace between nations.)

Byron, in Don Juan, praises Newton for his discoveries and his method, which he calls:

A thing to counterbalance human woes:

For ever since immortal man hath glow'd

With all kinds of mechanics, and full soon

Steam-engines will conduct him to the moon.20

An acquaintance of Byron’s wrote that in 1822, after receiving reports of experiments with air travel by balloon, he asked “Who would not wish to have been born two or three centuries later? … Where shall we set bounds to the power of steam? … We are at present in the infancy of science.” Byron even imagined that in the far future, if a comet threatened the Earth, we might use mechanical power to “tear rocks from their foundations … and hurl mountains, as the giants are said to have done, against the flaming mass.”21

Rudyard Kipling wrote a long ballad, “McAndrew’s Hymn,” in the voice of a Scottish engineer on a passenger steamship. When a snooty first-class passenger complains to the engineer that steam power spoils the romance of sailing, McAndrew laments that poets have spent so many words on love and have ignored the engine, praying “Lord, send a man like Robbie Burns to sing the Song o’ Steam!” He calls the engine an “orchestra sublime,” and lovingly describes the harmony of the crank-throws, feed-pump, and link-head, with every part “singin’ like the Mornin’ Stars for joy that they are made.” To him, the engine represents a moral lesson: “Law, Order, Duty an’ Restraint, Obedience, Discipline!”—and he wonders whether perhaps, when the machine was forged, it was given a soul.22

In the pre-WW1 era, contrary to the fears that would arise decades later, there was outright pride in the growth of the population. In 1890, the US completed a census, and the nation eagerly awaited the result. However, the census director’s announcement “that the population of this great republic was only 62,622,250 sent into spasms of indignation a great many people who had made up their minds that the dignity of the republic could only be supported on a total of 75,000,000.” The news sent up a “howl” of “frantic disappointment.”23 The “indignation” was such that many people blamed the automatic tabulating machines, in use for the first time, for “slip shod work” that had “spoiled the census.”24 Americans were proud of being the fastest-growing country: a large and growing nation was a healthy nation, prosperous and secure.

As there was pride in growth, there was also pride in rebuilding after disaster. In 1871, when a historic fire devastated Chicago, no sooner had the blaze gotten under control than the Tribune ran an editorial headlined, “CHEER UP,” which asserted that “the people of this once beautiful city have resolved that CHICAGO SHALL RISE AGAIN. … As there has never been such a calamity, so has there never been such cheerful fortitude in the face of desolation and ruin.”25 Already, it boasted, some rebuilding contracts had been made, and the debris was to be cleared away as soon as the charred material was no longer too hot to touch. San Francisco showed the same spirit in response to the 1906 earthquake and fires; the 1915 Pan-Pacific International Exposition was in part a chance to show off how quickly and how far the city had bounced back.26

In this era, human works were not only seen to blend harmoniously with nature—they were seen as an improvement on nature. One of the orators at the Brooklyn Bridge opening spoke of the astounding transformation that had taken place in New York since its “primeval” state two hundred years prior, when it was undeveloped:

In the place of stillness and solitude, the footsteps of these millions of human beings; instead of the smooth waters “unvexed by any keel,” highways of commerce ablaze with the flags of all the nations; and where once was the green monotony of forested hills, the piled and towering splendors of a vast metropolis, the countless homes of industry, the echoing marts of trade, the gorgeous palaces of luxury, the silent and steadfast spires of worship!27

To this view, untouched nature is a “green monotony”; a built-up city is a “towering splendor.”

In the 1920s, a German engineer, Franz Westermann, made a pilgrimage to the US to see the American manufacturing system, which was then the envy of the world. The highlight of his trip was the Ford factory complex at Highland Park in Detroit. After seeing it:

Westermann wrote that he had always been moved, like so many of his countrymen, by the beauties and romance of nature. He had seen the shimmering surface of woodland lakes on nights of the full moon; he had felt the power of the endless ocean while standing on the tossing deck of a steamer in a storm; and he had been deeply moved by the sight of snow-covered Alpine peaks and dark mysterious valleys. Yet “the most powerful and memorable experience of my life came from the visit to the Ford plants, where the hand of man had created in a short time a gigantic production complex, which not only through its size and technical characteristics made a staggering impression, but also filled the viewer with the powerful organizing spirit of its creators.” At every turn a new machinescape, “a Bacchanal of work,” stimulated the engineer.28

“Natural” was not automatically good, and “artificial” or “synthetic” actually had positive connotations. Virginia Postrel reports that an 1897 newspaper article anticipating the coming of artificial ice looked forward to the day when “nature will be driven from the commercial ice business, and the inventive genius of man will have scored another improvement over his clumsy and antiquated ancestor.” Despite a backlash from incumbents, who tried to claim that natural ice was superior, artificial ice was generally seen as cleaner and healthier; another newspaper reported that “a dutiful mother will have nothing but pure ice for her children.”29 When DuPont held a “Wonder World of Chemistry” exhibit at the Texas Centennial in 1936, one woman gushed: “Now everything is synthetic,” and found it “wonderful how du Pont is improving on nature.”30 (Other visitors were skeptical, but mostly “the elderly or less sophisticated.”)

Marketers of the day found the public receptive to this message. “Wonder World of Chemistry” was also the title of a DuPont promotional film, which opened with a title card stating: “The story of progress is the story of the search for ‘Better Things for Better Living—Through Chemistry.’”31 The film unabashedly showed off insecticides, gunpowder, and dynamite—including several explosions for the purposes of mining, construction, or clearing trees away for farmland. (The only thing they didn’t want to show was munitions: DuPont was trying to escape a reputation as a “merchant of death” from WW1.) In 1942, the Bakelite Corporation made a similar film titled “The Fourth Kingdom” which proclaimed that the three natural kingdoms—animal, vegetable, and mineral—had been found “insufficient” by the modern world, which “has turned elsewhere to fulfill its needs—turned to a fourth kingdom, a kingdom of scientific research, a new domain of man’s own creation.”32 One historian describes this as marking “a victory of synthesis over extraction, of the artificial over the natural.”33

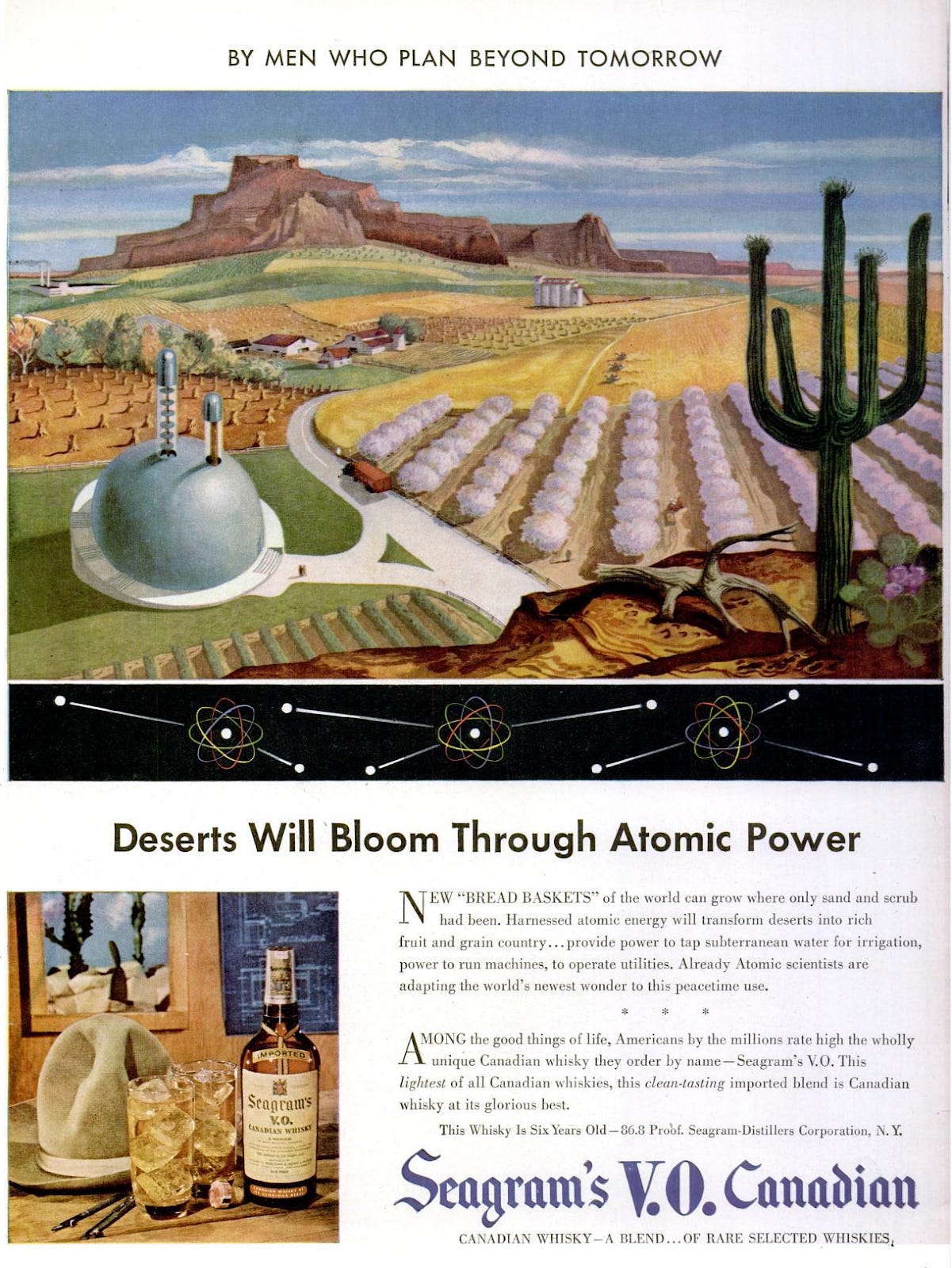

In the 1940s, Seagram’s ran a campaign for its V.O. Canadian whisky in LIFE magazine with the theme: “Men Who Plan Beyond Tomorrow.” The ads featured illustrations of then-futuristic technologies, including moving sidewalks, office computers, wireless phones, video calling, 3D movies, power plants that captured energy from lightning, “facsimile newspapers” printed from your television, grocery and meal delivery, and desert irrigation powered by nuclear energy.34 The only apparent connection to their product was that both new technologies and 6-year aged whisky require advance planning; presumably Seagram’s also simply liked the brand association with progress. In a similar spirit, a 1959 ad in the LA Times, placed by a coalition of electric companies, touted the potential for ultrasound dishwashers, automatic bed-makers, and the ability “to dial a library book, a lecture or a classroom demonstration right into your home.” The ad referred without explanation or justification to “tomorrow’s higher standard of living,” and was illustrated with a picture of a flying car.

The greatest expression of the spirit of progress was the series of grand techno-industrial exhibitions that came to be known as the World’s Fair. Each fair was an enormous event, sprawled out across hundreds of acres, with dozens or hundreds of buildings constructed to house exhibits that showed off both existing technologies and visions of the future. A World’s Fair would typically run for about six months and receive tens of millions of visitors. The tradition began in London with the Great Exhibition of 1851, which built a “crystal palace” of iron and glass to exhibit industrial technologies and products from around the world.35 The Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 featured Alexander Graham Bell’s new telephone.36 The 1889 Exposition Universelle gave Paris its Eiffel Tower.37 The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago showed off electric lighting powered by alternating current.38 The 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco was a celebration of the completion of the Panama Canal, called the “Thirteenth Labor of Hercules”; it was marketed as “a complete panorama of human achievement. … Its sole aim is to show the latest development in human progress.”39 Chicago 1933 used the tagline “A Century of Progress”; New York 1939 used “The World of Tomorrow.”40 Visitors left the 1939 fair sporting buttons that proudly proclaimed: “I Have Seen the Future.”41 For the 1964 fair in Flushing Meadows, NY, Disney developed an attraction called the Carousel of Progress, for which the Sherman Brothers (songwriters of Mary Poppins and The Jungle Book) wrote a song: “There’s a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow.”42

Other celebrations of progress also continued well into the 20th century. In the 1920s and ‘30s, a common spectacle in New York was the ticker tape parade celebrating a heroic aviator—not only Charles Lindbergh (1927), Amelia Earhart (1928 and 1932) and Howard Hughes (1938), but dozens of other forgotten names for achievements such as flights across the Atlantic, over the North Pole, or around the world. In the 1960s the parades were held for astronauts, including Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, Michael Collins, John Glenn, Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, and many less well-known names.43 The Apollo 11 crew went on a world tour to receive such celebrations and honors.44

In 1955, the polio vaccine was announced. Polio had terrified the nation: it struck in major epidemic waves every summer, with young children most vulnerable; the disease killed many of them and left many more paralyzed for life. The vaccine was received as a godsend, and Jonas Salk, who led its development, was hailed as a hero and savior. According to one history:

A contagion of love swept the world. People observed moments of silence, rang bells, honked horns, blew factory whistles, fired salutes, kept their traffic lights red in brief periods of tribute, took the rest of the day off, closed their schools or convoked fervid assemblies therein, drank toasts, hugged children, attended church, smiled at strangers, forgave enemies. …

The ardent people named schools, streets, hospitals, and newborn infants after him. They sent him checks, cash, money orders, stamps, scrolls, certificates, pressed flowers, snapshots, candy, baked goods, religious medals, rabbits’ feet and other talismans, and uncounted thousands of letters and telegrams, both individual and round-robin, describing their heartfelt gratitude and admiration. They offered him free automobiles, agricultural equipment, clothing, vacations, lucrative jobs in government and industry, and several hundred opportunities to get rich quick. Their legislatures and parliaments passed resolutions, and their heads of state issued proclamations. Their universities tendered honorary degrees. …

Salk awakened that morning as a moderately prominent research professor on the faculty of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. He ended the day as the most beloved medical scientist on earth. Worshipful humanity had borne him far beyond mere fame and had enthroned him among the immortals.45

Another historian writes:

Gifts and honors poured in from a grateful nation. Philadelphia awarded Salk its Poor Richard Medal for distinguished service to humanity. Mutual of Omaha gave him its Criss Award, along with a $10,000 check, for his contribution to public health. The University of Pittsburgh was swamped with thank-you notes and “donations” addressed to Dr. Salk. His lab was “knee-deep in mail,” a staffer recalled. … Elementary schools sent giant posters—WE LOVE YOU DR. SALK—signed by the entire student body. Winnipeg, Canada, site of a major polio epidemic in 1953, sent a 208-foot telegram of congratulation adorned with each survivor’s name. A town in the Texas panhandle bought him two heartfelt, if comically inappropriate, gifts: a plow and a fully equipped Oldsmobile 98. (Salk gave the plow to an orphanage and had the car sold so the town could buy more polio vaccine.) A new Cadillac arrived and was donated to charity. Colleges begged him to accept their honorary degrees. Newsweek lauded “A Quiet Young Man’s Magnificent Victory,” insisting that Salk’s name was now “as secure a word in the medical dictionary as Jenner, Pasteur, Schick, and Lister.” … The stories that day spoke of mothers weeping, doctors cheering, politicians toasting God and Jonas Salk.46

Warner Brothers, Columbia, and Twentieth Century Fox fought for the rights to Salk’s life story, with rumors of Marlon Brando as the lead (Salk turned them all down). He was awarded a Congressional Gold Medal, only the second medical researcher to ever receive one. He was nominated for the Nobel prize. He was received at the White House, in a special ceremony at the Rose Garden. President Eisenhower was visibly moved, telling Salk in a trembling voice, “I have no words to thank you. I am very, very happy.”47

Salk had saved the lives of countless children, and the public made him into a hero. But there was a writer in this era who saw all such work as heroic—science, invention, even entrepreneurship. That writer was Ayn Rand, and the pantheon of heroes in her 1957 novel Atlas Shrugged included researchers, engineers, and executives in industries such as railroads, oil, copper, steel, and banking. They were intelligent, competent, ruthlessly logical, and above all, they could get things done. The plot is driven in part by their inventions: a new metallic alloy, a method of extracting oil from shale (presaging fracking), a new form of energy production from “static electricity from the atmosphere.” Scenes of industrial achievement are described with romance and glamour: metallurgical research, the first run of a train on a new railroad line, a break-out at a steel furnace that forces workers to close the hole by throwing chunks of fire clay into it by hand. Corporate logos are likened to the coats of arms of noble houses; a motor is described as “a moral code cast in steel.”48 (Rand, like Kipling, saw both poetry and moral meaning in the engine.)

The inventors and industrialists of Atlas Shrugged keep the world running and carry the rest of humanity on their shoulders; their work is portrayed as a grand quest to use reason in the service of human life. Indeed, a core tenet of Rand’s philosophy was that “productive achievement” is mankind’s “noblest activity.”49 (She did not, however, give scientists or CEOs unconditional adoration: her worst villains in the novel include crony businessmen who profit from protectionism, and a physicist whose gravest sin is to blindly serve the state, which uses his discoveries to build a terrible weapon.)

Rand wrote, however, at a time when ideas like these were already out of favor—in part, she was attempting to revive them, explicitly thinking of herself as a bridge from the pre-WW1 culture of confidence and optimism to her own time.50 But by the 1970s, the zeitgeist had dramatically changed: now there were fears of overpopulation, pollution, and the “limits to growth”; constant anxiety from the threat of nuclear war; and deep distrust of the institutions of science, industry, media, and government.

What had happened?

Next: Chapter 9, part 2

For more about The Techno-Humanist Manifesto, including the table of contents, see the announcement. For full citations, see the bibliography.

The description of the celebration taken from McCullough, The Great Bridge, 477–98.

The description of the Erie Canal celebrations taken from Bernstein, Wedding of the Waters, 315–26.

Standage, The Victorian Internet, 80–81.

Ambrose, Nothing Like It in the World, 356.

Ambrose, 361–2.

Ambrose, 366.

The description of the Wright brothers celebration, including the passage from the Dayton Daily News, taken from McCullough, The Wright Brothers, 227–33.

Quoted in Almond, Progress and Its Discontents, Foreword, x.

The description of the celebrations and honors for Morse taken from Standage, Victorian Internet, 181–7.

The Chemist. The attendees are confirmed by the proceedings.

“James Watt.”

Smiles, Industrial Biography: Iron Workers and Tool Makers, Preface.

The description of how Edison’s electric light was received taken from Jonnes, Empires of Light, 82–92.

McKendrick, “Josiah Wedgwood and Factory Discipline”.

My thanks to sculptress and art historian Sandra Shaw for bringing this and the subsequent painting to my attention during a lecture, and for helping me to interpret them.

Whitman, “Passage to India.”

Wolfe, “Song of the Exposition: About.”

Whitman, “Song of the Exposition.”

Tennyson, “Locksley Hall.”

Byron, Don Juan, Canto X. My thanks to Fawaz Al-Matrouk for bringing this to my attention.

Medwin, Journal of the Conversations of Lord Byron, 129-130.

Kipling, “McAndrew’s Hymn.”

University of Michigan, Electrical Engineer, 522.

Campbell-Kelly, Computer: A History of the Information Machine, 24.

Chicago Tribune, Oct. 11, 1871, “Cheer Up—Chicago Shall Rise Again.”

Kingsley et al., Opening Ceremonies of the New York and Brooklyn Bridge, 45.

Hughes, American Genesis, 292.

Postrel, “Artificial Flavoring”; Anslow, “The War on Artificial Ice.”

Meikle, American Plastic, 135.

Meikle, American Plastic, 114.

McCracken, “Men Who Plan Beyond Tomorrow!”. The ideas mentioned appeared in LIFE magazine on Feb 22 and Jun 14, 1943; Mar 20, Apr 17, Oct 2, and Nov 20, 1944; Mar 12 and Oct 29, 1945; Feb 18, 1946; and May 12 and Jun 16, 1947.

Jason Crawford (@jasoncrawford), “A complete panorama of human achievement …,” X.

Mullen, “Walt’s World Fair.”

Alliance for Downtown New York, “History of New York City’s Ticker Tape Parades.”

Carter, Breakthrough, 1–2.

Oshinksy, Polio, 216.

Oshinksy, 216.

Rand, Atlas Shrugged, 230.

Rand, Atlas Shrugged, “About the Author,” 1070.

Rand, The Romantic Manifesto, vi–viii.

A grand and delightful read! Thanks for all your research!

What happened, indeed. I felt very similarly after reading Devil in the White City centered on the 1893 Chicago World's Fair; earnest pomp, circumstance and celebration for both invention and civic pride seem almost foreign and jingoistic today. Great read, excited for part 2!